Seeds of life:

The plants suited to climate change

Experts at Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, selected 11 seeds from plants and trees that may be better suited to climate change than other species.

Using a scanning electron microscope, artist Rob Kesseler created striking colourised images of the seeds in extraordinary detail.

The five experts at Kew in London chose the species based on characteristics such as resilience to drought and diseases, and suitability to increased global temperatures.

Eleanor Wilding, a technical officer in the Crop Wild Relatives Project at Kew, chose the Daucus carota, the wild relative of the carrot.

Kesseler produced an image of the seed magnified 30 times to reveal a spiky star-like shape, and coloured it with an orange hue.

Daucus carota seed, magnification 30X

Daucus carota seed, magnification 30X

Daucus carota originated on the Iranian Plateau - which includes Afghanistan, Pakistan and Iran - but now grows across much of Asia and Europe.

Seed samples were sourced from Kew's Millennium Seed Bank (MSB) in Wakehurst, West Sussex, home to more than two billion seeds from 39,000 species. “We have Daucus carota growing on the edges of fields in Wakehurst at the Millennium Seed Bank,” says Wilding.

Daucus carota seen in the wild

Daucus carota seen in the wild

The species is the wild relative of the carrot we are familiar with from supermarkets. “The best analogy we can use is how a wolf and a dog are related, so the Daucus carota is like the wolf and the carrot you buy in the shops is the dog.”

The Daucus carota is inedible, looks very different to the bright orange commercial carrot, but has the distinctive sweet carrot smell.

The roots of the Daucus carota

The roots of the Daucus carota

It has its original genetic make-up, making it tougher than cultivated strands and able to withstand harsh growing conditions. It may hold genetic traits that are useful in cultivating a new species of edible carrot which can better withstand drought and warmer temperatures.

Scientists predict that we are on course for the global surface temperature to exceed an increase of 1.5C by the end of the 21st Century, relative to the pre-industrial age of 1850.

Some prediction models in a 2014 report by the United Nation's Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) say that the temperature increase will actually exceed 2C, unless unprecedented change occurs within human societies.

