Today, television is an everyday technology – it is an established feature of our homes, and an ordinary part of our domestic routines. But what did people make of television in the 1940s, when for the vast majority it was still a strange, new and unfamiliar medium? How did people think that television would impact on their everyday lives, their family relationships and their domestic habits?

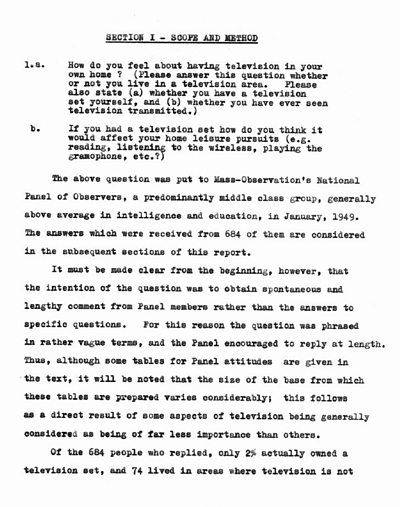

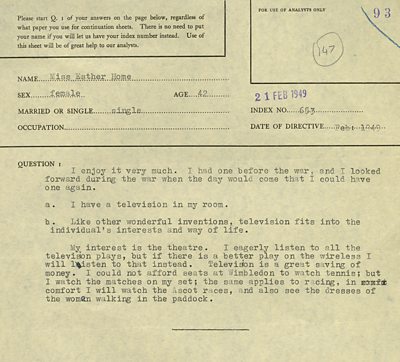

Some answers to these questions can be found in the archives of Mass Observation, the pioneering social research organisation that was launched in 1937 to document everyday life in Britain. In 1949, it asked how people felt about having television in their own homes, and how this might affect their "home leisure pursuits".

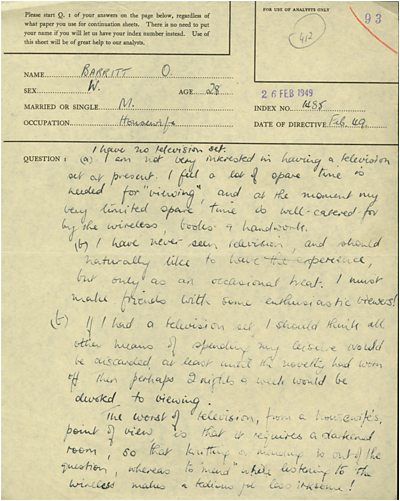

Perhaps unsurprisingly, women were much more likely than men to express concerns about how television might impact their ability to do domestic work: O. Barritt, a 28-year-old housewife, wrote that: “the worst of television, from a housewife’s point of view, is it requires a darkened room, so that knitting or mending is out of the question”.

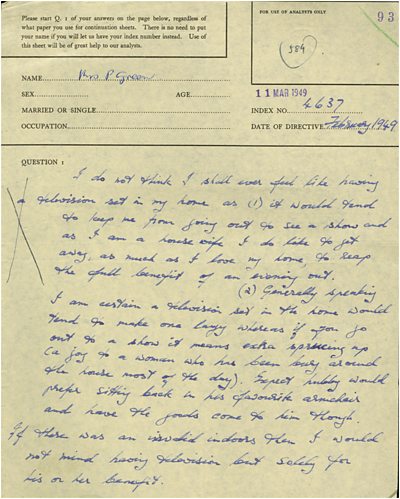

Other women were apprehensive about television because it might rob them of opportunities for dressing up and getting out - such as Mrs P. Green, who wrote that: "a television set in the home would tend to make one lazy whereas if you go out to a show it means extra sprucing up (a joy to a woman who has been busy around the house most of the day)."

As well as those who were ambivalent or anxious about television, there were also more positive evaluations of its potential to enrich or even to transform the experience of being at home. There was often a sense of wonderment at television’s miraculous abilities to 'transport' its audiences to far-flung places, or to allow them to witness public events like the Grand National, Wimbledon, and royal processions - all from the comfort of their living rooms, and all for free.

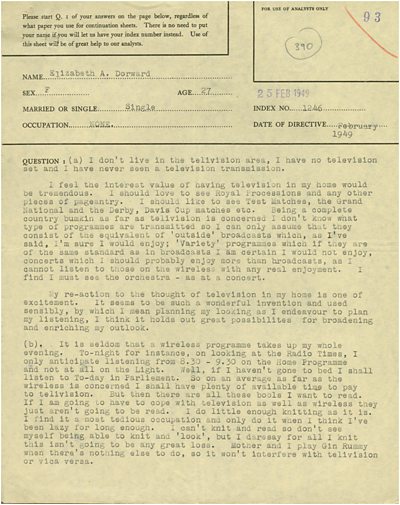

For 27 year-old Elizabeth A. Dorward, television was "such a wonderful invention" that held out "great possibilities for broadening and enriching my outlook".

Forty-two year-old Esther Home could not afford to buy tickets for Wimbledon or other sporting events, but having a television set now meant that "in comfort I will watch the Ascot races, and also see the dresses of the women walking in the paddock".

So, alongside apprehension, fear and derision towards this new cultural phenomenon, television was also deeply valued for its promise to grant ordinary people access to public spaces for the first time, and to bring the pomp and pageantry of national life into the home.

In this way, the Mass Observation survey of 1949 captures both the unease and the sense of awe that television inspired as it helped to transform the boundaries between public and private - and the very notion of what it meant to be 'at home'.

Documents supplied by the Mass Observation Archive, University of Sussex

Pre-war TV audiences - an early ����ý report

The Mass Observation directive of 1949 provides a vivid insight into television viewing in the early years after the war. The attitudes of viewers before the war are harder to come by – mostly because there were so few of them. But the ����ý began systematic audience research in 1936, and in January 1937 its new ‘Listener Research Section’ was asked to investigate the opinions of viewers of the two-month old television service. The 44-page report – marked ‘Private and Confidential’ was circulated to ����ý managers in February.

The first page explains how the information was gathered – revealing that the ����ý had communicated with 118 set-owners, and received replies from 74 of them. It was also acknowledged that many of these included people connected with broadcasting. In sampling terms, therefore, this was a small and somewhat unrepresentative group – though clearly it was all the ����ý had to go on.

The report itself found that three-quarters of those viewers who commented on ‘light entertainment’ programmes – namely variety and cabaret shows – were positive about them. Dramas and outside sporting events were also discovered to be overwhelmingly popular. Ballet, however, divided opinions for and against roughly equally. There was some disgruntlement about news films being repeated too often – and that they presented their information too quickly.

‘Studio demonstrations and talks’ came off worst. They were disliked by two-thirds of the sample. The report noted that, “Disapproval concentrated largely upon demonstrations of cooking, washing, ironing, etc., which were condemned as of little interest to those who could afford television sets” – an acknowledgement that, in 1937, ownership of a TV set was still very much a middle-class affair.

Apart from all the feedback about programmes, the research also revealed one other interesting feature of early TV viewing: that passing motor cars almost always interfered with reception.