Why we need to talk about postnatal depression in men

- Published

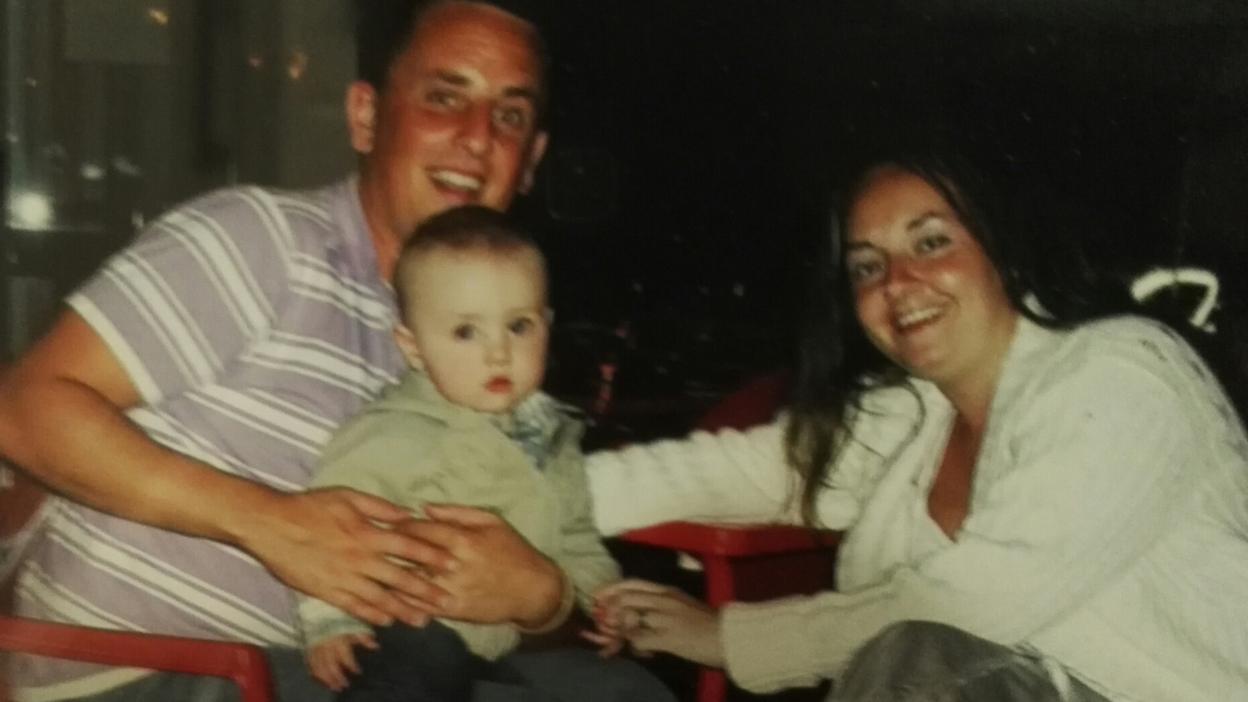

I thought fatherhood would turn me into a superhero. Instead, I felt like a super-failure.

Today, 18 June, marks . Here, our writer talks about his experience of developing postnatal depression after the birth of his first child.

Like most people, I'd have probably scoffed at the concept of postnatal depression in men. Until the events of 26 May 2009, anyway.

That’s when what should have been the happiest day of my life turned into a bit of a nightmare.

At around 7am that morning, after a tortuous, three-day labour, my partner, Diana, went into a terrifying, flailing seizure.

In that horrific moment, I genuinely feared Diana might die, taking our unborn child with her. With alarms screaming, Diana was rushed into an emergency C-section. For some stupid reason, I filmed it. Mistake: it was like field surgery in a war zone.

Eventually, our baby boy was pulled out, grey, and apparently lifeless. He was placed on a steel trolley, where, after two agonising minutes, he finally started breathing.

My first thought was, “Well, that wasn’t in any of the parenting books”. But my overriding emotion was one of total powerlessness.