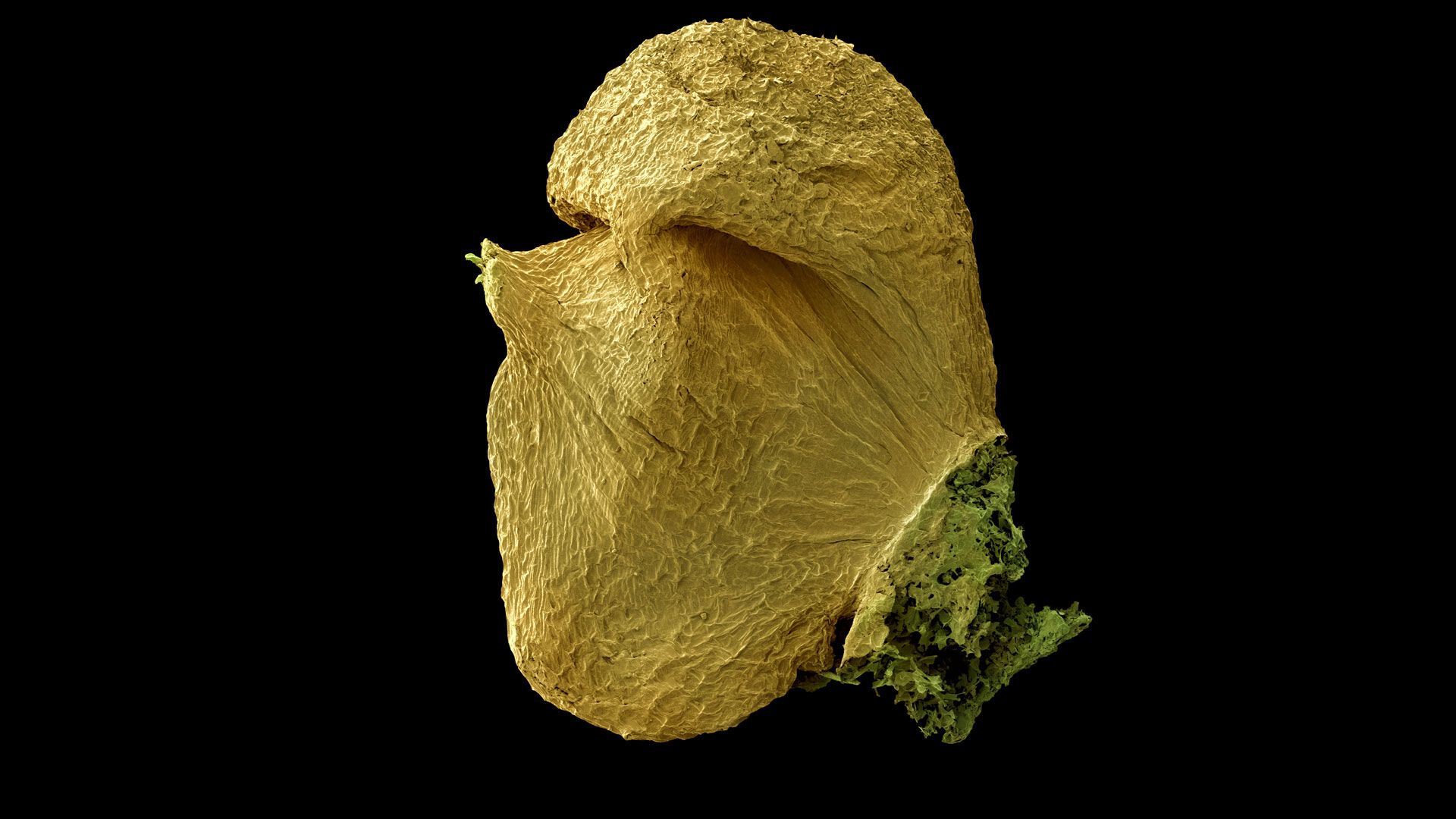

Wilding also chose the Musa acuminata seed. It is viewed as one of the ‘original bananas’ of the plant world.

