Dictionaries have been part of British life since at least 1604, when Robert CawdreyŌĆÖs A Table Alphabeticall was published.

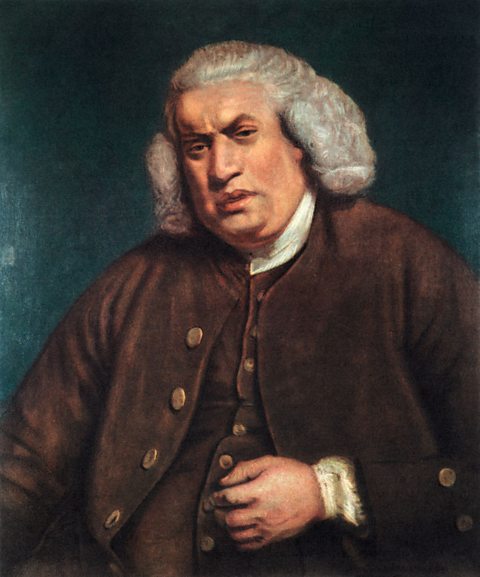

Containing around 3,000 words and their definitions, Cawdrey hoped it would encourage people to expand their vocabulary and improve their spelling. But it took just a smidge over 150 years for another dictionary to be published that, arguably, set the standard for those that followed. On 15 April 1755, Dr Samuel JohnsonŌĆÖs Dictionary of the English Language became available for the first time, containing a list of definitions across two volumes that was around 14 times greater than CawdreyŌĆÖs Table.

The Staffordshire-born writer and his team, working in a house off LondonŌĆÖs Fleet Street, took eight years to research and produce the dictionary, regarded as the most concise and complete record of English to that point.

But how does Dr JohnsonŌĆÖs dictionary compare to those we use in the 21st Century? After more than 260 years, are his methods and practices still used by todayŌĆÖs lexicographers? Bitesize put some questions to the writer and author Henry Hitchings, who has researched Dr Johnson extensively, as well as other aspects of the English language.

Difference in size and style

JohnsonŌĆÖs dictionary was considered comprehensive for the time, but its content is dwarfed by those we use today.

Henry explained: ŌĆ£The first thing you are likely to notice is that JohnsonŌĆÖs dictionary is, physically, two volumes about 18 inches tall, each weighing almost five kilograms. But it defines only 42,773 words. While that might sound like a lot, today the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) provides definitions of over 600,000.ŌĆØ

Large teams are responsible for compiling todayŌĆÖs dictionaries but even though Johnson worked with his own group of helpers, Henry says that his dictionary should be seen as a very personal piece of work.

He said: ŌĆ£He was able to inject his own character into it. This makes it a work of literature, as a reference book it has been superseded, but it is still rewarding to study or simply browse through.ŌĆØ

The entertainment value in JohnsonŌĆÖs dictionary, Henry says, can come from the way he occasionally allowed his own opinions to colour the definitions. He provided a couple of examples: ŌĆ£He [Johnson]defines ŌĆścanaryŌĆÖ as ŌĆ£an excellent singing birdŌĆØ and ŌĆśfortune-tellerŌĆÖ as ŌĆ£one who cheats common people by pretending knowledge of futurityŌĆØ.ŌĆØ

They werenŌĆÖt definitions that stood the test of time. The OED website now defines canary in more neutral terms as ŌĆśAn Old World finch native to the Canary Islands, the Azores, and Madeira, widely popular as a cage and aviary bird for its melodious songŌĆÖ. But thatŌĆÖs probably closer to JohnsonŌĆÖs original definition than ŌĆśfortune-tellerŌĆÖ is today. The current definition for that is quite simply: ŌĆ£One who tells fortunes.ŌĆØ

X marks the gap

Pick up a dictionary today (or look to its website) and words of all kinds are in there, even the sort you wouldnŌĆÖt say out loud in front of your gran.

The first buyers of JohnsonŌĆÖs dictionary would not have found any words that polite society considered rude, or rather, ones that Johnson himself thought unsavoury. There were other omissions too, but not always because they were examples of language that could make you blush.

