Are Hong Kong’s pink dolphins about to disappear?

It wasn’t until the 1990s that anyone actually counted the number of pink dolphins living off the coast of Hong Kong. Construction of the city’s new international airport, Chek Lap Kok, was almost complete but in the process important dolphin habitat had been reclaimed for runways and terminal buildings. Hong Kong officials decided to check how the dolphin population was doing. They counted 250 individuals.

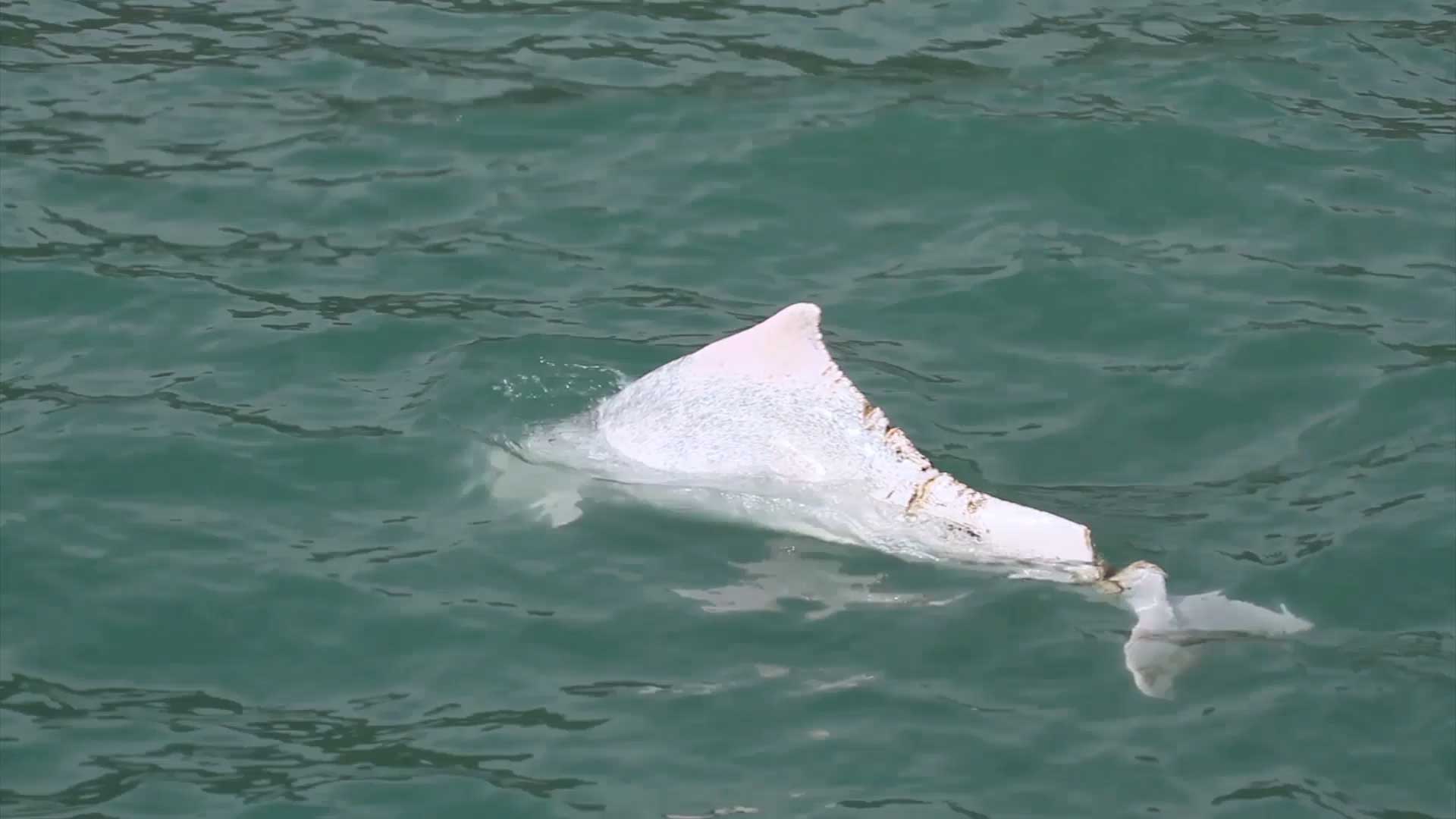

Today only 32 remain

Hong Kong’s pink dolphins are actually Indo-Pacific Humpback Dolphins, or Chinese White Dolphins. And their skin isn’t pink; the animals live in murky waters with little sun penetration so it simply lacks pigmentation. It is warm blood pumping through vessels close to the skin’s surface that gives the dolphins their bubblegum pink appearance.