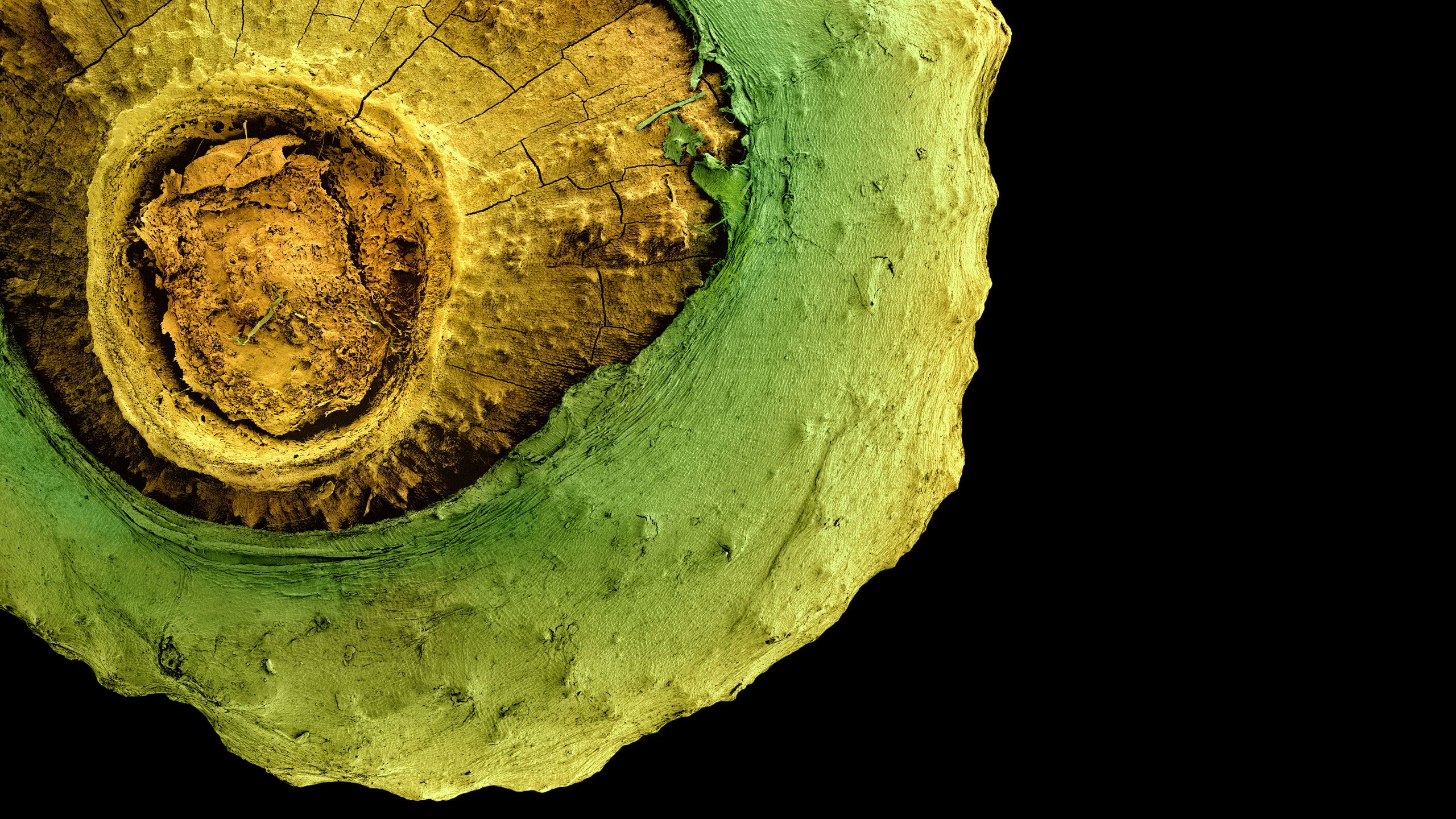

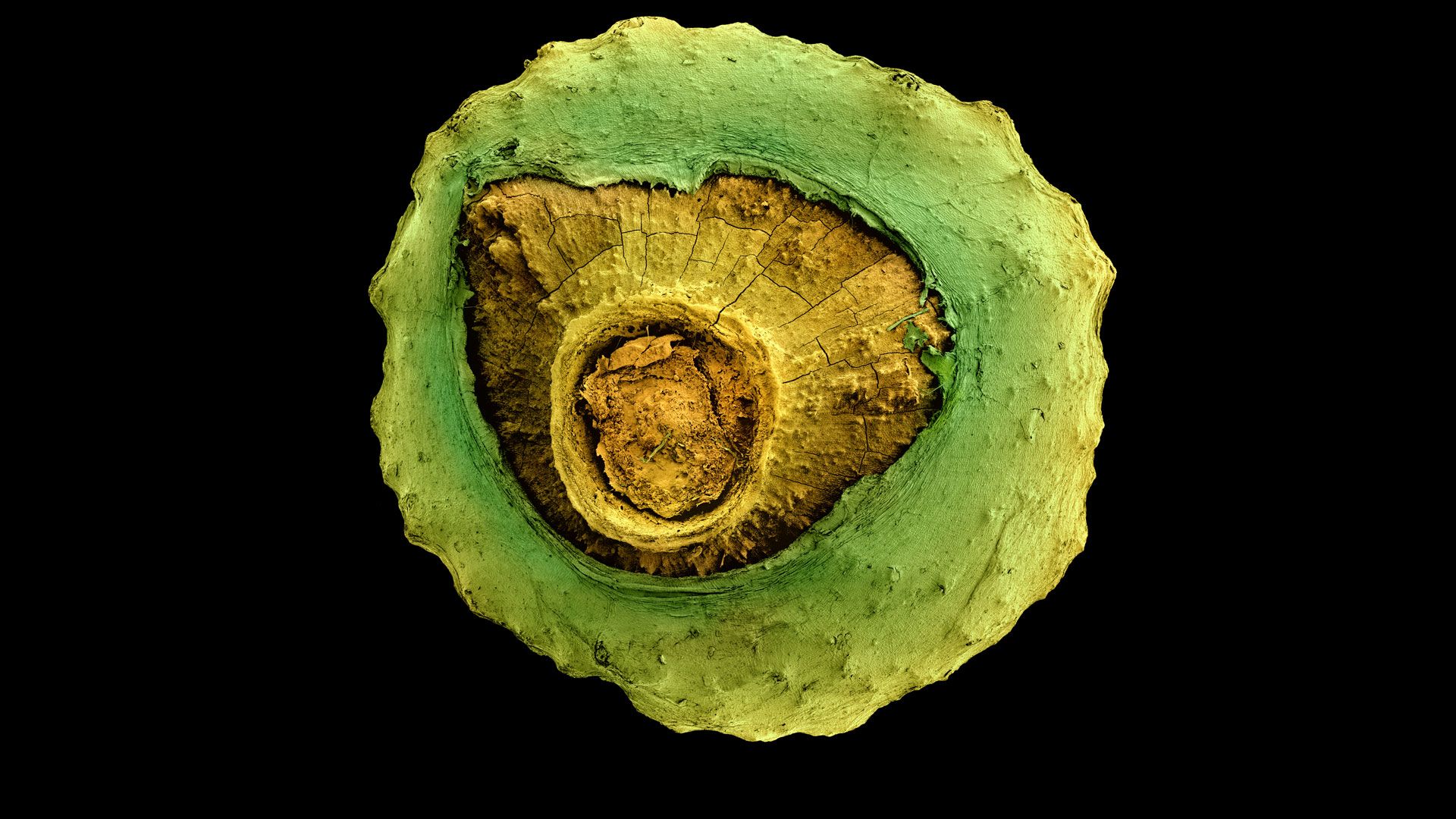

Musa acuminata seed, magnification 45X

Musa acuminata seed, magnification 45X

The wild species has seeds, while the bananas in our food shops don't. Shop bananas are dependent on vegetative propagation, which is where a new plant grows from a previous plant, making them genetically identical. Their lack of genetic diversity makes them susceptible to pests and diseases.

Kesseler chose to colour the seed with shades of green and yellow to reflect the lifespan of the fruit. He says: "As the banana develops, it metamorphoses through a range of colours, from dark to light green and from yellow to brown."

