The ����ý had long wanted to broadcast direct from Westminster. But even in the 1960s, a majority of MPs were still reluctant to let in either microphones or cameras. Some feared they’d be caught napping, others that it would ‘change the character’ of the House, or that programmes such as Monty Python’s Flying Circus would use recordings to satirize them.

In his diaries, Richard Crossman recorded the Prime Minister Harold Wilson’s reaction to a 1966 proposal. If the ����ý had every debate recorded, Wilson asked, ‘would they be able to cut the videotape up and take a little bit of speech and introduce it into a magazine programme?’ ‘Certainly’, Crossman replied. ‘That’, Wilson concluded, ‘couldn’t possibly be allowed’.

But a growing number in the Commons were campaigning for change. During a 1972 debate the Conservative backbencher Brian Batsford argued it was wrong that public discussion took place in the ‘entirely unnatural environment’ of TV, ‘where those who are invited to take part are selected, not by you Mr Speaker, but by the broadcasting authorities’.

British voters, he suggested, were ‘more and more critical’ of politicians, and the introduction of cameras might ‘bridge the gulf which has widened so much between Parliament and the people’.

We should no longer accept the second-hand interpretations, the second-hand accounts, by the broadcasting authorities

- David Steel speaking in the Commons, 1972

Inside the ����ý, senior executives also spotted the advantage of relaying politics in a less ‘mediated’ form. At the start of the 70s, with industrial strife, conflict in Northern Ireland, tensions over immigration, end economic crises at every turn, they envisaged a Britain of deepening divides. Studio debates would be increasingly fractious and harder to manage. ‘What then is our public attitude?’ one of them asked. ‘It is to let the different voices speak for themselves.’

How to proceed? After the 1974 Election, there was a more willing generation at Westminster. Unfortunately, ����ý soundings revealed that televising the State Opening of Parliament that year had required a level of artificial lighting that ‘stuck in the gullets of many MPs’. It looked as if the best hope of the broadcasters now lay with the much less obtrusive medium of radio.

On 24 February 1975 a Commons vote, while rejecting cameras, finally approved the presence of microphones. Radio coverage of Parliament wasn’t made permanent for another three years. But in June 1975 there was a month-long experimental period. The Labour Minister Tony Benn was the first MP to be heard by those listening on Radio 4 medium-wave frequency.

Inside the ����ý, political reporters were delighted. Both the live broadcasts of major debates and the regular use of short recorded extracts in programmes such as Today in Parliament and Yesterday in Parliament had, wrote one senor editor, ‘introduced into broadcast journalism a whole new element of vast importance’. Another predicted confidently that it would ‘lead to heightened interest in the Parliamentary process’.

Listeners to Radio 4, many of whom were having their regular afternoon plays disrupted, were less convinced. Within the first two days of Radio 4’s coverage in April 1978, the ����ý received 343 phone calls and letters of complaint; by the end of May they’d received 2,799 – and only 31 letters of appreciation. Far from reconnecting with parliamentary democracy, the British public’s first reaction was to be appalled at the rowdy and posturing behaviour in the House, or confused by the arcane procedures. Sometimes they were simply bored.

Behind the scenes, however, there was growing momentum for radio to be joined by TV. This next interview offers a fascinating insight into why, in 1983, it was the Lords rather than the Commons, which first voted to let in the cameras. Margaret Douglas was then the Chief Assistant to the ����ý’s Director-General Alasdair Milne - and in this 1993 recording she explains her role in the negotiations...

-

9.3 MB

In February 1988, , MPs voted to let the Commons follow suit. On 21 November 1989, live television coverage began. Viewers had the strange experience of seeing only a series of static close-ups and the occasional ‘wide shot’ of the whole Chamber: to begin with, broadcasters weren’t allowed to use so-called ‘reaction shots’. The first MP to appear was the Conservative, Ian Gow.

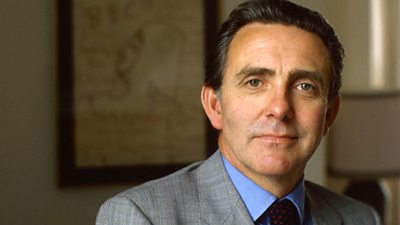

Since 1989, thousands of important debates and committee proceedings have been covered. But for most viewers and listeners the ritual of Prime Minister’s Questions epitomises Parliamentary broadcasting. Its combative nature has led to complaints about the trivialising of politics - a subject touched on in this next interview. John Cole was the Corporation’s Political Editor during the governments of Margaret Thatcher and John Major – and in this 1996 recording he recalls in particular Mr Major’s anxieties.

