Whether you saved for months to buy your first pair of ripped jeans, or were a little flummoxed when the first miniskirts arrived, fashion will have impacted your life at some point.

Although we donÔÇÖt all stick to the latest trends as soon as they shift course, fashion should never be dismissed too quickly. In the UK alone, the fashion industry was worth ┬ú26 billion in 2016 and kept around 800,000 people in work.

And like any other business, fashion has its tales to tell. ┤¾¤¾┤½├¢ Bitesize has delved into the dressing up chest of history to find the stories behind five popular everyday items and trends.

Nylon is NOT named after New York and London

What a delicious combination. The initials of one of the USAÔÇÖs liveliest cities combined with the first syllable of the British capital. An ocean may divide them but there has long been a rumour that the creation of a synthetic fabric brought the two together in symbolic fashion, with scientists from both countries working on the formula.

ThatÔÇÖs simply not true. Nylon was created in the 1930s at AmericaÔÇÖs DuPont Chemicals. The scientist Wallace Carothers led the team working on a new polymer known as ÔÇÿfiber 6-6ÔÇÖ. Used in toothbrush bristles first, it first became available in the form of stockings in 1940. In an America still picking itself up from the Depression era, they were an affordable luxury which had queues forming outside department stores.

The name simply came from playing around with syllables and brand names, as DuPont confirmed in 1978. The original, desired, name of ÔÇÿNoRunÔÇÖ could have led to problems involving trade descriptions if the fabric did run (or unravel) in reality. Briefly ÔÇÿnuronÔÇÖ, the sound was re-jigged again to produce ÔÇÿnilonÔÇÖ and then ÔÇÿnylonÔÇÖ. More than anything, an ÔÇÿonÔÇÖ ending made it sound similar to other materials such as cotton and rayon.

The first pair of Dr Martens was made from a tyre

They may appear a symbol of Britishness, with their links to punk and student discos, but the Dr Martens boot came to these shores in a collaboration between the UK and Germany.

It all began in Munich in the aftermath of World War Two. German soldier Dr Klaus Maertens was convalescing after breaking his foot but his army boots were not ideal when it came to the required level of comfort. He set about crafting a solution. Uppers made from a soft leather were combined with air-cushioned soles - made from tyre - to provide support for Dr MaertensÔÇÖ injury. He knew there was something to his design and worked on it further, eventually setting up in business.

Dr MaertensÔÇÖ successful footwear empire grew so much that it attracted interest overseas. In 1959, the R Griggs Group bought the rights to produce the boots in the UK. The firm modified the sole, introduced the very identifiable yellow stitching and made the name the more Anglophone friendly Dr Martens, along with bringing in another name, AirWair, plus the slogan 'with bouncing soles'. The first pair went on sale in the UK on 1 April, 1960.

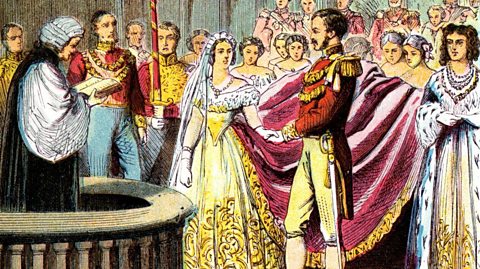

Queen Victoria introduced the white wedding dress to Britain

In 1840, Britain was whipped into the sort of frenzy we last saw with the wedding of Prince Harry and Meghan Markle as Queen Victoria prepared to marry her great love, Albert, three years into her reign.

It was an era when wedding dresses were not designed to be worn once and brides opted for various colours. If anyone did wear white, it was seen as a sign of wealth as it meant they could also afford the bill when it came to having it cleaned properly.

In VictoriaÔÇÖs case, her dress involved lots of lace, a deliberate move to promote BritainÔÇÖs own industry in the fabric, while the cream silk of the main gown was woven in LondonÔÇÖs Spitalfields. That shade was chosen deliberately as it was ideal for accentuating the lacework.

A formal request was made that no other guest, bar the bridesmaids, wore white to the ceremony, meaning that the dress, adorned with orange blossoms, stood out on the official portraits of the event. Those images appeared in newspapers and journals around the world giving a white wedding dress a royal seal of approval and increasing its popularity.

The dress wasn't then packed away for posterity. Elements of Queen Victoria's wedding outfit were re-used at other major milestones in her life. Her veil was worn at the christenings of all her children and beneath her crown on her official Diamond Jubilee photograph.

The mini skirt is not named after its length

Pinpointing the creator of 1960s fashion must-have, the mini skirt, is tricky. A handful of designers were playing around with the idea of a shorter skirt than was usually seen in everyday life during the decade, but it was Welsh fashion designer Mary Quant who put a special stamp on the concept.

Her boutique in LondonÔÇÖs KingÔÇÖs Road began selling miniskirts in 1966, but her fascination with the garment began when she was taking ballet classes a few years earlier.

Her own inspiration came from childhood dance classes, where she was captivated by a tap dancer wearing a 10-inch pleated skirt. The freedom of movement and liberation it gave the performance made it stay in Mary's mind until it became a reality years later.

People would be forgiven for thinking that a 10-inch long skirt would automatically name itself as a 'mini', but it actually comes from MaryÔÇÖs affection for another symbol of the era, the Mini Cooper car.

Her favourite make of car, Mary thought its look and youth appeal was in perfect sync with her garment and named the mini skirt in its honour. She even introduced coloured tights to accompany them. The briefer length of a mini skirt was considered inappropriate for the traditional stocking and suspender.

The Ancient Egyptian make-up craze

Archaeology was a big deal in the 1920s. Howard CarterÔÇÖs expeditions to unearth relics from beneath the Egyptian sands captivated the world and had a surprising impact on the way people looked.

At the time, make-up was still something that wasnÔÇÖt obvious. If a woman wore too much of it, her good character came into question (Queen Victoria had declared cosmetics as both 'unladylike' and 'vulgar' in the 19th Century), but that all changed when a bust of another Queen, Egypt's Nefertiti, was discovered in 1912 and, 10 years later, the tomb of King Tutankahmun.

The obvious use of eyeliner on the imagery associated with both figures caused a stir. It influenced fashion, with Ancient Egyptian designs having an impact on clothes, and also eye make-up.

The kohl pencil, used as eyeliner, suddenly became more popular than ever. Early film stars, such as the actress Clara Bow, famous for being the ÔÇÿItÔÇÖ Girl from the 1927 movie of the same name, would wear heavy make-up on screen, partly to emphasise their performances in the pre-talkie era. It wasnÔÇÖt just actresses who wore it. Charlie Chaplin and Rudolph Valentino both applied eyeliner for the cameras, although the former used it for comedic purposes as opposed to smouldering for his fans.

That chaste approach to make-up had been turned on its head in a matter of decades. Loved by beaming 1950s Hollywood stars and sullen 1980s music legends alike, to this day the eyeliner is arguably the only make-up item with the same iconic status as the red lipstick.

Can we ever really know if our clothes are sustainable?

Bitesize speaks to sustainability experts about the fashion industry, fast fashion and our shopping habits.

Gemma: fashion designer

Gemma launched her own fashion brand.

Lucy ÔÇô a fashion and make-up blogger ÔÇô helps Beulah put together an outfit on a budget for her job interview.