Old ����ý hands often take time in retirement to look back at their time in the Corporation. And one theme that recurs more often than any other from oral history recordings and published autobiographies, is the powerful sense these men and women had of an overriding ethos that attached to the Corporation – one that was inspired by the organisation’s founding figure.

It has come to be called ‘Reithianism’ – a baggy and vague term that often conjures up something forbidding: a backward-looking Victorian paternalism, the notion of an ‘Aunty’ that ‘knows best’. But in essence Reithianism was also about looking to the future. It was a philosophy that saw broadcasting as something that should strive to do more than simply reflect the present state of affairs: it was something that needed to imagine other ways of being in the world.

In 1968, it was Harman Grisewood’s turn to look back on his own long and distinguished career. It stretched from his being a bit-part actor and announcer at Savoy Hill during the 1920s all the way through to being one of the Director-General Hugh Carleton Greene’s most senior right-hand men in the 1960s. What, Grisewood asked himself, had it all been for? His answer: the job was never done if it only reflected faithfully ‘what goes on and what motivates the present-day world’. ‘Reporting’, he added, is not ‘the total duty of the ����ý’. Programmes also needed to ‘discriminate in favour of what is vital’.

Grisewood was a conservative – both socially and politically. One of his ����ý colleagues, Charles Siepmann, came very much from the opposite side of the political spectrum. In his oral history, Siepmann, who had been a Head of Talks Programmes in the 1930s, described radio as a tool for building what he called a ‘New Age of Cultural Communism’.

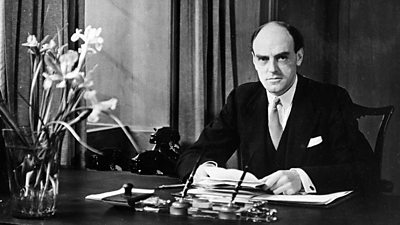

What Grisewood and Siepmann had in common was a profound faith in the idea that broadcasting, if it was in the right hands, really could change people – and through changing people, change society – for the better. It was this idea that broadcasting should lead public taste rather than simply follow it that connected both men umbilically with the philosophy of the ����ý’s founding figure, .

As the first General Manager, and later Director-General, Reith had famously said that ‘To have exploited so great a scientific invention for the purpose and pursuit of “entertainment” alone would have been a prostitution of its powers and an insult to the character and intelligence of the people.’ He himself had been influenced by the great Victorian moralist Matthew Arnold, who’d written that a decent, civilized future would only be secured by making ‘the best that has been thought and known in the world’ available everywhere – by making what he called ‘sweetness and light’ prevail. It was no good just cultivating one’s one tastes, Arnold had argued: if the world was to be left ‘better and happier than we found it’, the job was to ‘carry others along’ with you.

For Reith it seemed obvious that in the early twentieth century it was radio, with its ability to reach into every home, regardless of wealth or level of education, that was best placed to make ‘sweetness and light’ prevail. To make sure it ‘prevailed’, Reith was also convinced the ����ý needed to have a monopoly. Only what he called ‘unity of control’ would prevent those with access to the microphone from slipping into ‘inferior ways of doing things’.

Reith’s unshakeable confidence that the organisation he led had all the answers, is on full display in this rarely heard recording from 1967. Reith was being interviewed by Malcolm Muggeridge for a TV profile. Only a few bits of the interview were ever broadcast, but the ����ý Oral History Collection retains of the whole encounter. In this brief extract, Reith has just been asked by Muggeridge if he’d ever been troubled by the ����ý’s monopoly:

It was this strong sense of inherited morality which gave Reith the confidence to assert another of his famous policies:

It is occasionally indicated to us that we are apparently setting out to give the public what we think they need and not what they want, but few know what they want, and very few what they need.

It’s difficult nowadays not to think of such a statement as hugely condescending. But Reith was on to something. Most of us can only choose to ‘consume’ what’s already been made available to us: it’s pretty hard to choose something if we’re not even aware it exists.

The ����ý’s task therefore was to leaven a schedule of familiar and comforting programmes – favourite dance tunes, well-known stories – with a sprinkling of rather less familiar output. Reith’s thinking was this: though we often dislike something when we first come across it, we would, if only we showed a little patience, ‘come to appreciate’ it over time. The idea, in other words, was to be just ahead of public taste – though not so far ahead that the public lost all patience.

Did the approach work? In , Muggeridge asked Reith if he thought that by regularly broadcasting orchestral concerts the ����ý of the 1920s and 1930s really had succeeded in popularizing several of the more obscure works in the classical music canon:

Clearly, Reith was a man of his age and his generation. But this aim of nudging as many people as possible towards a better appreciation of a wider range of culture was an idea sufficiently potent – and sufficiently flexible - to outlast his own turn as Director-General.

In the 1940s, one of his successors, William Haley, talked of the ����ý’s responsibility to ‘develop true citizenship and the leading of a full life’. For Haley, like Reith, people were not to be seen as listening or viewing passively – inert, empty, waiting to be filled up – but as living audiences capable of change and growth.

Haley’s own successor, Ian Jacob, had to take account of the arrival of commercial television in 1955, and its determination to give people exactly what they wanted. His own defence of the ����ý’s role in this new environment was to point out that in many American cities, competition between television stations had ended up creating sameness on the schedule rather than variety. For the ����ý, Jacobs explained, creating programmes was not ‘a question of deciding what is good for the people and denying them much of anything else’; it was ‘a question of remaining in a position to withstand pressure from whatever direction it may come and to be able to steer a steady course in fulfilling the aims of the Charter to inform, educate and to entertain’. In other words, the freedom to plan programmes without constantly worrying about ratings was precisely what guaranteed a schedule that was serendipitous, balanced and varied.

