ҙуПуҙ«ГҪ's secret World War Two activities revealed

- Published

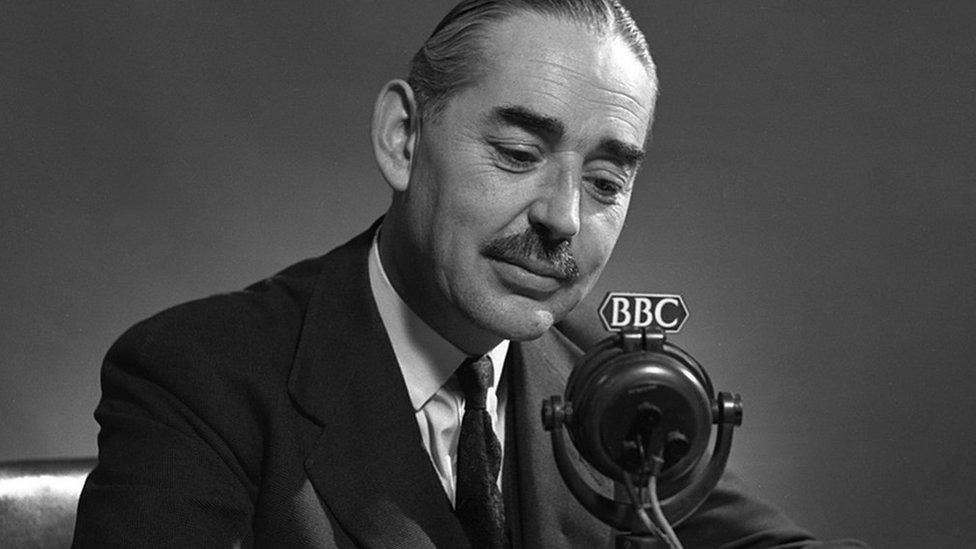

ҙуПуҙ«ГҪ newsreader John Snagge reported on the D-Day landings

A new archive has revealed the ҙуПуҙ«ГҪ's role in secret activities during World War Two, including sending coded messages to European resistance groups.

Documents and interviews, released by ҙуПуҙ«ГҪ History, include plans to replace Big Ben's chimes with a recorded version in the event of an air attack.

This would ensure the Germans did not know their planes were over Westminster.

ҙуПуҙ«ГҪ programmers would also play music to contact Polish freedom fighters.

Using the codename "Peter Peterkin", a government representative would provide staff with a particular piece that would be broadcast following the Polish news service.

A new archive revealed the ҙуПуҙ«ГҪ's role in secret broadcasting activities during World War Two

Historian David Hendy said: "The bulletins broadcast to Poland would be deliberately short by a minute or so and then a secret messenger from the exiled Polish government would deliver a record to be played.

"The choice of music would send the message to fighters."

Alec Sutherland, the man who oversaw the use of music at the end of news bulletins, said it was his job to make sure producers played the right record, even if it was scratched.

"They would see one which they thought would make a better broadcast and the wrong bridge would get blown up in Poland."

The coded messages to the French resistance in news bulletins were less opaque and consisted of a few phrases dropped into a programme script or foreign language news bulletin.

On the night of 5 June 1944, the eve of D-Day, the phrase "Berce mon coeur d'une langueur monotone" or "cradle my heart with a monotonous languor" signalled the invasion was about to begin.

ҙуПуҙ«ГҪ transmitters at Alexandra Palace in north London were also used as part of an RAF operation to distort the navigating system of Luftwaffe bombers, so that they were misled about direction and range.

Other items in the archive include several contemporaneous eye witness accounts of bombing raids of Broadcasting House in 1940 and ҙуПуҙ«ГҪ newsreader John Snagge's account of the hours leading up to his first broadcast about the D-Day landings when he was kept under armed guard to stop the news leaking out.

The full oral history collection, The ҙуПуҙ«ГҪ and World War Two: 100 Voices that made the ҙуПуҙ«ГҪ, is available online at https://www.bbc.com/historyofthebbc/100-voices/ww2

- Published1 September 2019

- Published5 June 2019

- Published10 September 2015