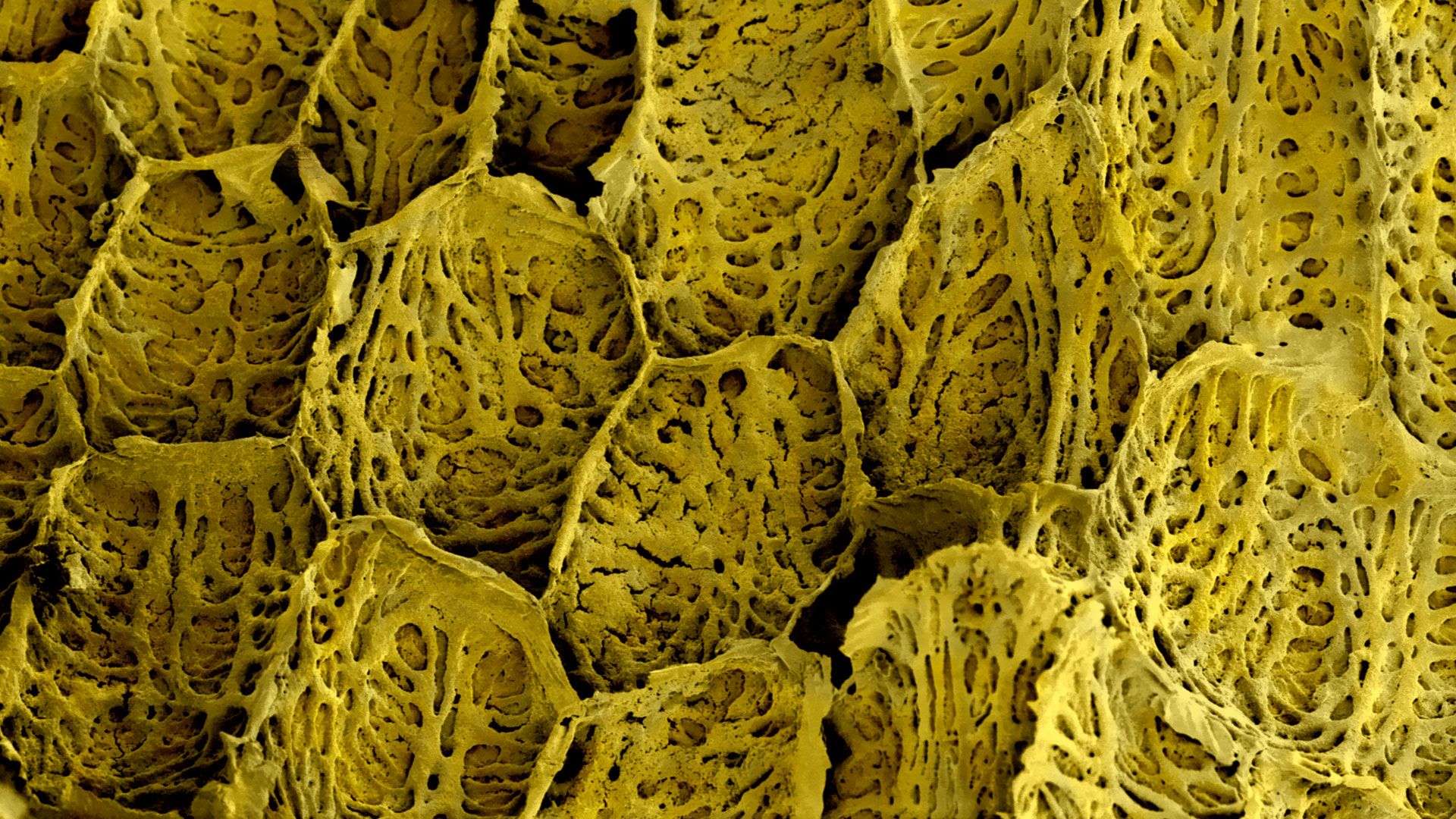

When magnified 1,500 times, the surface of the seed reveals an intricate latticed pattern.

Musa acuminata seed surface, magnification 1500X

Musa acuminata seed surface, magnification 1500X

The Cavendish banana is the most common species of banana eaten by humans, but it is vulnerable to something called Panama disease, which killed off the popular Gros Michel banana in the 1950s.

However, the world’s favourite banana has been under threat from the disease since the 1980s. The race is on to develop a new strain.

Genetic characteristics from the Musa acuminata, such as resistance to Fusarium wilt fungal disease and black Sigatoka leaf spot disease, may prove vital for future banana production and global food security.

