The Cold War threat of nuclear annihilation sparked a series of iconic protest movements in the UK. But whilst the ����ý helped to convey the disarmament message to a wider public through its reporting, did anyone in authority truly listen? And if so, to what effect?

The Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) was launched in 1957 to challenge the Cold War’s logic of ‘mutually assured destruction’. Its now universally-recognised logo, juxtaposing the semaphore letters N(uclear) and D(isarmament), was designed by Gerald Holtom, a World War Two conscientious objector, and symbolised his fears:

I drew myself: the representative of an individual in despair, with hands palm outstretched outwards and downwards in the manner of Goya’s peasant before the firing squad.

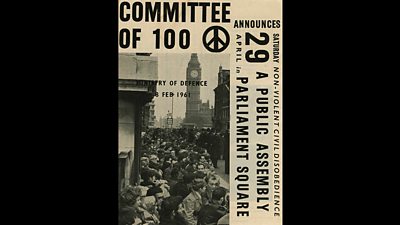

CND soon gained prominence thanks to the protest march from London to the UK’s weapons research centre at Aldermaston, Berkshire, in 1958. A shift to more direct action in 1961 saw 4,000 CND demonstrators stage a sit-in outside the Ministry of Defence in London’s Whitehall, with over 1,500 arrested at Trafalgar Square. At Holy Loch on Scotland’s west coast, 350 protestors were also being gaoled for challenging the establishment of an overseas base for American submarines armed with ballistic missiles.

Amongst those imprisoned was 89-year-old philosopher Bertrand Russell. For Russell, and the Committee of 100, non-violent direct action was necessary to capture media interest, and breaking the law was justified to counter the far greater offence of nuclear war planning. In 1963, an off-shoot of the Committee of 100, Spies for Peace, revealed secret government preparations for nuclear war, including plans to police a devastated post-attack population. The story made headline news, but the press was quickly muzzled by a D notice (D for defence), where the government could cite national security to suppress information.

-

Policy statement of the Committee of 100, with thanks to the British Library.

Clearly, being heard was a challenge, but a group of young people were invited to contribute to ����ý 2’s long-running Let Me Speak show, hosted by the renowned journalist and broadcaster, Malcolm Muggeridge. Aired on Aug 1st 1964, they indignantly declared to bleary-eyed viewers still tuned in to the day’s final programme:

We're tired of seeing the disarmament talks get virtually nowhere at all while more and more nations plan to get nuclear weapons. We're sick to death of hearing all those fatuous clichés about the Communist menace and the need for Western unity.

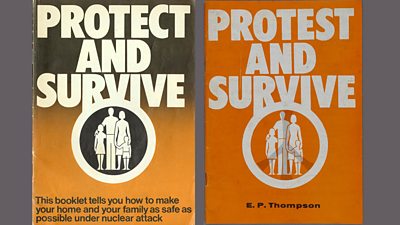

Was anyone listening? More than 20 years later in 1988, a ����ý retrospective of the Aldermaston march similarly asked, ‘did anyone in authority hear the chants of ‘Ban the Bomb’? It would seem not. Having already been dubbed the Iron Lady by Soviet commentators, Margaret Thatcher became prime minster in May 1979. In December, NATO opted to deploy American Pershing ballistic and Tomahawk cruise missiles in Western Europe to counter newly-developed Soviet weapons. Within days of this announcement, Soviet troops invaded Afghanistan, and US President Jimmy Carter called a halt to ongoing arms limitation talks. Within a year, Ronald Reagan had become US president, quickly bonding with like-minded Thatcher and in 1980, the UK opted to purchase the American Trident nuclear missile system. The Cold War was getting hotter.

European Nuclear Disarmament (END) was born in 1980 under the threat of ‘limited’ nuclear war between the superpowers across European territory. Urging the continent to join forces for peace ‘from Portugal to Poland’, END distinctively called on the USSR to disarm alongside the West. Equally daring was its concept of ‘détente from below’:

"The remedy lies in our own hands . . . We must commence to act as if a united, neutral and pacific Europe already exists. We must learn to be loyal, not to ‘East’ or ‘West’, but to each other, and we must disregard the prohibitions and limitations imposed by any national state . . ."

