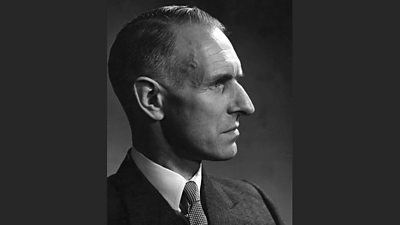

Image: Comet, a baby elephant from Chessington Zoo, was too big for the lift and refused to walk upstairs, so a camera was brought down to the terrace for his appearance in "Picture Page" handing a meal to Joan Miller and Leslie Mitchell, February 1939.

The Director of Television for the ����ý, Gerald Cock had said that "informality and brightness" were to be the keynotes of the new service. And in the nearly three years of television between the 1936 launch and 1939 closedown, programmes mostly lived up to that promise.

Not every item was light and entertaining, of course. The schedules were punctuated with illustrated talks about modern art, and demonstrations about exercise, cookery or beauty-tips. But, as this news footage from 1937 shows, the most striking characteristic of the first six months was the large amount of simple entertainment - and the overall variety:

Given how little money was being spent, and how few people were watching – tens of thousands at most, rather than millions – one remarkable feature of these early years is the number of high-profile celebrities who were willing to make the journey to Alexandra Palace to go before the ����ý cameras.

According to Cecil Madden, much of this was down to his team taking advantage of the fact that many actors, singers and dancers were simply curious about the new medium and wanted to see it for themselves. But in a short filmed interview many years later, Madden suggested there was another reason: the sheer quantity of high-class entertainment being staged in London’s West End in the late-1930s provided an overflowing reservoir of talent from which the ����ý could draw:

The Radio Times schedules also reveal quite how many drama productions were broadcast pre-war. Madden said that "a play-a-day" was the aim. Although this wasn't quite achieved, there were plenty of highlights: broadcasts of scenes from TS Eliot's Murder in the Cathedral, a large-scale production of Cyrano de Bergerac, and, in November 1938, even a transmission of J.B. Priestley's When We Are Married relayed directly from a West End theatre in London.

It was often easiest to get actors to come to the studios on a Sunday, and so the Sunday Night Play was regarded as something of a special treat – as we see in this short film extract:

Most of the television plays were done simply by inviting the cast of a West End show to travel the short distance to Alexandra Palace and recreate their stage performances for the cameras. But as Madden reveals in his oral history interview, this wasn't ever a purely London affair. There was a chance to secure talent from further afield:

The most popular and critically lauded programme of all before the War, however, was the magazine show Picture Page, broadcast twice a week:

In fact, the very first edition of Picture Page had been transmitted, rather surreptitiously, nearly a month before the ����ý's television service was formally launched on 2 November 1936.

Test broadcasts to the Radiolympia Exhibition had ended by October: Alexandra Palace staff were supposed to be concentrating their efforts on getting ready for the launch. But, as Madden explains in his oral history interview for the ����ý, he and his team were so keen to see if they could build on the success of the variety show they'd produced for Radiolympia that they jumped-the-gun:

The first ever edition of Picture Page was therefore the one broadcast in October 1936 – and the edition transmitted on 'opening night' was actually the second edition.

In any case, so successful was it that it was to run for 262 editions and a total of seven years – it started-up again after the War. Writing in The Listener in July 1939, Grace Wyndham Goldie judged Picture Page to be "one long triumph":

There is something of everything and nothing for long...It is, in fact, a kind of high speed television circus.

Picture Page's format offered elements of a traditional variety show – various stage acts, such as jugglers or knife-throwers, doing a turn for the cameras – mixed with more topical interviews. But the most famous element of each show was the device Madden and his team had created for linking each item: the Canadian actor Joan Miller sitting at a mock-up of a telephone exchange 'switching' the viewer through to each item in turn.

What television viewers didn’t know was that Miller was 'cued-in' by the studio director on each occasion by being given a 'mild' electrical shock through wires attached to her ankles. In between transmissions, the main task the Picture Page team faced was the unending search for suitable guests. In his oral history account, Madden explains how it was done:

By 1939, ����ý TV had shown variety acts, ballet, dramas, cartoons, newsreels, talks and demonstrations, operas, gardening, boxing, the Boat Race, Trooping the Colour, the football cup final, Wimbledon, Test Matches, and music concerts. A great deal of American showbiz talent was on the air regularly, too. The audience had its favourites, of course.

Letters to the ����ý showed that they especially liked the friendly tone of the key announcers – Leslie Mitchell, Jasmine Bligh, and Elizabeth Cowell. They also made clear their least favourite programmes: 'morbid' plays, continental films, and ballads, came out particularly badly.

There were also grumbles in the press about how few hours a day the ����ý was broadcasting: two hours daily, wrote the Daily Express in September 1937, was "woefully, ridiculously inadequate".

The main reason for such frugality was financial. Before 1938, the ����ý was only allowed by the Government to keep 75% of the licence-fee revenue; it was also trying to expand its Empire Service (the forerunner of the World Service) at this time. Unless large sums of money were taken away from radio, television would continue to survive on a shoestring budget, without the studios, cameras, or staff that would allow it to expand its schedule.

Despite all this, public interest in television was growing steadily. By the beginning of 1939, the number of people owning sets had grown to nearly 20,000. It was even predicted that by Christmas that year, as many as 100,000 sets might be sold. It wasn't to be.

On 1 September 1939, at the outbreak of war, Douglas Birkinshaw, the ����ý engineer in charge at Alexandra Palace, received a message that transmissions should cease. The ����ý’s pre-war television service ended abruptly with a Mickey Mouse cartoon and then, without ceremony, there was a total Closedown.

Who was Cecil Madden?

-

Who was Cecil Madden?

Cecil Madden joined the television service in 1936, and brought to his new job a fascinating range of experience – both inside broadcasting and out. In these oral history records, he recalls his background before joining the fledgling ����ý Television Service.

Search by Tag:

- David Hendy

- Gerald A. Cock

- Television Demonstration Film

- Cecil Madden

- Birth of TV

- Voices of the ����ý

- Murder in the Cathedral

- Cyrano de Bergerac

- When We Are Married

- Sunday Night Play

- Alexandra Palace

- Thank You Ally Pally

- Picture Page

- Radiolympia Exhibition

- The Listener

- Grace Wyndham Goldie

- Ivor Novello

- The Boat Race

- Trooping the Colour

- Wimbledon

- Leslie Mitchell

- Jasmine Bligh

- Elizabeth Cowell

- Licence-fee

- ����ý Empire Service

- Douglas Birkinshaw

- Mickey Mouse

- ����ý Television wartime closedown