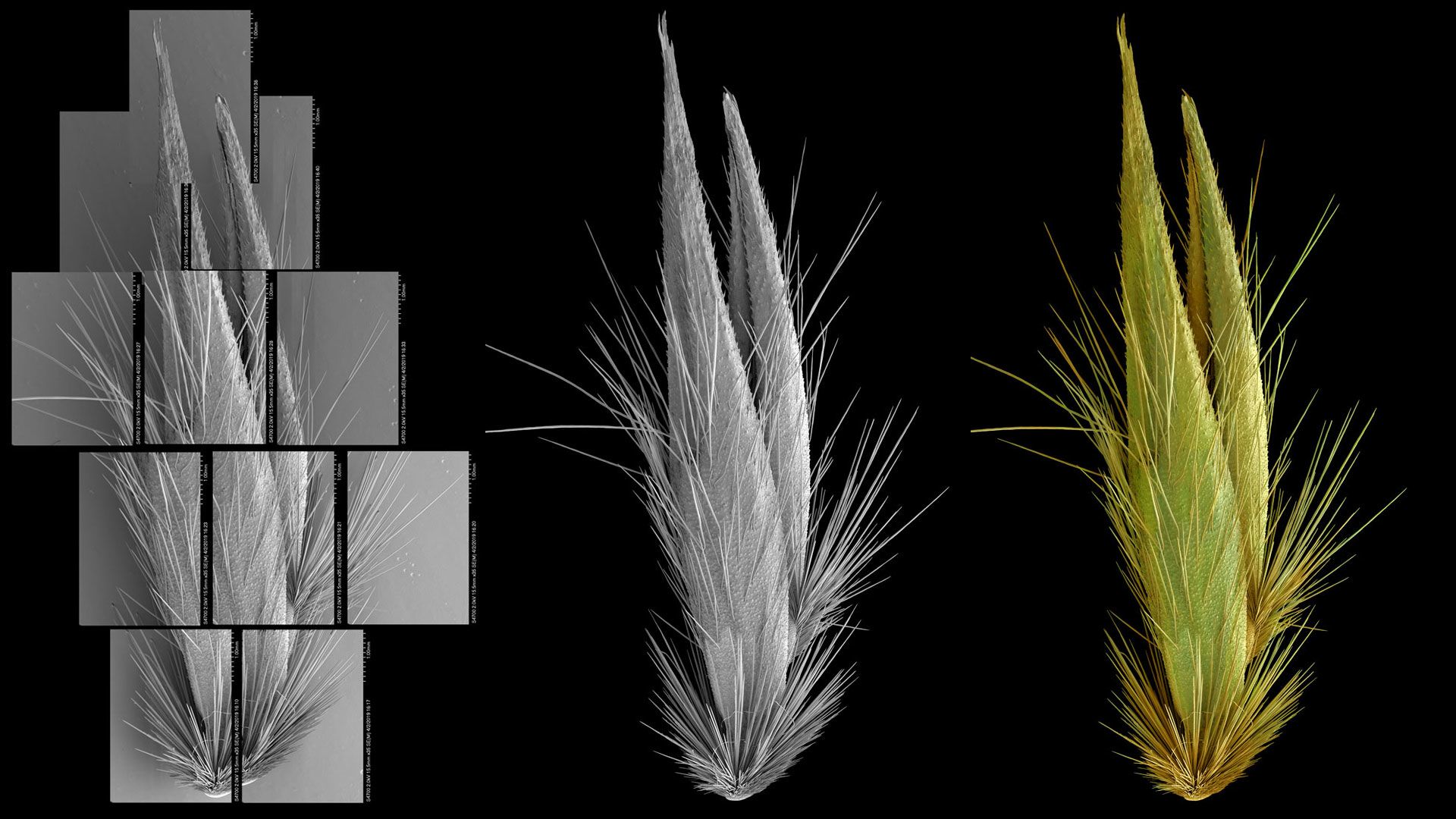

Avena fatua seed, magnification 35X

Avena fatua seed, magnification 35X

Wilding also chose the plant Avena fatua, which the image shows has fine hairs across its surface.

It may be inedible for humans, but it is the ancestor of the food staple oat, which has been feeding people for thousands of years. The plant species is resistant to a number of diseases that can strike down cultivated oat crops.

When magnified 2,000 times, the seed sample revealed a pollen from another plant attached to its surface, with a pollen tube growing from the centre.

Pollen seen on the surface of an Avena fatua seed, magnification 2000X

Pollen seen on the surface of an Avena fatua seed, magnification 2000X

Wilding says: “The Avena fatua can be toxic to surrounding plants, but the traits within can be bred and crossed with cultivated crops, making them more resilient to climate change.”

As a technical officer for the Crop Wild Relatives Project (CWR) at Kew, Wilding is involved in coordinating the collection of seeds and distributing them to international gene banks. The gene banks then isolate desired genetic traits (such as disease resistance) to improve domesticated varieties.

“It’s hard to make [this] mainstream, because the crops are expensive and the challenge is making it something that can be used on a wide scale,” Wilding says.

Wilding also chose Triticum monoccoccum for their tolerance to extreme conditions of drought and heat, and their resistance to pests and diseases. Also known as Einkorn wheat, it is the first cultivated variety of wheat and is originally from Turkey and the Caucasus.

Triticum monoccoccum seed, magnification 35X

Triticum monoccoccum seed, magnification 35X

Medicago rotata is a wild relative of the Medicago Sativa plant, used as a high-protein crop to feed livestock.

Medicago rotata seeds, magnification 40X

Medicago rotata seeds, magnification 40X

Wilding says that climate change is projected to stress Medicago sativa production in areas where the crop is most important, such as the desert regions of Central Asia and Northern Chile.

As water becomes scarcer in these regions, the development of an improved, drought tolerant variety, such as Medicago rotata, will be essential.

At a magnification of 600X, the surface of the Medicago rotata seed shows an uneven dappled texture.

Medicago rotata seed surface, magnification 600X

Medicago rotata seed surface, magnification 600X

Aegilops tauschii, another important wheat relative that exhibits hardy characteristics, is also referred to as rough-spike hard grass. It is found in temperate Asia and the Caucasus region of Russia, Georgia, Azerbaijan and Armenia.

Aegilops tauschii seed, magnification 35X

Aegilops tauschii seed, magnification 35X

“Agriculture is facing huge problems in relation to climate change," says Wilding. "In terms of crop domestication and reduced genetic diversity, but also through crop yield [agricultural output] as a result of climate change."

Dr Aaron Davis is the senior research leader in Kew’s plant resources team, and has specialised in the research of coffee plants for more than 20 years.

He highlights the seed of the plant Coffea humbertii, a coffee crop species originally from Madagascar.

Coffea humbertii seed, magnification 40X

Coffea humbertii seed, magnification 40X

Dr Davis describes Coffea humbertii as a supremely dry-adapted coffee that can take drier and hotter conditions than most other coffee species. He says: “In an era of accelerated climate change it’s a species that we need to research and preserve."

Coffee is a multi-billion dollar industry, says Dr Davis, with the UK cafe sector worth £10bn alone. It is estimated that every day two billion cups of coffee are consumed across the world, with one hundred million people engaged in coffee farming to meet this global demand.

With challenging times ahead for agriculture, should coffee be a priority? No, according to the Swiss government which, in April 2019, put an end to its emergency stockpile of coffee, declaring that it is “not essential” for human survival.