END quickly secured support from within the Soviet bloc, including former Hungarian prime minister Andras Hegedus and Russian dissident Roy Medvedev. It encouraged visits between country ‘working groups’, and support for dissidents, including Václav Havel in Czechoslovakia. Such dissidents in turn educated Western activists about the power of Soviet propaganda, and life under Soviet totalitarianism.

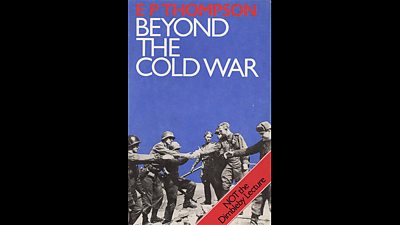

Yet whilst the ����ý invited END founders, including E.P. Thompson and Mary Kaldor, to debate, for example on Any Questions, END’s citizen diplomacy rarely grabbed the headlines. One exception was the furore in 1981 after Thompson was sounded out about– but not offered – the annual televised Richard Dimbleby lecture. In his oral history interview, undertaken by Frank Gillard in 1983, the corporation’s then Director-General Ian Trethowan recounted:

"... it was said that E.P. Thompson had been signed up for the Dimbleby Lecture… and that I had in my 'fascist and dictatorial’ way stopped this great .. great nuclear disarmer from... saying to the nation what it was about. In fact… it was perfectly clear that he knew that it was a sounding, it was not an actual engagement. Well as soon as I saw his name I said 'You must be mad you can't put this chap on, he is a rabid nuclear disarmer'. I said 'He is a very distinguished historian if you want to put him on the list as a historian ..three cheers... Anyhow there was a great public fuss and I was much belaboured as being brutal and repressive as an editor."

In the end, Thompson had his say, delivering his ‘Not the Dimbleby Lecture’ in Worcester, in which he argued that conflicts had become systematized, in ‘a ‘self-reproducing’ dynamic condition which, while postponing war, also postponed indefinitely the resolutions of peace’.

END’s vision aimed to challenge the propagandising on both sides of the Cold War divide that promoted theories of nuclear deterrence, which were opposed to unilateralism. And it seemed in 1981 that the message might be gaining ground when the Labour Party adopted a nuclear-free defence policy, despite a Gallup poll suggesting widespread uncertainty about unilateralism. In 1982, the ����ý’s Panorama speculated on the prospects of this policy, wondering: ‘Sense or Suicide? Is pulling down the nuclear umbrella the route to peace, or an invitation to war?’

In the event, Labour suffered a heavy General Election defeat in June 1983, blamed in part on its unilateralist commitment, although the newly formed SDP-Liberal Alliance helped split the anti-Conservative vote. Yet at the same time, President Reagan’s Star Wars initiative – designed to intercept incoming Soviet missiles in mid-air – helped fuel a CND revival, and mobilised mass demonstrations. Moreover, a new peace campaign was capturing the public’s imagination in ways that were unique and spectacular: The Greenham Common women’s protest.

In September 1981, a small group of women, plus a few men and children, arrived at Greenham Common Royal Air Force base in Berkshire, to deliver a letter. ‘We… have walked one hundred and twenty miles from Cardiff’, it began:

"We fear for the future of all our children, and for the future of the living world which is the basis of all life. We have undertaken this action because we believe that the nuclear arms race constitutes the greatest threat ever faced by the human race and our living planet. We have chosen Greenham Common as our destination because it is this base which our Government has chosen for 96 ‘Cruise’ [missiles] without our consent."

The Commandant invited them to stay, hospitality he surely came to regret: thus, the peace camp was established. There was little media reaction at first, nor when four women chained themselves to the fence, suffragette-style, demanding a televised debate with Defence Secretary, John Nott. Despite considerable correspondence with ����ý and ITV producers, no debate took place.