The first recorded mention of these unusual creatures was by a British man called Peter Mundy in 1637. Mundy, a merchant who helped introduce tea to the UK, described the dolphins as "sword fish", not realising they were mammals. He wrote in his journal: “The porpoises here are as white as milk, some of them ruddy withal.”

Hong Kong’s fishermen have known about the creatures for centuries. They call the dolphins Hak Kei (the Black Taboo) or Pak Kei (the White Taboo). "Once they are here, all the fishes will be gone!" says Uncle Wai, a fisherman in Tai O, a major fishing village in the western edge of the territory.

“Fishing boats don't usually follow where they go. We fishermen mostly hate them.”

Catching a glimpse is not easy but dolphin-watching tours have become popular with tourists. When people see the dolphins for the first time, their joy is obvious.

“I’ve had some striking moments,” says Janet Walker, a senior guide with the DolphinWatch tour. "You know, amazing aerial displays and things… or like the dolphins that come and swim under your feet! Or, you know, look you in the eye.”

But Janet is worried. She’s noticed the dolphins are disappearing. "You know we are still seeing a few calves, but not that many, and the number’s still plummeting."

“I think we are very privileged to see them. Because with the amount of development that is going on around Hong Kong, especially reclamation of the sea, they are going to be gone sooner or later, I think”

Outside of the tourism and fishing industries, pink dolphins aren’t a part of daily life for the 7.4 million people that live in the dense and bustling port of Hong Kong.

"To be frank, like many Hong Kongers, I knew little about the dolphins until I picked up this job,” says Taison Chang, chairman of the Hong Kong Dolphin Conservation Society.

"And that's the problem. Many of us were aware of them, but all we knew was the superficial stuff. We need to know about the problems they are facing before we can conserve them.”

In 2017, the population looked like it was low but stabilising. When the latest figure of 32 dolphins was released last summer, a 32% drop on the 2017-2018 period, it was a shock to conservationists like Mr Chang.

“We knew the figure would keep going down but we never thought that it would drop to just 32”

Chinese White Dolphins can be found off the west coast of Taiwan, as well as Vietnam, Thailand, and as far as Java in Indonesia in the South, and Tamil Nadu in India in the West, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). While this explains why the species as a whole is not yet classified as endangered, what is clear is that their habitat along the Chinese coast has been rapidly shrinking as huge infrastructure projects reclaim marine habitat and the surrounding water becomes busy and polluted. Populations like the one in Hong Kong could disappear within a generation.

Mr Chang groups the threats into four categories:

Coastal development

and reclamations

Marine traffic

Water pollution

Fishing

Dolphin WL212

The story of dolphin WL212 is a tragic example of the threat dense marine traffic poses to the pink dolphins. In 2015, it was found with cuts so deep that its tail was almost severed. It was thought the young six-year-old male was hit by the blades of a boat turbine.

Hong Kong is one of the busiest ports in the world. For the pink dolphins not only is there less space but the habitat available to them is crisscrossed 24 hours a day with thousands of boats.

Taison Chang worked with Daphne Wong, a Hong Kong-born filmmaker, to document what happened to the dolphins. He provided her with video records of Dolphin WL212's final days.

"Back then our team kept tracking it for three weeks. We saw it doing its best to survive despite those heavy injuries, to feed itself," Mr Chang recalls.

After a media outcry, Ocean Park, a marine park owned by the government, captured the struggling dolphin for treatment. They named him Hope. But after four days in captivity, Hope died from his injuries.

The incident left a lasting impression on Mr Chang.

"I’ve been thinking, why was this dolphin hurt so badly? Have we done something wrong? I’ve been thinking a lot about this. How could we protect them? Conserve them?"

“I was editing the film and I was about to cry,” said Daphne.

“We owe the dolphins. We humans destroy the ocean wilfully.”

Daphne Wong

“We owe the dolphins. We humans destroy the ocean wilfully.”

Daphne Wong

Megaprojects like the building of Hong Kong International Airport destroyed chunks of dolphin habitat in the 1990s and over the past decade a bridge has been built connecting Hong Kong to Macau, and onward to China, which cuts right through the remaining space.