Dr Davis has a slightly different view. “You could say that we could do without coffee in 100 years' time, and we probably could, but that leaves millions of farmers looking for alternative sources of income.

“Plus coffee is an important crop for society, for social bonding, not just in Europe and America but in many parts of the world. Coffee is a really strong part of Ethiopian culture; it is embedded in their daily lives."

The implications of climate change on agriculture in Africa are stark. Dr Davis says that temperatures in Ethiopia have risen on average a third of a degree Celsius per decade since the 1960s. "This is already impacting coffee farming in Ethiopia, with many farmers experiencing reduced yields or sometimes no yearly crop production at all."

A magnification of 3,000X of the Coffea humbertii seed shows what look like fungicidal spores on the surface.

Spores seen on the surface of a Coffea humbertii seed, magnification 3000X

Spores seen on the surface of a Coffea humbertii seed, magnification 3000X

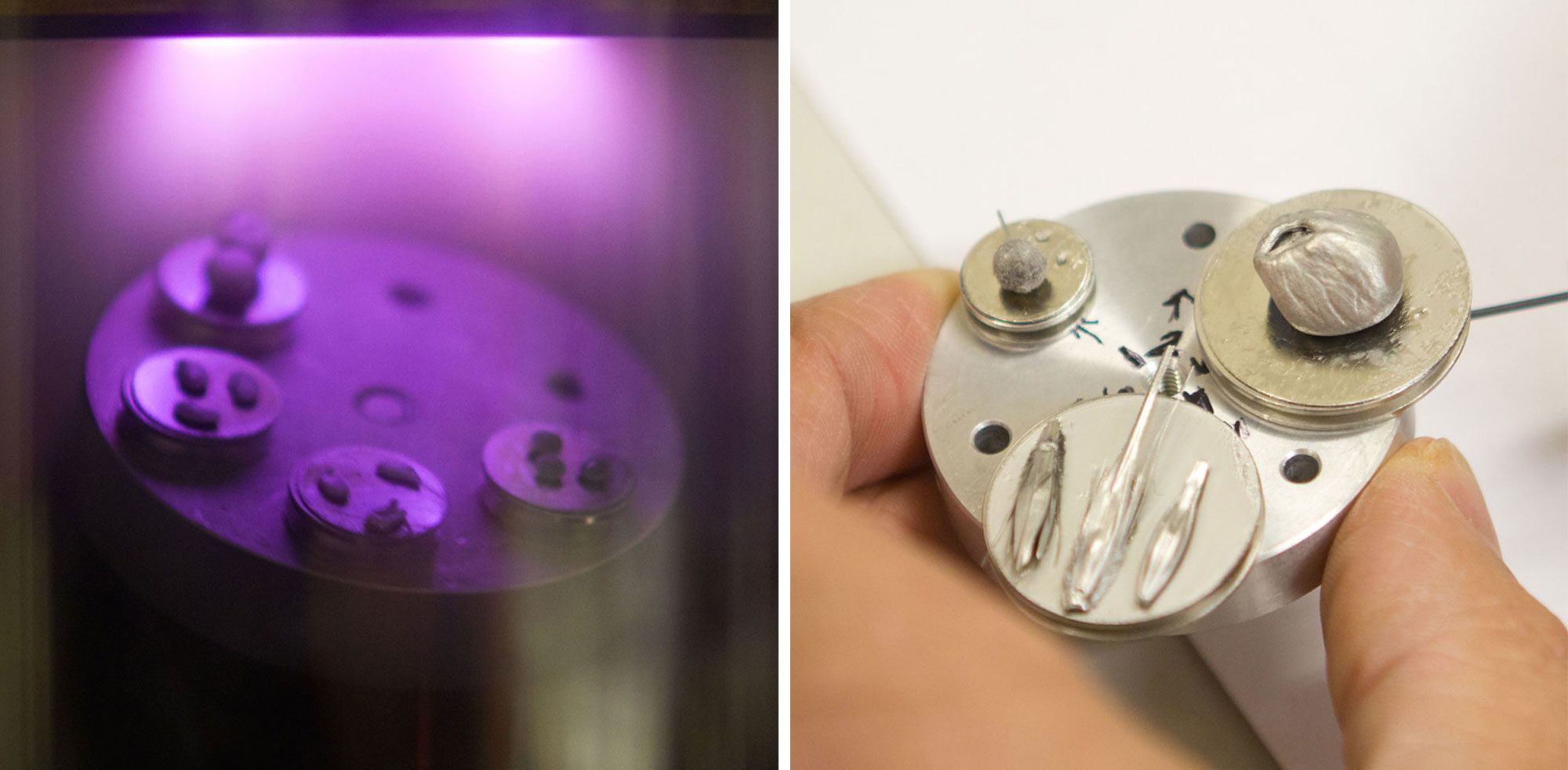

For Kesseler to create these striking microscope images, the seeds had to be sprayed with platinum. The thin coating of metal allows fired electrons to bounce off the surface smoothly and be detected by the microscope.

The images show sections of the seeds magnified in fine detail, with patterns on the surface visible when magnified thousands of times.

Kesseler used software to "stitch" images together, then colourised the image to show depth and detail. An example of the process is seen below.