Henry said: ŌĆ£[Johnson] also left out some words that he found during his research but wasnŌĆÖt convinced were English, including a few adopted from French, such as ŌĆśuniqueŌĆÖ and ŌĆśchampagneŌĆÖ.ŌĆØ

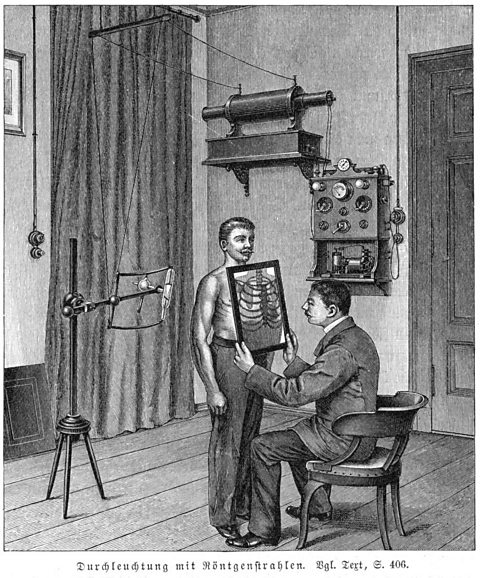

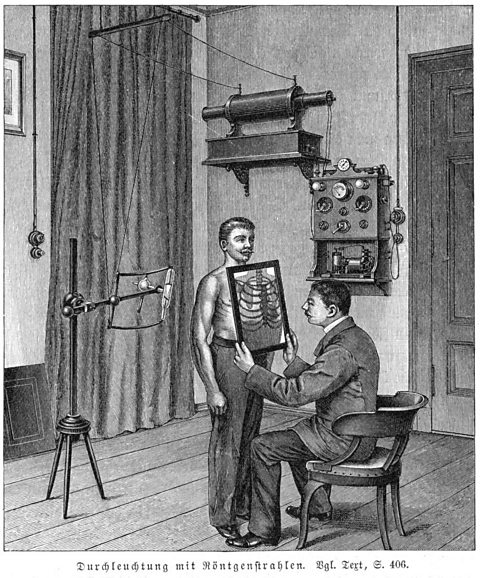

Perhaps the most noticeable omission from a 21st Century viewpoint is the complete lack of any words beginning with X. ŌĆ£But thatŌĆÖs not as weird as it sounds,ŌĆØ Henry said. ŌĆ£Most of our X words, such as ŌĆśX-rayŌĆÖ and ŌĆśxylophoneŌĆÖ, were first used after Johnson's time.ŌĆØ

Looking for words 'in the wild'

Although there are differences between JohnsonŌĆÖs dictionary and those we see today, the compiling of these two historic volumes also established practices still in use by lexicographers. That included having an inquiring mind about language use.

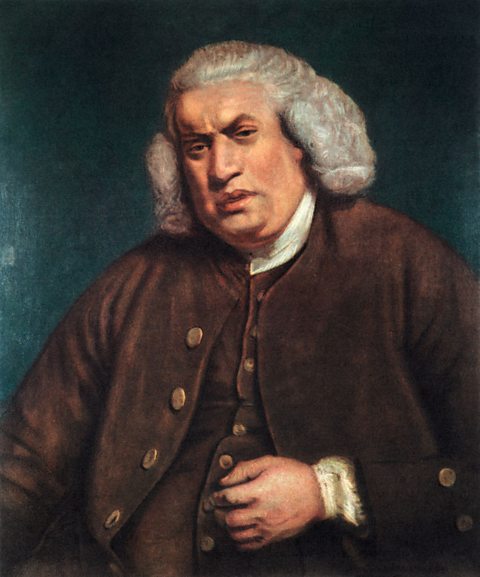

Henry said: ŌĆ£JohnsonŌĆÖs most important innovation was that he looked for words ŌĆśin the wildŌĆÖ. He believed he had to find a written source for everything; it was no good to include a word just because heŌĆÖd heard it. But his dictionary differed from previous ones because, instead of starting with a list of the words he thought he ought to define, he read as much as he could, keeping a note of all the words he encountered.

ŌĆ£In the finished dictionary, he included quotations that showed the words actually in use. The inclusion of these ŌĆśillustrative quotationsŌĆÖ was influential. The best modern dictionaries follow this practice; one reason is to provide a detailed record of how the use of a particular word has changed over time.ŌĆØ

What you've got until it's gone

Language change is constant - even if we donŌĆÖt necessarily notice it - but that does mean losing a few words from our vocabulary along the way.

There are many words in JohnsonŌĆÖs original which havenŌĆÖt survived the 250 years-plus since they were first recorded. ŌĆ£There are lots of words he recorded that we donŌĆÖt use any more,ŌĆØ said Henry. ŌĆ£I donŌĆÖt think IŌĆÖve ever seen or heard anyone call a person who empties lavatories a ŌĆ£goldfinderŌĆØ.ŌĆØ

He continued: ŌĆ£Some, perhaps, deserve revival, like ŌĆ£mouth friendŌĆØ - one who professes friendship, without intending it.ŌĆØ

The ridiculously difficult rare words quiz

These are some of the rarest words in the Oxford English Dictionary. Do you know what they mean?

Why do we keep misspelling these words?

Find out what spelling can reveal about the evolution of English.

LGBTQ+ coded languages

Explore the world of Polari and the diaries of Anne Lister (Gentleman Jack).