No to TV

On the 19 October 1972, MPs voted against broadcasting from Parliament - the latest in a long series of failed attempts to allow cameras and microphones into the Commons or Lords. The very next day, the ����ý’s Director-General Charles Curran met his senior news editors to discuss where this left the Corporation. A note of the meeting is held in the ����ý’s written archives:

‘It was generally agreed that the vote in the House of Commons on the previous evening had probably shelved the idea of broadcasting parliamentary proceedings for about five years, though it was just conceivable that after a year or two someone might suggest broadcasting them on radio alone.

It was generally agreed that the vote in the House of Commons on the previous evening had probably shelved the idea of broadcasting parliamentary proceedings for about five years, though it was just conceivable that after a year or two someone might suggest broadcasting them on radio alone.

CA to DG [John Crawley, the Chief Assistant to the Director-General] had listened to the debate in the Commons and had gained a new understanding of the House as a club for which members of all parties had a special affection. He had also been reminded of the deep hostility of the House towards the press and broadcasting journalists, especially those of the ����ý… This hostility, combined with a desire to preserve the club-like atmosphere of the House of Commons, had been sufficient to defeat the motion. Peter Scott [Peter Hardiman Scott, the ����ý’s Political Editor] agreed.

However, three days later, it was thought some progress might still be possible. The minutes of the ����ý’s Board of Management for 23rd October 1972 record the Chief Assistant to the Director-General reflecting further on the vote:

A lengthy setback was likely as far as televising Parliament was concerned, but the subject might be revived as a “radio only” issue within a comparatively short time.

This was prescient. It was to be more than a decade until cameras were allowed into either Chamber. Within three years, however, live radio broadcasts had begun.

Wedgie’s Triumph

When the first live broadcasting from the House of Commons was heard on ����ý Radio 4 on Monday 9th June 1975, a ����ý editor immediately noted that ‘certain politicians had taken to the new conditions like ducks to water’. Among them it seems was the Labour Minister Tony Benn, one of the very first to be heard on air that afternoon. The next day his performance was scrutinised by the Press - and by his somewhat exasperated Cabinet colleague Barbara Castle, who recorded this in her diary:

The newspapers are full of Wedgie’s “triumph” at Questions yesterday… Some of the most ecstatic comments were from enemy papers. “Big Benn is the star of the air!” said The Sun. “Commons radio starts with sparkling Benn cut and thrust” said the Financial Times. “Benn a hit in radio Commons”, said the Daily Telegraph… Which confirms my view that (a) the press are doing more than anyone else to build up Wedgie and (b) that you have got to have certain attributes to be a successful rebel: you must shine on the platform and in the House. Wedgie does both, which is why he can get away with murder.

Barbara Castle, The Castle Diaries 1974-76 (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1980)

Rubbing shoulders

In November 1974, the ����ý’s Director-General, Charles Curran, had suggested that broadcasters needed to be based inside Westminster rather than covering events remotely because ‘politicians invariably seemed to acquire a respect for people whom they knew’. But for those journalists who got the job conditions behind-the-scenes proved to be far from ideal - as many of the ����ý’s written archives from the period reveal.

Space in the Palace of Westminster was limited. In April 1975, as the first experimental period of live broadcasting neared, the ����ý’s outgoing Political Editor, Peter Hardiman Scott wrote to the Leader of the House and the Sergeant at Arms to complain: the commentary seats – one for the ����ý and one for the London commercial station LBC – were far too close for comfort, he claimed. They offered ‘very cramped conditions for two people who are likely to be working under some strain’.

The rival broadcasters remained just 18 inches apart, and in June, once the live broadcasts had begun, another ����ý journalist was complaining of ‘unhealthy’ conditions in the commentary box: ‘if a long debate were to be covered it would be vital to change commentators every two hours’, he warned.

Among ����ý managers, though, a bigger concern was the poor image that listeners were apparently getting of MPs as a result of their rowdy behaviour – made worse, the Corporation’s engineers thought, by microphones that failed to distinguish between those making a speech and those reacting to it.

