Downloads

Publication date: August 2012

Summary

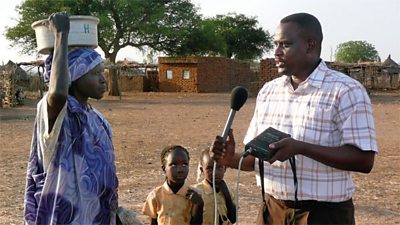

- 大象传媒 Media Action is developing a series of radio programmes that aim to improve Reproductive, Maternal, Neonatal and Child Health (RMNCH) in South Sudan, with funding from the UK鈥檚 Department for International Development.

- This research sought to understand what information and support women and their families might need to keep them and their babies safe before, during and after delivery. The research findings will inform the radio programmes.

- We found that in many cases, women had knowledge and awareness of healthy practices but did not always fully understand what was beneficial about these practices. Additionally, women and their families did not always act on health advice from health workers or health communications if the information went against social or family norms.

Context

Decades of violent civil war and continued unrest have left South Sudan with very little infrastructure, few roads and limited health facilities. The death of over 2 million Sudanese during the war has led to a societal desire for large families, to help replenish the country鈥檚 population. South Sudan also has a strong tribal history and women often face pressures to marry and start having children at an age when their bodies are not fully developed, which often leads to complications. As a result, South Sudan has one of the worst rates of maternal mortality in the world. Young women in the country are three times more likely to die in childbirth, than they are to complete eight years of basic education.

The project

大象传媒 Media Action鈥檚 project in South Sudan aims to improve Reproductive, Maternal, Neonatal and Child Health (RMNCH) through effective use of media and communication. The project will produce radio programming, coupled with community outreach work and training for local language partner stations and NGO/government partners. The project aims to support changes in knowledge, attitudes, norms, self-efficacy and societal support for change around the key health issues that government and civil society have prioritised as critical for saving the lives of women, newborn babies and children.

Research methodology

The research aimed to understand existing levels of knowledge, beliefs and social norms around RMNCH behaviours as well as the barriers and enablers that affect the adoption of recommended health behaviours. 19 focus group discussions were carried out with women of child-bearing age, traditional birth attendants (TBAs) and older women between 40-60 years old. 23 interviews with six categories of participants including husbands, community health workers, hospital or health centre staff, male opinion formers, female opinion formers and government directors for health were also conducted.

Findings

The majority of women who were or had been pregnant did know that they should attend some form of antenatal care (ANC) more than once. However, they were not clear about what ANC really entailed. Many felt that having a TBA check the position of a baby in the last months of pregnancy was adequate and were not aware of any specific number of times that they should attend ANC. Many women felt that they were unable to plan regular ANC check-ups due to responsibilities at home and a lack of money.

Several women involved in the research considered birth a natural process and so did not recognise the need to have a birth plan. In all the areas we visited, participants reported that women prepare the same thing for their delivery, which involves collecting water, firewood and food, cleaning or plastering the walls with mud or other materials and preparing cloths and a razor blade for cord cutting. Beyond this, birth planning was not often recognised as a preparation measure. In some cases, traditional beliefs such as it being bad luck to prepare clothes for a baby before birth were also barriers to women acting on recommended birth planning behaviours.

The importance of delivering in a health facility or seeking a midwife for delivery did not resonate with some women and their families, even if a health worker had told them that it was important for them to do so. Many pregnant women reported that they would only go to a health facility if complications arose at their delivery. Some felt that as women had been delivering babies with TBAs at home for generations, it was fine to continue doing so and others felt the facilities were not accessible to them. Throughout the research however, most participants cited a lack of money or savings as a key barrier preventing them from accessing health services or preparing for birth. As husbands are the key decision makers on whether a woman will be able to buy new things or pay for transport to access services, women often reported that their RMNCH practices were dependent on the financial status and choices of the father.

Women of child-bearing age often felt that they were not able to carry out recommended health behaviours because they were not practical. For example, women of all ages showed a high level of awareness about breastfeeding a baby very soon after birth and about half of the women knew that it was recommended that babies should be breastfed exclusively for the first months of their lives. However, they also reported issues such as delays producing or insufficient breast milk, which meant they supplemented by feeding the baby sugar or salt water and porridge. Women were not aware of methods to overcome breastfeeding issues and did not feel that supplementary feeding would harm the baby.

Across the four states in which the research was undertaken many older women reported that late teens used to be the average age for a first pregnancy but that now, girls are more likely to become pregnant at a younger age, sometimes as young as 12. Modern lifestyle changes such as drinking alcohol as well as earlier marriages were reported as the cause of the trend. Older women expressed disapproval of this change and felt that younger girls could experience more pregnancy complications or be less able to care for their babies.

There were big differences between RMNCH practices in rural and urban locations, whilst tribal influences also affected practices from region to region. In one location with a distinctive tribal heritage, women preferred to squat for the delivery. In other areas, this was thought to be a dangerous practice. The strength and traditions of a husband鈥檚 tribal heritage was also reported as the deciding factor around what traditional practices would be carried out around a birth, such as putting ash on a baby鈥檚 umbilical cord. Additionally, participants felt that women in all urban areas are much more likely to seek formal health care and deliver in a health facility than their rural counterparts.

Implications

We found that local norms, beliefs, attitudes and practical realities are far more likely to influence a woman鈥檚 maternal and child health behaviours than health advice she had been given. Therefore the importance of and reasons behind carrying out healthy behaviours should be emphasised to encourage uptake by the target audience. As RMNCH practices and norms vary so much from region to region, radio content should be tailored to the local context and delivered in local languages.

As older community and family members, especially husbands, have a huge influence on a mother鈥檚 maternal health, programming also needs to focus on these groups. Financial and social barriers to improved health practices should also be addressed by programming. For example if the programme is recommending pregnant women attend four ANC check-ups it should also address how a family can save for and plan for the visits.