India has made huge leaps forward in tackling its sanitation challenges as part of its Clean India Mission in which every household has access to a safe toilet.

And yet, ask anyone what happens to their poo after they flush, and you will be met with a blank expression. 60% of urban Indian homes are not connected to sewerage systems. Instead they are usually linked to septic tanks which should require regular cleaning, or 鈥榙e-sludging鈥�, to remain hygienic. Some lead to open drains, a practice which presents a threat to public health. Therefore, addressing knowledge, attitude and practice around safe containment, disposal and treatment of faecal waste is critical.

In 2017, we were given a new communication challenge by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation: Could we make Faecal Sludge Management (FSM) an issue that is as important to people in urban India as air pollution has become? Could we get people to care about what happens after they flush?

We started with formative research, and while our findings were not particularly surprising, they helped to draw patterns and mine insights about what might help us address this significant challenge.

We identified three segments in the population, based on their actual sanitation practices and their response to the statement 鈥業t is okay to wait to clean/ empty the septic tank until it is full鈥�. Of these, just over one-fifth would desludge their tank proactively, while two-thirds of respondents would desludge only when there is a backup or overflow that prevents them from using the toilet. A full 11% said their tanks were connected to open drains.

Across all three groups, we found that the predominant attitude was to avoid the problem for as long and by any means possible 鈥� by building enormous septic tanks that do not need cleaning in their lifetimes, or by desludging as an emergency measure, once the tank overflows. This was combined with the attitude that it is someone else鈥檚 responsibility 鈥� the sense that an individual household does not create the problem and therefore, should not be responsible for the solution.

The challenge to make it resonate

So how could we make faecal sludge a problem people cannot ignore? How could we overcome the challenge of caring about the common good? How could we make the invisible, visible?

Our objectives were to increase awareness, heighten risk perception and build a sense of urgency. We knew we needed to link faecal sludge to something precious 鈥� and what could be more compelling than a link to water? We needed to make the threat up close and personal.

A poo demon to the rescue

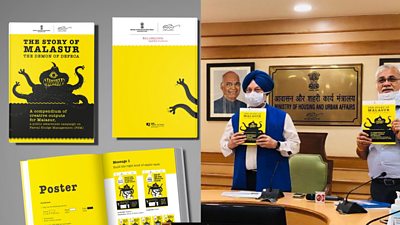

We needed an idea that was insight-driven, user-centric, media agnostic and disruptive. So, we turned to Indian mythology - and to traditional tales of good and evil, of gods and demons. And we created a new demon 鈥� the Demon of Defeca, Malasur. Malasur is an unseen demon who lives under your feet, bubbling away, biding its time, waiting until that opportune moment when it can erupt into a backflow or an overflow. Malasur is a threat to your water unless you build the right kind of septic tank, do regular desludging and keep an eye on where your poo is being dumped.

Malasur spreads its tentacles

We developed a 360 degree campaign using film, radio, outdoor advertising, GIFs, outreach material and a comprehensive toolkit to enable stakeholders (government and non-government) to implement the campaign across different regions and platforms. Despite the pandemic, the Malasur campaign has already been launched by over 115 local bodies in select states in India. In the first two weeks after its launch on social media, the film earned 525,000 impressions on Twitter and was watched more than 300,000 times.

The Malasur campaign has been piloted, pre-tested and evaluated, providing valuable learnings on how to design communication strategies and solutions around FSM behaviours. This is what we found:

- Disruption works. A campaign benefits greatly from a hook that can break through the noise in highly crowded urban landscapes, mass media and social media platforms

- Each piece of content needed to have a singular focus 鈥� faecal sludge is complex, so breaking it down to simple, doable actions was key

- The connection to water was compelling 鈥� faecal contamination of water provides a strong reason to believe - leading to intent and action

- A clear call to action such as a link to a helpline number/ licensed desludging operator added to the credibility of the campaign

- Bespoke implementation plans specific to each city are more useful.

As Faecal Sludge Management becomes increasingly critical in improving the total sanitation landscape of a country, faecal sludge treatment plants are coming up. And we鈥檙e seeing a growing realisation within the water, sanitation and hygiene sector that behaviour change and demand creation are as important to the conversation as infrastructure.

Malasur with its beady eyes and tentacles gives a face to a problem that did not exist in public consciousness. It proves that an idea with depth and character, implemented well, can move the needle towards safe water and healthier citizens.

--

Radharani Mitra is Global Creative Advisor for 大象传媒 Media Action

Learn more about our sanitation projects in India here.