I thought fatherhood would turn me into a superhero. Instead, I felt like a super-failure. I felt like all of this was my fault.

In the following months, I quietly fell into depression and suffered flashbacks of my son’s birth. I constantly worked late to avoid being at home, and went off sex - I’d decided that was the cause of it all.

But while Diana was (rightly) offered counselling by our care visitor – she was struggling with the baby blues – it was as if I didn’t exist. I wasn’t asked at any point how I was coping, even though this was all new to me, too.

Now, though, postnatal depression (PND) in men seems to be finally getting the attention it deserves.

It is not known exactly . It’s often mistakenly considered to be a hormonal condition, but feelings of isolation, recent stressful events, a history of mental health problems, and other unresolved issues from the past can all trigger it. And these are all things that can apply to men, too.

Last year, the landmark found that, while men were only half as likely to report symptoms of PND (one in 25 men, compared with one in 12 women),В they were almost exactly as likely to be hit by it.

One in 15 recent fathers suffered depression at some time between the third trimester of pregnancy to nine months after birth.

These men were measured on the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), a 10-item questionnaire to identify clinical depression symptoms in women, ranging from guilt, sleep disturbance, and low energy to suicidal thoughts.

The study’s author, Dr Lisa Underwood, said: “There is no routine screening for fathers before or after the birth of their children. Given the potential for paternal depression to have direct and indirect effects on children, it is important that we recognise and treat symptoms among fathers early.”

Mark Williams is a mental health campaigner from Bridgend. He suffered postnatal depression for six years after the birth of his son, Ethan, in 2004.

“I had a panic attack at Ethan’s birth, as I thought my wife was going to die,” he says. “I had nightmares, depression and suicidal thoughts. I didn't tell my wife as I didn’t want to burden her. I eventually had a breakdown.”

Mark’s partner, Michelle, who also suffered terribly from PND, feels we need to completely change the way we think about it.

“Mark suffered in silence for years. It was only when he had a breakdown that the truth came out. There needs to be a more holistic approach to perinatal mental health care," she says.

That's a sentiment shared by Dr Andrew Briggs, consultant child psychotherapist at Sussex Partnership NHS. Over the past 30 years, he has treated around 400 men who have suffered PND.

“There are as many types of male postnatal depression as there are men who suffer it,” he says. “Yet PND in men is often met with thinly-veined ridicule. It’s deeply ingrained within the cultural psyche that men should just pull themselves together."

For this reason, he thinks, “Care provision is still very mother-centric: men aren’t seen as an equal part of the family jigsaw puzzle. We’re letting men down all across the board.”

AndrГ© Tomlin, a company director from Bristol, recently emerged from a year-long bout of depression following the birth of his third child.

“My depression put a huge strain on my relationship with my wife, Leah, and I was definitely a less attentive father for a while, in the depths of my illness," he says. "Appropriate support for dads just isn't available in the same way as it is for mothers, but I was extremely lucky to have such a loving and understanding family around me.”

In the end, he says, “What worked for me was a combination of things: admitting that I needed to be rescued, letting people support me, plus exercise, antidepressants, music, and counselling.”

He adds: "What would have helped me most would have been sharing experiences with other men like me, but the support networks just weren’t in place.”

My own route to happiness began when I finally opened up to Diana four years ago. She was wonderfully supportive, and organised NHS couples counselling, which is free, and brilliant.

There were a lot of tears, and I realised I was lucky to have a child at all. I quit my job as a magazine editor to be at home more, and Sonny is now a healthy, happy seven-year-old boy.

The final piece of my jigsaw was our daughter, Dolly, who came into the world on 2 March 2014. Her birth was everything Sonny’s wasn’t: quick, natural, and, Diana assures me, (relatively) painless.

Diana says: “I wish Martin had opened up sooner. I saw that as a strength, not a weakness. By him being open, we were able to get better together. Ultimately, Dolly’s birth was a rebirth for us all.”

For information and support if you think you are experiencing postnatal depression, these organisations may be able to help.

This article was originally published on 8 May 2017.