In 2017, вҖҳfake newsвҖҷ became Collins DictionaryвҖҷs word of the year and itвҖҷs remained in the headlines ever since. Although the phrase might appear to be a modern invention, examples of it can be found throughout history.

From ancient Rome up to the present day, stories that are not true or are meant to be misleading have been used to make money, change peopleвҖҷs views and opinions and make us question who we can trust.

Now, with the explosion of the internet and social media, it seems to be everywhere and travels faster than at any other point in history.

Ancient history

Around 2000 years ago, the Roman Republic was facing a civil war between Octavian, the adopted son of the great general Julius Caesar, and Mark Anthony, one of CaesarвҖҷs most trusted commanders.

To win the war, Octavian knew he had to have the public on his side вҖ“ winning important battles helped, but if the people didnвҖҷt like him, he would not be a successful ruler.

To get public backing, Octavian launched a вҖҳfake newsвҖҷ war against Mark Anthony.He claimed Anthony, who was having an affair with Cleopatra, the Egyptian Queen, didnвҖҷt respect traditional Roman values like faithfulness and respect. Octavian also said he was unfit to hold office because he was always drunk.

Octavian got his message to the public through poetry and short, snappy slogans printed on to coins. It was a bit like an ancient version of a politician today releasing a book or sending out a social media post. Octavian eventually won the war and became the first Emperor of Rome, ruling for over 40 years.

18th century

After the invention of the printing press in the 15th century, news (both real and fake) was able to spread faster than ever before. This technology meant books and other documents could be produced much quicker than any handwriting.

In the mid-1700s, the printing press helped to spread fake news about George II, who was the King of Great Britain and Ireland at the time. The King was facing a rebellion, and relied on being seen as a strong leader to make sure the rebellion didnвҖҷt succeed.

Fake news about the King being ill was printed from sources on the side of the rebels. It didnвҖҷt take long before these stories were seen by other printers who then republished them. This harmed the KingвҖҷs public image, and although the rebellion wasnвҖҷt successful, showed how fake news can be used to try and change peopleвҖҷs opinions.

The same thing happens today when a fake story is published on purpose to harm someone else. Unfortunately, if it isnвҖҷt fact-checked and gets shared by people or organisations thinking it is true, some of whom might have large followings, it starts to be taken seriously and the more it is shared the quicker it spreadsвҖҰ unchecked.

Creatures on the Moon

By the 19th century, newspapers were an easy and cheap way of getting news out to the public. In America, printing became so cheap that some papers could be bought for just a penny.

One of these papers, The New York Sun, published a series of articles in 1835 about life on the Moon. They described how there were fantastic animals such as unicorns, two-legged beavers and even flying bat-men!

Ian Hislop investigates the truth behind the Great Moon Hoax. From 'Ian Hislop's Fake News: A True History' (ҙуПуҙ«ГҪ Four)

They wrongly claimed the discoveries were made by a well-known astronomer at the time, which helped people to believe the story was true.

These made-up stories were very popular, and sales of the paper shot up as readers all wanted to find out about this amazing вҖҳdiscoveryвҖҷ.

The writer of the articles knew the story wasnвҖҷt true and had meant for this to be satire. This is when a writer uses humour and exaggeration to make fun of silly ideas, in this case that there were creatures living on the Moon.

It still happens today a lot on social media. Sometimes comedy and satirical accounts will publish a made-up story supposed to make us laugh, and people share it thinking itвҖҷs true. This is another form of fake news.

Fake news and war

Propaganda has been used in wars throughout history to try and change peopleвҖҷs views. This is a type of fake news where false information is used for political gain. It can help change public opinion by persuading people that their country should go to war, or convince them the other side is their enemy.

In 1898, a United States Navy ship called USS Maine sank in Cuba. Some of the newspapers at the time blamed the Spanish for the sinking, and used artistвҖҷs illustrations of a dramatic explosion to convince readers that this was true. However, there was no real evidence of this being a fact.

Americans now saw the Spanish as the enemy. A few years later the Spanish-American war broke out. The false reports had worked.

The story of how a fake news headline led to war. From 'Ian Hislop's Fake News: A True History' (ҙуПуҙ«ГҪ Four)

Closer to home, in 1917 during the First World War, British newspapers such as the Times and the Daily Mail ran a gruesome story claiming that the Germans were extracting fat from the bodies of dead soldiers on both sides of the war to make soap and margarine.

The story came from an official British government department and was spread to the press. The officials knew that this story wasnвҖҷt true, but it helped persuade readers that the Germans were a barbaric enemy and convinced many that they had to be defeated.

Fake news now

In recent years, there has been an explosion of fake news as false stories are shared widely on social media without being fact-checked. Cheap and portable access to the internet across the globe means stories can spread in a matter of seconds and minutes rather than days or weeks. Many of these stories are completely made up and can make money from advertising - the more clicks a website gets, the more money it makes.

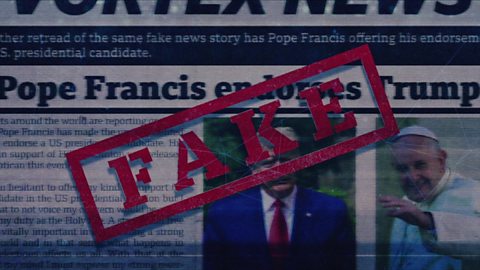

This often leads to clickbait, eye-catching but misleading headlines, designed to get people to click on links. Its purpose can be to generate clicks and advertisement money, but it can also be used to influence public opinion with headlines that appeal to our beliefs. This happened a lot during the 2016 US presidential election, where fake news about the candidates spread and could have influenced the public on how they voted.

As fake news became more widespread, the term itself began to change. Politicians began to use the phrase to attack news organisations they disagreed with, accusing them of being the ones who spread fake news. By calling real news вҖҳfake newsвҖҷ, it allowed real вҖҳfake newsвҖҷ to get more attention as people didnвҖҷt know who to trust вҖ“ very confusing!

The future of fakes

Over the years, the development of technology has helped fake news spread through inventions like the printing press, photography and social media.

Videos were usually a fairly reliable source of news, as they canвҖҷt be faked as easily as a photograph or headline. However, the reliability of video sources is now under threat from deepfakes. These are videos that use computer software and machine learning to create a digital version of someone. Normally itвҖҷs used to put the face of a celebrity or politician on to someone elseвҖҷs body.

ҙуПуҙ«ГҪ My World presenter Radzi Chinyanganya dives into the world of deepfakes.

As the technology improves, deepfakes will become more realistic and harder to notice, but many amateur deepfakes can be spotted by unusual flickering or blurring around the face, so keep an eye out for that if youвҖҷre suspicious about a video youвҖҷve seen.

For more advice on how to spot fake news online and on social media, try out the resources below and explore the rest of Fact or Fake? with ҙуПуҙ«ГҪ Bitesize.

Where next?

What's so bad about fake news?

Vick Hope gives the lowdown on different types of fake news and how they affect us.

How does fake news spread?

Vick Hope finds out how fake news plays on our emotions and why we should pause before we share.

What is fake news? - CҙуПуҙ«ГҪ Newsround

My World, the new ҙуПуҙ«ГҪ programme for young people around the world has been looking at what fake news is and how journalists can help tackle it.

Fact or Fake?

Find out how to spot and stop fake news with ҙуПуҙ«ГҪ Bitesize.