The artist has explored the creative potential of microscopic plant material with botanical scientists at Kew for more than 10 years.

Artist Rob Kesseler, ambassador for the Royal Microscopical Society and professor at Central Saint Martins college, seen with the SEM at Kew's Jodrell Laboratory

Artist Rob Kesseler, ambassador for the Royal Microscopical Society and professor at Central Saint Martins college, seen with the SEM at Kew's Jodrell Laboratory

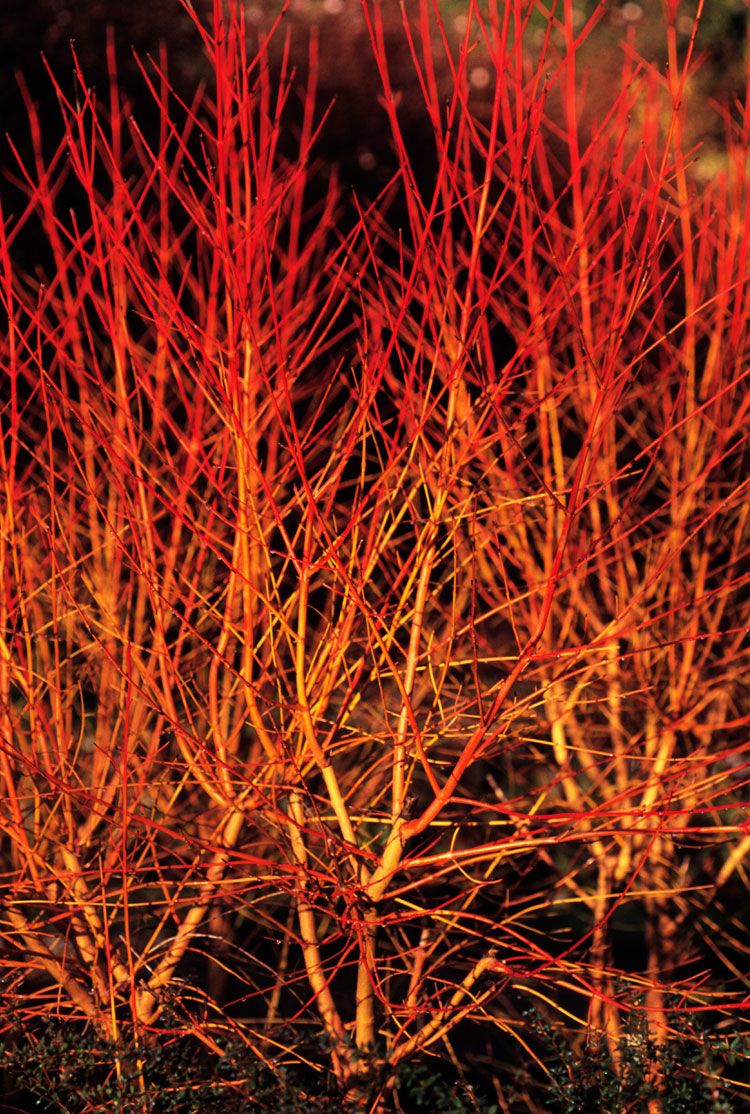

Two seeds of species that are found in the UK were selected by Dr Alice Hudson, a project officer for the UK National Tree Seed Project. She chose the Cornus sanguinea, a small deciduous shrub, and the Tilia cordata, a tree found in ancient woodland.

Cornus sanguinea seed, magnification 35X

Cornus sanguinea seed, magnification 35X

Cornus sanguinea is native to England, Wales and some parts of southern Scotland, and is found growing wild on the edges of forests and in hedgerows.

It is often used as an ornamental plant and is popular in winter gardens for its vibrant and autumnal red stems. Its common name is dogwood.

Cornus sanguinea, known as dogwood

Cornus sanguinea, known as dogwood

Dogwood can cope with moderate drought and does well in a variety of soils, making it one of a number of plants predicted to do well under climate change.

The UK National Tree Seed Project focuses on making genetically representative seed collections for native tree species across the UK. Since starting in 2013, the project has stored more than 10 million seeds, including over 45,000 dogwood seeds and 20,000 seeds from Tilia cordata trees.

“Capturing as much genetic diversity within our seed collections is really important as this is the basis for trait variation, which is an important factor for the survival of species against pests and diseases or under future climate change,” says Dr Hudson.

Tilia cordata seeds and bracts, collected by the UK National Tree Seed Project at Kew Gardens

Tilia cordata seeds and bracts, collected by the UK National Tree Seed Project at Kew Gardens

Tilia cordata, commonly known as a small-leaved lime tree, is native to England, Wales and much of Europe. Once a dominant tree, it is now less widespread and is considered an indicator of ancient woodland. A modern hybrid version of small-leaved lime and large-leaved lime is often found in parks.

Tilia cordata seed, magnification 110X

Tilia cordata seed, magnification 110X

Fertilisation of Tilia cordata only happens in temperatures above 15C, when the pollen tubes can form, so the tree tends to thrive better in warmer southern areas of the UK. So, with rising temperatures from climate change, the tree would prosper in typically colder parts of the UK.

Tilia cordata fruit, magnification 35X

Tilia cordata fruit, magnification 35X

The flowers from Tilia cordata provide a source of nectar and pollen for insects, particularly honey bees, making it an important species for our eco-system.

