Like every talent manager at the ����ý, my aim is to make sure this is the place where the most talented people love to work. And that’s talented individuals at every stage of their careers – new talent, developing talent, top talent and then enabling these people to pass their skills on to the next generation of broadcasters.

Easy to say, but of course much harder to realise. And not without its demons. So what a fascinating experience this has been for me, to open up the ����ý oral history archive and hear how the men and women of the past tackled the issue of talent, how they grew celebrity and popular personality on air, how they nurtured the skills of those off-air, and how they made sure there was never an absolute divide between the two.

The Talent Impresario

Bill Cotton was the son of the famous Billy Cotton, band master and impresario. He inherited his father’s flair and nose for show business, knowing instinctively what performers, presenters and artistes he needed in his TV line up, and trusting that instinct absolutely. He seemed to know too that he was inhabiting a glorious moment for the burgeoning TV industry in the 1960s and 70s, with talented people everywhere clamouring to have a go – Morecambe and Wise, Ronnie Corbett and Ronnie Barker, Dave Allen, Mike Yarwood, Cilla Black, Cathy Kirby, Simon Dee, Cliff Richard… He reels off the names in his interview, and admits ‘I was quite good at picking them… what is more important you don’t just have to pick them, you have to pick them when they can do it’.

So Cliff Richard’s agent kept badgering Bill Cotton for a TV series, but Cotton held out until he was sure that Cliff was ready for a Saturday night spectacular – which he eventually went on to front on 3rd January 1970. And it’s not just picking the moment, it’s also knowing what your entertainers are good at – not what they think they are good at. So Cotton disappointed both impersonator Dick Emery and showbiz star Bruce Forsyth when he told them they couldn’t have the singing slots they desired in their shows, but they could absolutely go on doing what they were sublimely good at and what the audiences loved them doing.

These conversations can be very difficult. It can’t have been easy telling Bruce Forsyth he was ‘third-rate doing all that stuff’ (the song and dance routines), but it’s all part of the talent management process. I am sure too that Cotton would have been constantly on the look-out for opportunities for his team of talented personalities– as with Bruce Forsyth and the new Generation Game vehicle (‘this has got Bruce Forsyth written all over it’).

It is all part of helping talented people to shape their ideas, managing the relationship with them over time, and reflecting back to them the broader audience perspective too.

Audience and talent

The needs of our audiences driving our choice of talent was the next striking oral history insight that I encountered. In the mid-1960s, the ����ý had no youth voice on radio. The likes of Radio Luxembourg and the exciting pirates of Radio Caroline – spinning discs illegally on an old oil tanker off the East coast of England – were giving teenagers exactly what they wanted: wall to wall pop records. So what did the ����ý do? They did a talent grab, and when the UK government finally made the pirates illegal in 1967, Robin Scott, the new Controller of ����ý Radio, offered them jobs on the good ship ����ý.

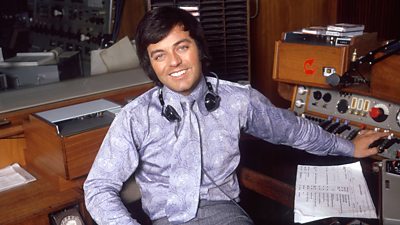

This was the audience telling us who they wanted to hear. When Tony Blackburn came from Radio Caroline to Radio 1, he immediately connected with a younger audience and made them feel the newly created ����ý pop station belonged to them. He did more too – it wasn’t just the people, it was also the technology. Tony Blackburn couldn’t spin his discs and banter his way through the morning show unless he had his self-op desk: the technology was key to his radio fluency and Scott made sure he had all he needed.

The transformation wasn’t easy ‘there was a feeling that Broadcasting House had been invaded… by a rather disreputable crowd’! But all credit to Scott that he realised ‘it was death to the organisation’ unless he brought about this change and satisfied the needs of young listeners.

In the same way today podcasting has enabled so many talented presenters to find a new way of expressing themselves – the format gives them licence to present a different, often more informal version of themselves to how they appear on a scheduled radio programme.

And it’s not just on-air talent. When Michael Peacock was seeking to create the second ����ý channel – ����ý Two in 1963, at age of just 34 - he realised that he didn’t have the right production teams in place. So he initiated a vast recruitment drive – 1,000 new producers, scriptwriters, directors, assistants were appointed, so that the content would be right for a new channel. New voices for a new age. It was bold and brave thing to do. He realised as well that it didn’t just stop at the recruitment, the new ����ý 2 team then had to be appropriately trained, encouraged and developed: he had to create a whole new culture within the fixed culture of the ����ý.

It’s a parallel with what we are doing now in 2022: appointing 1,000 new apprentices. They will have new digital skills, new perspectives, new voices, and they will begin a transformation process much as Peacock aimed to do with his new second channel launched in 1964.

New Talent

One of the best jobs I ever had was producing The Food Programme on Radio 4. And I remember its first presenter Derek Cooper telling me that when in 1979 he initially presented his proposal for a six part pilot, he was asked if he was sure that there was enough to say about food to fill six programmes?! Unbelievable, when you consider the feast of food programming that now spills across our radio and TV schedules.

So when I listened to the recollections of TV cook Zena Skinner talking about her first TV audition, it struck me that it’s ideas as well as people who need to find their moment. That’s a part of the talent quest too.

Zena Skinner’s appointment tapped into the end of post-war austerity, and the emergence of cooking as an everyday act of creativity to an audience of women at home. When she had her TV audition - comically using a few stationery items on a desk - her future producer was checking out if she had both the knowledge the audience needed but also the right practical skills to communicate them on television.

Since the 1970s, the ����ý has been formalising its approach to identifying new talent – especially around young people. In 1978, it launched Young Musician of the Year, which has created the careers of an extraordinary array of classical talent, from Nicola Benedetti to Sheku Kanneh-Mason - both of whom have gone on in turn to promote their own inspiring schemes of musical development.

One of the most recent iterations of these talent programmes is ����ý Introducing which, as Yasser from the Asian Network says here, takes people ‘quite literally from making music in their bedroom to the radio’. It has made the careers of Ed Sheeran, Jake Bugg, Florence and the Machine, among many others, and put their music on ����ý radio stations, offered them master classes with the best in the business, and even propelling them on stage at the Glastonbury Festival.

Now, there is a lot of very useful data behind the search for new talent, and we work closely with our Audiences teams to understand what people want now and in the future. How is current on air talent perceived? Who are we missing? How can we curate a pipeline of talent? How can we use talent to deftly express the changing nature of Britain and its place in the wider world?

But it’s never an exact science and as Bill Cotton knew, it’s instinctive and the human. My job and the jobs of all those in the past whose recollections I’ve listened to here come down to that. At its very best, the quest for talent is the endless search for those unique, original voices which connect us brilliantly with the moment and with all our audiences everywhere.

Written by Dixi Stewart, current Head of Talent Management

Get to know ����ý Music Introducing

Discover how ����ý Music Introducing supports emerging UK artists: from the Uploader to national radio, festival stages and beyond. Artist from the Uploader can now find their tracks being played on ����ý Radio 1, Radio 2, Radio 3, 6 Music, 1Xtra, Asian Network and the World Service. .