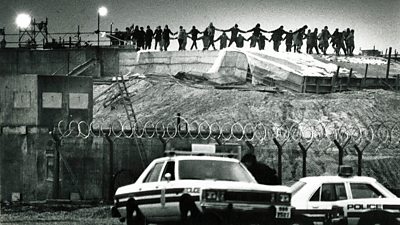

Yet over time, the camp would mesmerise the media with its women-led direct action, and tactics which – in addition the unusual but effective handwritten chain letter sent through feminist networks – culminated in the legendary ‘Embrace the Base’ protest in 1982, when 30,000 women joined hands around the 11-mile perimeter fence. Sympathy for the cause soared, with a Marplan Survey showing 66% of women and 55% of men supporting nuclear disarmament.

And Greenham women learned to use the media: favouring women journalists, photographers and lawyers to confront the dominance of men in those fields. Its most famous record was Raissa Page’s photograph of 44 women dancing on a missile silo at dawn on New Year’s Day, 1983. Page, from the pioneering all-women’s photography agency, Format, was quietly invited to witness the break-in, which refuted the government’s assertion that Greenham was the most secure base in Europe.

But such media successes came at a price, especially after Michael Heseltine became Defence Secretary in 1983. Charged with leading a counter-information campaign, he quickly set up a small propaganda team to brief opinion-formers, schmooze journalists, and counter the disarmament message. Groups such as Women & Families for Defence, led by Lady Olga Maitland, who later served as a Conservative MP, worked to undermine the feminist message in particular. Rebecca Johnson, who lived at Greenham for five years, commented:

"We’d gone from being, you know, these wonderful... housewives, mothers, grandmothers, to being this... aggressive rabble of dykes. And again, that was one of the first times that you just saw the media using this... pejorative sort of labelling of us as lesbian to – to somehow dismiss us or to try to get the people out in the public to see us as something less than human or certainly less than womanly."

Yet by December 1987, Presidents Reagan and Gorbachev had agreed an intermediate-range nuclear forces (INF) treaty, banning all land-based ballistic and cruise missiles. Greenham’s missiles were removed in 1989 and the site reverted to common land in 2000. Such change was surely in part thanks to the efforts of millions of peace protestors on both sides of the Iron Curtain.

Greenham’s anarchic community and inclusive politics – protesting against nuclear testing in the Pacific and uranium mining in Namibia, as well as patriarchal militarism – perhaps made it easy to mock. But Greenham was not just a lifestyle experiment. As with CND and END, it was a brave attempt to promote direct action, citizen diplomacy, and utopian dreams.

Such dreams were shaped and reshaped by an existential terror which drove people to protest. Yet there has been far greater nuclear proliferation since the supposed end of the Cold War. END founder Mary Kaldor theorises current ‘new wars’ as spreading and persistent, in a globalized war economy. In this context, the UK is not removed but involved, through terror management, arms trading, and nuclear arms hosting and development. And on 1 February 2019, US President Trump formally suspended the hard-won Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty. The following day, Russia did so too.

So, we must continue to ask – who in authority is listening?

Written by Professor Margaretta Jolly, University of Sussex.

Further Reading

With thanks to the British Library for use of materials relating to Sisterhood and After: The Women’s Liberation Oral History Project, at and to the Committee of 100, at Dreamers and Dissenter.

Johnson, R. 2009. Unfinished business: the negotiation of the CTBT and the end of nuclear testing, Geneva, UNIDIR.

Kaldor, M. 2012. New and old wars: organized violence in a global era, Cambridge, Polity.

Montgomery, V. L. 1956. The Panorama of Warfare in a Nuclear Age. Royal United Services Institution, 101, 503-520.

Smith, D. 1980. The European Nuclear Theatre. In: E.P.THOMPSON & SMITH, D. (eds.) Protest and Survive. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Jones, L. 1983. Keeping the peace, London, Women's Press.

Roseneil, S. 2000. Common women, uncommon practices: the queer feminisms of Greenham, London, Cassell.

Thompson, E.P. & Smith, D. (eds.) 1980. Protest and Survive. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Thompson, E. P. 1982. Beyond the Cold War, London, Merlin Press jointly with END.

Young, A. 1990. Femininity in dissent, London; New York, Routledge.