When posters of soap stars head-to-toe in sequins start appearing on buses, it can only mean two things: Strictly has started - or it's panto season.

Corny jokes, panto dames and fairy tales might seem a little dated, but as the festive season gets underway many families are still flocking to their local matinГ©e, giddy with excitement.

From community halls to the fanciest of theatres, our favourite pantomime characters will be waiting in the wings once again this year.

But pantomime is not the most modern of affairs, it has actually been around for over 500 years.

So, why does it never get old?

It's behind you!

The panto we know and love today – with its slapstick humour and audience participation – has its roots in Italian street theatre of the commedia dell’arte in the 16th Century.

Small companies travelled through markets and fairgrounds performing and improvising comic stories featuring the same stock characters: the innamorati (young lovers); the vecchi (old men) like Pantalone; zanni (servants) such as Arlecchino, Colombina, Scaramouche or Pierrot; and the Harlequin.

In the 17th Century, adaptations of these characters became familiar in English theatre in plays called Harlequinades.

In the early 1700s, theatre manager and actor John Rich realised the potential of the commedia characters and made Harlequin the star of the entertainments. It was Rich's Harelquinades that developed the pantomime traditions of slapstick, chases, speed and transformations.

The Victorian era then saw the rise of the music hall and the demise of the traditional Harlequinade. The subject shifted to fairy tales or Robinson Crusoe; they started to be performed during the festive period, and pantomimes as we might recognise them today appeared on the scene.

It became traditional for a young actress to take the part of the hero, and a comic actor to portray an old woman, called the dame.

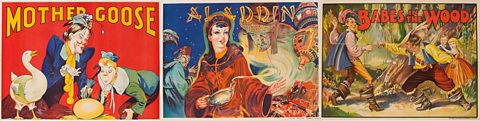

Popular pantomimes in the 20th Century included Cinderella, The Babes in the Wood, Aladdin, Robinson Crusoe, Mother Goose, and Blue Beard.

Twenty years into the 21st Century and many aspects of pantomime remain unchanged from these 20th-Century shows.

We asked panto legends, Kenneth Alan Taylor and Johnny McKnight, how they stop panto becoming a thing of the past?

'Please, please, no politics'

Kenneth Alan Taylor has worked in theatre for over 60 years. He is a legend in the panto world and has written, directed and starred in productions.

He hung up his dame costume in 2012, but continues to write and direct pantomimes at the Nottingham Playhouse - this year it’s Sleeping Beauty.

ґуПуґ«ГЅ Bitesize caught a few minutes with Kenneth during rehearsals to ask what he loves so much about panto.

“It’s probably the first time children see theatre,” he said.

“It’s absolutely vital that you give them good production values, and something that they can relate to without talking down to them.”

Kenneth said pantomime should be for the whole family without the fear of offending anyone’s grandma. It’s the “familiarity and the safety” that families return for, he said.

Kenneth did his first pantomime in 1959.

He said he likes to keep the story and themes of his pantomimes true to tradition, but when he looks at his early scripts the scenes are much longer than they are today.

He said he has to “sharpen up” pantomime scenes since the attention span of children seems to be much shorter now.

A self-professed “stickler for tradition”, Kenneth now sees a lot of pantomimes that don’t use the traditional formats, like which side of the stage the fairy enters from.

He prefers to keep things traditional since in his view, pantomime is “part of theatrical history”.

Kenneth describes his pantomimes as “squeaky clean”, “not because I’m a prude” but because he likes to keep things suitable for the whole family.

And even with an election right in the middle of panto season…

“Please, please, no politics. We don’t mention Brexit,” he said.

'The joke has to be on me'

For Johnny McKnight, writer, director and performer of pantomime, it’s all about adapting to a changing audience.

Johnny said he loves seeing the audience grow up as families return year-on-year.

He likes his pantomimes to be “anarchic and wild”.

“There’s no stuffiness or pomposity in panto that live performance can be guilty of,” he said.

Johnny has done pantomimes where rather than ending with a wedding between the prince and the princess, the prince falls in love with his right-hand man and chooses to marry him instead.

Last year Johnny felt he had “pushed the boat a little bit”, when he did a love story from the beginning to the end about two men in Mammy Goose at the Tron Theatre in Glasgow.

Johnny tries to reflect what he sees in real life on the stage:

“I don’t think I’m being revolutionary, I think I’m just being representative of the world we walk in,” he said.

He thinks gender balance is important in his pantomimes and has tried to have a 50:50 split in his cast since he started directing in 2007.

“I find it really weird how there was usually around nine men to two women. That never really made sense to me because I know so many brilliant, funny women.

“So many pantomimes don’t let women get a joke or be funny, which is insanity,” he said.

But, even with these adaptations, “it’s still a pantomime first and foremost,” said Johnny.

“You can still do the same jokes but without bringing anybody down, or laughing at any minority groups.

“The joke has to be on me, not on anyone else,” he said.

The silver screen Shakespeare quiz

The Lion King, West Side Story, She's The Man. Can you guess which works of Shakespeare these famous films are based on?

The fabulous history of drag

From the Shakespearean stage to serving up runway realness.

Drama essentials

You've got a brief overview, but dive deep into dramatic devices with this handy KS3 guide.