Before the ����ý began regular broadcasting from Alexandra Palace aspiring "lookers-in" within signal range, as viewers were then called, were able to pick up the low-definition 30 line transmissions produced by Baird Television. From September 1929 these experiments, broadcast after radio had closed down for the day, were routed via the ����ý's 2LO medium wave transmitter located in Selfridges department store in London's Oxford Street.

In the days before synchronisation, sound and vision had to be broadcast separately due to the large bandwidth of television. Pioneering viewers would have had the disconcerting experience of watching, in two-minute rotations, silent moving images followed by the image-less sound of what they had just seen. The completion of the dual transmitter station at Brookmans Park by March 1930 solved this problem, but did not diminish the financial and practical challenges of watching television.

The 1928 Baird Dual Exhibition Receiver Televisor cost an eye-watering £40 and even then did not include the radio receiver that was required for audio reception. Nevertheless, its wooden box casing earned it the affectionate nickname of 'Noah's Ark'.

Meanwhile, the 'Tin Box' Televisor from 1929, with its large disk design and metal exterior, was manufactured for Baird by Plessy and sold for a much reduced, but still expensive, £18. The determined DIYer could also purchase kits that were based on the internal mechanisms of the televisor such as internal spinning disks, mirror drums and neon lamps.

By 1934 the Daily Express was offering readers the opportunity to buy kits made by Mervyn for just £5 9s 6d. Early television was emerging as either an elite pastime, or one for the amateur engineer. As the ����ý Director of Programmes Roger Eckersley witheringly put it:

television sets will be so expensive as to be the toys of the favoured rather than the pieces of furniture in the homes of the proletariat.

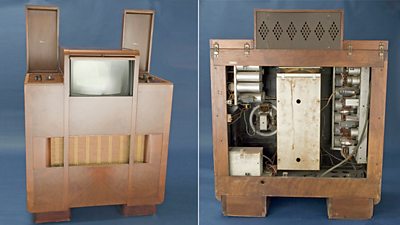

The theme of television as furniture was reinforced by the arrival of the Marconi-EMI television system that broadcast on 405 lines. The sets themselves were of a heavy hardwood outer design with large cathode ray tubes to receive the electronic image.

The Marconiphone 701 from 1936 had a mahogany cabinet and dense internal mechanism. Importantly, however, it allowed viewers to switch between the Baird (now 240 lines) and Marconi-EMI high definition systems that alternated each week for the first four months of the Television Service from Alexandra Palace.

In his ����ý Oral History interview, engineer James Redmond reflected on the experience of watching television before the war.

The novelty of television, prior to the inauguration of the service on 2 November 1936 was a cause for concern at the ����ý. What should members of the public with access to the new medium expect, both in terms of performance and televisual experience?

To prepare audiences, on 20 October 1936 the ����ý broadcast, via radio, a history of television Past, Present & Future, in which the ����ý's Chief Engineer Noel Ashbridge explained the technical differences between sound and vision broadcasting.

The weekly switches between the Baird and Marconi-EMI schemes arguably caused the greatest difficulty for staff at Alexandra Palace who had to manage the frenzy of this experimental phase. It also meant that, in effect, television had two launches – one for each system.

For Tony Bridgewater and James Redmond, who worked on the Baird and Marconi-EMI operations, respectively, these first few weeks revealed the technical specificities and peculiarities of both.

As had been the case a decade earlier, the ����ý was concerned that its watching audience should appreciate the behind-the-scenes technical story of how television reached them when the service re-launched in 1946. To this end, Jasmine Bligh took viewers on a journey into television.

After the war television re-emerged into a new world of possibilities. The technical capacities and experiences gained between 1936 and 1939 enabled the ����ý to embark on an ambitious postwar programme of expansion. The number of combined television and radio Licenses in the UK grew from just 14,560 in 1947, when they were introduced, to nearly seven million a decade later.

Supporting this growth was the development of a network of transmitters that by the time of the 1953 Coronation offered an almost nationwide service. The technical infrastructure built around the broadcasting of sound and vision, from the studio to the home, meant that television was here to stay.

There remains, however, an important footnote in the history of television that reveals its wider contribution to British society. Although preceding the Second World War by nearly three years, there was a hidden dimension of the Television Service that had particular relevance to the coming battle. The parallel development in the 1930s of television and radiolocation, as experimental radar was then called, indicates the important role that broadcasting played in the latter’s development.

The transmission and reception (and deviation, in the case of radar) of ultra-short radio waves was fundamental to their respective success. And, by extension, was the use of transmitter valves and cathode ray tubes, which were common to both. While the Selsdon Committee considered the future of television, the UK's Air Ministry instructed the Rector of Imperial College Henry Tizard to establish a committee to explore whether radio detection could provide Britain with an early warning system of air attack.

As a result, in September 1935 orders were given to build a series of radiolocation stations around the coast of the United Kingdom. The “Chain Home” network, as it became known, was brought into operation on 3 September 1939, the day war was declared in Britain. At the least, television offered a credible explanation for the production of vital shared components, while keeping the development of radar a secret.

It was along these lines that Lord Swinton, Secretary of State for Air during this crucial period, informed the ����ý’s Ian (later Lord) Orr-Ewing, by then in military service, of the vital role television had played in the defence of Britain.

Test Cards

Test Cards were designed to calibrate the fidelity of an image at both the television camera and receiver ends of the transmission process. Appearing first as a 'Tuning Signal' in 1934, as part of the Baird 30-line experimental broadcasts, over the subsequent eight decades successive generations of Test Card have become subtly incorporated into the cultural experience of television watching.

Much less visible now than they used to be, as a result of the Ceefax and Oracle teletext services and then the advent of round-the-clock and digital programming, Test Cards nevertheless retain an emotional appeal for many who experienced them. This is partly explained by the visual components – most popularly exemplified by the 1967 image of a girl playing noughts and crosses with a toy – but is also a reflection of interest in the musical accompaniments that included a wide range of significant, and sometimes original, orchestration.

As the below compilation of Test Cards through the ages (music included) demonstrates, it was the aesthetic qualities as much as their engineering attributes that help explain the enduring significance of Test Cards to the history of television in the United Kingdom.

With thanks to Stuart Montgomery and Frank Mitchell of the .

-

First published in 1972, ����ý Publications ©1972. PDF version with thanks to Nick Cutmore and Philip Laven.

Search by Tag:

- Technology

- Birth of TV

- Elinor Groom

- Alban Webb

- Alexandra Palace

- Televisor

- Baird Company

- ����ý 2 LO

- Brookmans Park

- Marconi 405 line system

- Marconiphone 701

- James Redmond

- Noel Ashbridge

- Television, The Past, The Present, The Future

- Baird 240 line system

- Tony Bridgewater

- Jasmine Bligh

- Television is Here Again

- Licence-fee

- World War Two

- Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II

- Selsdon Inquiry

- Henry Tizard

- Ian Orr-Ewing

- Test Cards

- Tuning Signal

- Baird 30 line system

- Ceefax

- Oracle

- Television

- Voices of the ����ý