Back in 1945, William Haley had attempted to put all these grand theories into practice by reorganising ����ý radio into a pyramid structure. The Light Programme - crisp and friendly with lots of popular music and easy conversation – would be at the broad bottom, attracting about half the potential national audience. Occupying the pyramid’s middle was the Home Service, which would maybe attract another 40 per cent of the population, and which internal documents defined as follows:

...carefully balanced, appealing to all classes, paying attention to culture at a level at which the ordinary listener can appreciate it; giving talks that will inform the whole democracy rather than an already informed section; and generally so designed that it will steadily but imperceptibly raise the standard of taste, entertainment, outlook and citizenship.

Finally, occupying the pyramid’s glittering summit, and attracting the remaining 10 per cent, there was the new Third Programme, with its fierce commitment to high-class culture.

Reith himself hated the scheme. He thought the Third Programme, in particular, would ‘ring-fence’ culture from the great majority. For Haley, though, the pyramid had to be understood as dynamic and porous. Each layer would overlap. And there would be stepping-stones. If, for instance, the Light Programme broadcast the popular waltzes from Richard Strauss’s comic opera ‘Der Rosenkavalier’, then the Home could play one whole act, and the Third could follow-up with ‘the whole work from beginning to end, dialogue and all’. Each listener would be free to move up and down the pyramid, depending on his or her mood at any given time. And perhaps over time, he or she would also find themselves spending more and more of their week tuned to the Third. Perhaps the British people as a whole would move up through the pyramid, so that after many decades the entire structure would be turned upside down, the majority coming to like ‘the best’ rather than ‘the worst’.

Staff on the ����ý’s factory-floor, understood that if any of this was going to work – if that Reithian ideal of spreading sweetness and light was really going to be maintained – it was vital to resist the spread of rigid divisions between different parts of the broadcasting machine.

Barbara Bray, a senior script editor in Radio Drama during the 1950s and 1960s and a close collaborator with such high-culture figures as the playwright Samuel Beckett, was very much the kind of programme-maker we would expect to defend the purity of the Third Programme’s cultural mission. But, as she revealed in her own contribution to the ����ý’s oral history archive, she, too, was acutely aware of the dangers in assuming the traditional divisions of taste and class were permanent – and determined to keep challenging them:

The ����ý’s attitude towards radio was well-practiced by the time Barbara Bray was commissioning scripts in the 1950s and 1960s. But, when it came to television, all post-war Directors-General faced a much newer phenomenon. Its social effects still seemed uncertain.

William Haley, who presided over the television service’s 1946 re-launch, is widely remembered for being utterly averse to the medium’s qualities. Yet when he was interviewed years later for the ����ý’s oral history archive, he took the chance to offer a more nuanced account of his attitude at the time. The first people he’d put in charge of the television service – Maurice Gorham and Norman Collins – had both put the stress on popular entertainment. He quickly replaced them with the ����ý’s Director of the Spoken Word, the rather more highbrow George Barnes. But, he explained, this unlikely appointment was really a sign of just how seriously he took the medium when it came to its social importance:

It wasn’t only television which tested the ����ý’s commitment to Reithian ideals. The audience, too, was changing. And by the 1960s, it seemed to be changing more rapidly than ever. In his , Reith spoke of a ‘more independent-minded’ younger generation. In the same year he was being interviewed, the ����ý launched its new pop radio station, Radio 1. The Director-General of the time was Hugh Carleton-Greene, a man who’d said when he took over in 1960 that he wanted to ‘open the windows and dissipate the ivory-tower stuffiness’ that clung to parts of the Corporation.

But if the interviews in the ����ý’s oral history archive reveal anything, it is that there were plenty of programme-makers on the payroll who’d been opening windows for themselves without waiting for orders from above. The reason? That Reithian notion of leading public taste rather than just following it - that desire to bring to the public’s attention the new and the unfamiliar – was part of an ethos that had been deeply imbibed for generations. It was why, when the former managing director of ����ý Television, Huw Wheldon, was interviewed in 1978, his abiding impression of the Corporation in the 1960s was the feeling of creative freedom that programme-makers of his own post-war generation enjoyed:

One rising star who’d joined the ����ý during this especially fertile period was the presenter Terry Wogan. And he stayed at the Corporation long enough to witness for himself the swing towards a very different ethos in the 1980s, when Thatcherism was at its height. This was an era when ‘consumer choice’ was championed, and the whole notion of the ����ý ‘knowing best’ seemed suddenly to be a source of embarrassment for the Corporation. When interviewed for the ����ý’s oral history archive in 2002, Wogan was asked to reflect on this dramatic shift – and, in particularly, what seemed to be the final death knell for Reithianism:

There’s little sign in the twenty-first century that the ����ý has lost interest in ‘accountability’. After all, we’re now in an era where even the salaries of its most senior figures are available to see at the click of a mouse.

But, even now, more than a little of the Reithian DNA persists. And what might appear at first to be some kind of stalemate between ‘leading’ and ‘following’ might be better thought of as a carefully calibrated balance in the ����ý’s radio and TV schedules of the ‘popular’ and the ‘improving’, the ‘easy’ and the ‘difficult’, the ‘familiar’ and the ‘unfamiliar’. And perhaps for any public service broadcaster the only answer to the question of whether to lead public taste or follow it is simply this: that it always has to be both.

-

An interview on film totalling over seven hours of footage.

Written by David Hendy, Emeritus Professor, University of Sussex, author of The ����ý: A People’s History.