Is world hunger a problem too great to solve?

- Published

Today is World Hunger Day. As campaigns go, IÔÇÖd expect this one to be the biggest, what with hunger being the most pressing threat to humanity and all, but thereÔÇÖs not even a wristband.

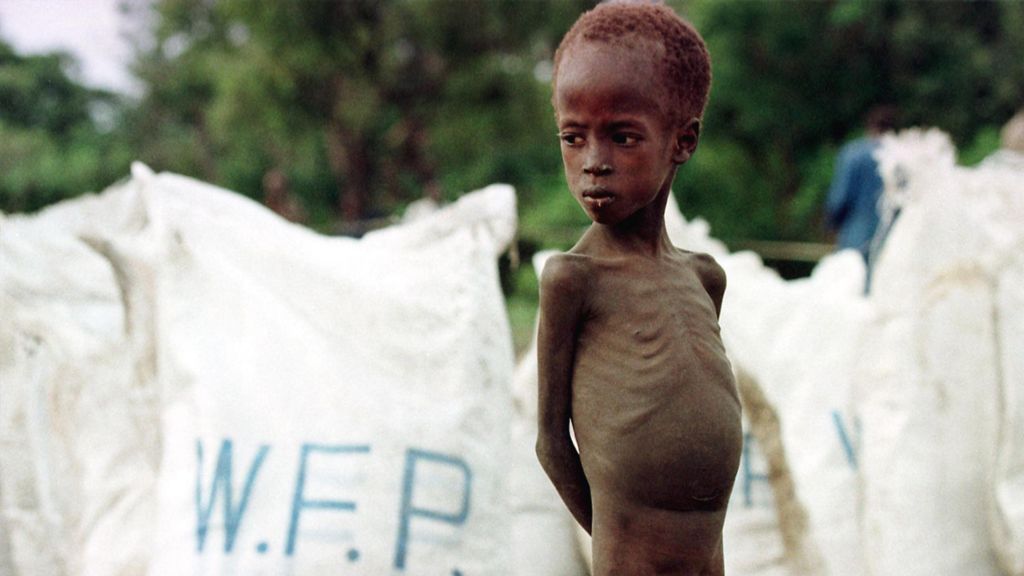

There are 795 million people on Earth who do not have enough to eat. Hunger kills more people than AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis combined. We often hear the word ÔÇÿcrisisÔÇÖ when we talk about the developing world, but with a massive 50 million people across Africa facing the worst famine since 1985 and almost all of southern Africa predicted to be┬áwithout food by Christmas, crisis is an understatement.

In 1984, when British people switched on the evening news and saw the shocking images of the Ethiopian famine, it sparked a global campaign to Feed The World. But hunger didn't end. What has happened to the way we think about, and respond to, hunger?

As the Disasters Emergency Committee warned with regard to a second South Sudanese famine: "We are very concerned... that despite some excellent news coverage of the situation, public awareness of the crisis in the UK remains very low."

Last year, I spent some time working as a nurse in South Sudan, the youngest country on Earth and already facing its second famine. All my patients had one thing in common - malnutrition. Nutrition came to be the theme of my work. The heartbreaking and frustrating thing for us was that there was no drug, no surgery and no treatment that would work without good nutrition. We couldnÔÇÖt treat wounds, disease or disability without the patient being sufficiently nourished.

In the UK, our young patients tend to recover well from illness or injury, but in South Sudan, children died because they were too weak. If, with my patients, everything relied upon nutrition, it should stand to reason that in global development, everything relies upon food security. In the humanitarian sector, there is little doubt that food security is the bedrock on which everything else depends.

The urgency of global hunger may well be understood by the public, but, according to Oscar Sarroca, former Country Director of the UN's World Food Programme, we are now overwhelmed by other factors. ÔÇ£While millions of people continue to suffer from hunger, the terrorism pandemic competes for public attention and appeals to our sense of solidarity.ÔÇØ

There is certainly a frightening sense of shock after a natural disaster or terror attack, which prompts a public reaction borne out of empathy. Ebola and Zika have both hit the headlines, perhaps because of the indiscriminate nature of disease. Is it just the case that we in the developed world arenÔÇÖt as focused on food shortages as we are on terror or disease, because we find it hard to connect with?

It isnÔÇÖt just our jaded attitude to hunger that has affected our collective response, but also the complexity of the solutions. The public could be forgiven for thinking that, after the ÔÇÿtrade not aidÔÇÖ message of the past few decades, the answer is in the hands of governments.

However, we have learned that governments can impede the path to food security. The problem is not only corruption, which is often referred to, but also unfair international practices and policies. Global financial markets, driving up the price of staplefoods like rice can also create malnutrition pandemics.

When I think about hunger I think about my patients in South Sudan. I wonder how long it will be before real, sustained, achievable food security ensures that they, and millions more like them, won't forever live with the threat of famine.