Flowers from a Tilia cordata tree

Flowers from a Tilia cordata tree

Its wood is not suited to construction as it tends to rot, but its softness makes it ideal for carving and furniture making. The revered 17th Century woodcarver Grinling Gibbons produced a number of famous works using Tilia cordata, some of which can be seen in Saint Paul’s Cathedral in London and Dunham Massey Hall in Cheshire.

A woodcarving by Grinling Gibbons from 1671 depicting the Crucifixion, found in Dunham Massey Hall, Cheshire, UK

A woodcarving by Grinling Gibbons from 1671 depicting the Crucifixion, found in Dunham Massey Hall, Cheshire, UK

Dr James Borrell, a Research Fellow in Kew’s Natural Capital & Plant Health department, chose a seed from the Ensete ventricosum plant, also known as "the tree against hunger".

Ensete ventricosum seed, magnification 40X

Ensete ventricosum seed, magnification 40X

Similar in appearance to a type of banana plant, Ensete ventricosum is actually completely different, earning itself another nickname of "the false banana".

Dr Borrell says: “All of the bananas and plantains you’re familiar with are from one genus [one botanical group of species].

“A few tens of millions of years ago, another group split off and they’re called the ensetes. They produce what look like bananas, but they have huge seeds inside and not much flesh. People actually eat the whole plant."

A villager in her field of Ensete ventricosum in Gibi village, Gurage, Ethiopia

A villager in her field of Ensete ventricosum in Gibi village, Gurage, Ethiopia

A wild version of the plant grows throughout much of East and Southern Africa. Around 5,000 years ago in Ethiopia a palatable variety was domesticated so it could be eaten. Today, enset is only grown in subsistence farming and traded at local markets.

So, how has the Ensete ventricosum earned the grandiose title of "the tree against hunger"? “Enset is very unusual in that you can plant and harvest it at any time of year, and it keeps growing and getting bigger and bigger, so it gives you food security," says Dr Borrell.

The enset is an imposing plant standing at up to 10m tall and 3m in circumference, providing staple food for 20 million Ethiopians.

Ensete Ventricosum plants seen in Gurage, Ethiopia

Ensete Ventricosum plants seen in Gurage, Ethiopia

Eating an enset is not as straightforward as eating a banana. Dr Borrell says: “It’s incredibly complicated to prepare the food and there’s a huge amount of associated indigenous knowledge. It’s one of the things we’re trying to understand at Kew.

“You harvest the whole plant, mashing the pseudo-stem and the underground root into a pulp. You then ferment it in a two-metre-wide pit in the ground for several months, then you bake it into a kind of flat bread called kocho.”

A villager prepares kocho made from Ensete ventricosum, or the false banana tree, in Hayzo Village, Arba Minch, Ethiopia

A villager prepares kocho made from Ensete ventricosum, or the false banana tree, in Hayzo Village, Arba Minch, Ethiopia

When considering climate change, Dr Borrell doesn’t view it as the only environmental issue we should be confronting.

“You have got the big loss of natural habitats, you have over-exploitation of resources, you have climate change, and then you’ve got environmental stresses like pollutants. So you have four things, all coming at the natural world in different directions."

Dr Tiziana Ulian, senior research leader in Kew’s diversity and livelihoods team, has worked on a book detailing why certain trees and shrubs are useful to humans and how to conserve and cultivate them. She describes it as a "recipe book".

One of the featured trees is the Senegalia senegal, known as Arabic gum, which is widespread in Africa and also occurs in Oman, Pakistan and India. The seed is seen under the microscope here.

Senegalia senegal seed, magnification 35X

Senegalia senegal seed, magnification 35X

Seeds from Arabic gum develop inside a pod that opens and drops the seeds to the ground when mature, where they grow or get eaten by animals and then dispersed.

“Arabic gum grows in a semi-arid and arid zone,” says Dr Ulian, “making it a species that can withstand conditions of climate change.”

Arabic gum tree seen in Mauritania in north-west Africa

Arabic gum tree seen in Mauritania in north-west Africa

As well as its hardiness, Dr Ulian believes the many practical uses of Arabic gum make it an important tree now and in the future. The gum that bleeds from the bark of the tree as a defence mechanism when wounded is used as a food additive around the world, notably as the coating of pills in the pharmaceutical industry. It is also used in fizzy drinks as an ingredient that stops sugar crystallizing. In Kenya, it is mainly collected by women and children and is an important source of income for their families.

Pieces of hardened gum arabic

Pieces of hardened gum arabic

On a local level, Arabic gum is used in traditional medicine, and the seeds are eaten by humans throughout the arid region of East Africa. It is also a source of fuel and charcoal.

Dr Ulian warns of the cost of underestimating climate change: “Prevention is the best way to tackle climate change. Once you destroy species you will find that there are predicted changes as a result, but there are also unpredicted changes, so you end up with a bill that is higher than what you expected.

“You need to give people an incentive to protect plant species at the local level, but also at the global level.”

Author: Matthew Tucker

Photographer:

Additional Images:

Image of Daucus carota seed from the book ‘Fruit: Edible, inedible and incredible’ by Wolfgang Stuppy and Rob Kesseler, published by Papadakis

Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

Alamy

Editor: Kathryn Westcott

Publication date: 8 July 2019