The numbers speak for themselves. The building of the bridge began in 2009 when the dolphin population stood at 88 individuals. By the end of the first year of construction, 13 dolphins were dead – a 15% reduction in population size.

“We kept our promise: ‘the Bridge opens, and no dolphins move’,” .

But when it opened in October 2018, the bridge was viewed with wariness by many.

Authorities were criticised over a lack of transparency, industrial accidents were scrutinised and many felt it to be a symbol of China’s encroaching hold on Hong Kong.

The Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macao Bridge Authority, an agency jointly set up by Hong Kong, Macau and Guangdong province governments to build and manage the bridge, claims 945 Chinese White Dolphins lived in Hong Kong and the wider Pearl River Estuary in the 2017-2018 period.

But Angel Lam, an Oceans Conservation Manager with WWF-Hong Kong, says they’ve been unable to secure a copy of the full report to assess its reliability.

"It’s hard for academics up there to carry out their work. Would the government ever let them tell the true, downward figures?" questions Taison Chang.

The 大象传媒 asked the Bridge Authority for a copy of the report but they refused to release it.

"There’s very much an attitude of 'the dolphins will go somewhere else!' They can’t!” says Janet Walker of DolphinWatch.

"They don’t have anywhere else to go. And I don’t think many people appreciate or understand that."

For the dolphins, water to the north lacks salinity and water to the south is too salty.

"Because of what they eat, they are stuck in the area where freshwater meets sea water, and so that means river estuaries," explains Mr Chang. "They would not leave river estuaries for the open water. It’s the same for all humpback dolphins around the world."

Timelapse showing habitat loss due to reclamation projects

Timelapse showing habitat loss due to reclamation projects

“As the environment deteriorates because of reclamation, everything gets worse. Food will be running out. There will be less living space. Pollution will intensify.”

Taison Chang

“As the environment deteriorates because of reclamation, everything gets worse. Food will be running out. There will be less living space. Pollution will intensify.”

Taison Chang

But the threats to Hong Kong’s last surviving pink dolphins keep coming.

Reclamations for Hong Kong’s third airport runway have begun.

"They have now finished building the Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macau Bridge, but so what?" wrote an emotional social media post from a member of the Hong Kong Dolphin Conservation Society.

“Works for that white elephant named the third runway are now in full swing. Is there still any space for the white dolphins to breathe?”

In 2014, the airport authority said the dolphins had “from 39 to 339 sq km” of habitat in which to roam free from the coast of Hong Kong to the mainland. It seems like a wide range but since then that space has shrunk considerably. The planned runway would see 6.5 sq km of coastal habitat reclaimed outright.

"Airport Authority Hong Kong has continued to monitor Chinese White Dolphins abundance, movement and behaviour since the commencement of the Three-runway System Project construction," the Airport Authority told the 大象传媒, "to ensure any impacts from the 3RS Project construction works are not having any unacceptable, adverse impact on the dolphins during different work phases."

The Airport Authority claims that measures such as avoiding percussive piling during construction and speed limits for high speed ferries connecting to the airport have been put in place to protect the dolphins.

But their figures also state there were 77 pink dolphins living in Hong Kong in 2018 - more than double the figure of 32 dolphins from the government-sanctioned survey published in August.

And so far in 2019, Ocean Park has found six dead pink dolphins in Hong Kong waters, two of them in or near the reclamation site of the third runway.

With 32 individuals left, every death pushes the Hong Kong population further towards extinction.

"We are at a crossroads," says Mr Chang. He wonders if people even care. "The situation is so bad now. Would the government or even Hong Kongers in general be that determined to protect just these dozens of Chinese White Dolphins?"

“This battle is hard to fight, and it’s a long one, but we have to carry on.”

CREDIT

Author: Martin Yip

Editors: Charlotte Pamment, Samanthi Dissanayake

Online production: Mayuri Mei Lin

Illustrations & graphics: Davies Surya & Arvin Supriyadi

Photos & videos: Martin Yip, Wei Wang, Chi Lok Cheung, Daphne Wong, Matt Jarvis, Hong Kong Cetacean Research Project, Ken Fung (Dolphinwatch), Getty Images

Maps: PlanetLabs, Google Earth Timelapse (Google, LandSat, Copernicus)

Marine traffic data provided by

Publication date: 24 April 2020