In July 1975, the Head of Radio Drama, Martin Esslin, was comparing the noise of the Commons to badly rehearsed crowd scenes – ‘always unconvincing and always loutish’. Others in Broadcasting House now began to wonder if coverage on TV might be a better option after all: viewers, they reckoned, might make more sense of all the ‘offending noises’ if only they could see who was making them and why.

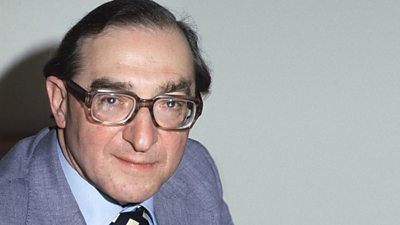

The Controller attacks

When live radio coverage of Parliament was made permanent in 1978, most broadcasts were on Radio 4. But the network’s Controller, Ian McIntyre, was not a fan. He’d already attacked colleagues in news and current affairs for what he saw as too much emphasis on immediacy and not enough on elegantly crafted analysis. So on 12th April 1978, as senior editors gathered for their regular weekly review of programmes, McIntyre tore into coverage of the Budget – as the minutes of the meeting reveal:

Much of the material from Parliament so far had proved very intractable, and during this particular afternoon he [McIntyre] had felt he was witnessing a skilled potter offering a lump of raw clay to his customer, instead of a properly fashioned artefact.

The Controller went on to say that:

… much had been made of “furthering the democratic purpose” by broadcasting from Parliament, but the ����ý’s Charter contained no such requirement. The ����ý’s business was making programmes, not relaying the source material for them, and making programmes was a highly skilled artificial business. As for the immediacy of broadcasting from Parliament, he was all for immediacy when it enriched the final result, as had happened in the case of Today in Parliament. But there was a difference between immediacy and incontinence… Meanwhile, he regarded many relays from Parliament as “non-broadcasting” if not “anti-broadcasting”.

After the meeting, one of McIntyre’s bosses asked if he often committed ‘professional suicide’. Four months later Radio 4 had a new Controller. The parliamentary broadcasts remained.

The cameras arrive

What was it like for those working behind the scenes in the early days of televising Parliament? And how much difference did it make to have not just microphones but cameras filming the business of MPs.

One of those most intimately involved was Suzanne Franks, now Professor of Journalism at City University. In the late-1980s and early-1990s, she helped produce coverage, first of Parliament’s select committees, and then of debates in both Chambers. In this recently recorded interview, she recalls her period working at Westminster.

Beyond Westminster

When live broadcasting from Parliament became permanent in 1978, the new Controller of Radio 4, Monica Sims, wasn’t against the whole idea, like her predecessor, McIntyre. But she certainly believed too much political reporting was obsessed with what’s nowadays called the ‘Westminster Bubble’. It wasn’t enough to shift politics from the TV studios back to Parliament, Sims thought.

What was needed was political reportage that broke free of the Chambers and the Lobby and spoke to the country at large. She also wanted Parliamentary broadcasting to be woven more carefully into the fabric of normal output - as she explained in an interview recorded with David Hendy in 2003:

I think, because of my Woman’s Hour and Children’s [TV] background – I wanted to take more account of the listeners’ needs, and what they said they wanted… I did think that some of the news and current affairs was too Westminster/London-orientated. I was very anxious, straight away really, to involve the rest of the country much more… I actually made spaces for a news bulletin on the hour all through the day and all through the evening, which wasn’t there before, as a regular part of the schedule…

But I also wanted to increase the accessibility of a lot of the current affairs programmes, to a slightly less specialist audience… Which is why I, in the end, after a very long argument, managed to get Westminster incorporated into the Today programme, instead of a separate switch-off for most of the listeners. Because within it, slightly shortened, it got a much wider audience…

But John Cole [the ����ý’s Political Editor, 1981-92] didn’t approve of that, because nobody associated with Parliament could ever contemplate losing a minute of actual Parliamentary reporting. They just wanted as much as they could, in case the MPs, particularly, in case their constituents happened to hear them speaking.

Sims struggled to get the changes she sought. But she certainly wasn’t the last to worry about whether Parliamentary broadcasting was connecting with wider audiences and their everyday concerns, as her predecessors had always hoped it would when they campaigned for it back in the ‘60s.