The Mangrove Nine

Echoes of black lives matter from 50 years ago

It was a summer Sunday afternoon and most locals were home. Curtains twitched and front doors opened. Some residents ventured bravely outside to witness the scene.

Their quiet backstreet in west London had become a battleground.

At a noisy but otherwise peaceful march to protest at “police harassment” of black people, fighting between protesters and police had broken out.

Nine people would end up at the Old Bailey in a high-profile, but now much-forgotten, trial that secured an important spot in the timeline of black British people.

This article has imagery of a pig’s head which some readers may find upsetting.

Frank’s place

In March 1968 a new all-night restaurant - the Mangrove - opened on All Saints Road in Notting Hill.

Run by Trinidadian-born entrepreneur, Frank Crichlow, it was dimly lit with black leather furniture.

Woman outside the Mangrove restaurant

“I remember when it started. Frank wanted it to be an upmarket restaurant. They played soul music and the waiters and waitresses dressed in white suits and straw hats,” says one of Frank’s friends, 79-year-old Clive Phillip - or “Mashup” as locals call him.

Notting Hill in the late 1960s was not the sought after address it is today.

There were still undeveloped bomb sites from World War Two, many of the impressive white-rendered Victorian mansions had seen better days and an elevated concrete artery - the Westway motorway - was under construction, carving the area in two.

But because accommodation was cheap, many Windrush migrants - people arriving in the UK between 1948 and 1971 from Caribbean countries - called the area home.

Frank’s place

In March 1968 a new all-night restaurant - the Mangrove - opened on All Saints Road in Notting Hill.

Run by Trinidadian-born entrepreneur, Frank Crichlow, it was dimly lit with black leather furniture.

“I remember when it started. Frank wanted it to be an upmarket restaurant. They played soul music and the waiters and waitresses dressed in white suits and straw hats,” says one of Frank’s friends, 79-year-old Clive Phillip - or “Mashup” as locals call him.

Woman outside the Mangrove restaurant

Notting Hill in the late 1960s was not the sought after address it is today.

There were still undeveloped bomb sites from World War Two, many of the impressive white-rendered Victorian mansions had seen better days and an elevated concrete artery - the Westway motorway - was under construction, carving the area in two.

But because accommodation was cheap, many Windrush migrants - people arriving in the UK between 1948 and 1971 from Caribbean countries - called the area home.

“The Mangrove was the ‘go to’ place for black people in the area,” says Barbara Beese, one of the Mangrove Nine.

She vividly remembers the spicy aroma of West Indian food wafting through the restaurant and the mural of mangrove trees on the wall.

“Frank used to make the most wicked pineapple punch. My son was weaned on that juice,” she says.

Barbara Beese

The Mangrove served the best Caribbean food in the area, says Clive - who loved the spring chicken with rice and peas, followed by banana fritters.

Maybe that was why it attracted an impressive array of A-listers.

“Bob Marley would play football around the corner, or be at the music studio, and then pop over to the Mangrove for food,” says Clive.

Jimi Hendrix, Diana Ross and Marvin Gaye - plus actress Vanessa Redgrave - all sampled the cuisine.

But the Mangrove was, say Clive and Barbara, more than just a restaurant. It became a home from home for the Caribbean community - and a space for political discussion.

When Clive arrived in “dismal and cold” London from Trinidad, he struggled. Low on money, unable to find work at the start, and fearful of white racist “Teddy Boy” thugs - he longed for community.

Then the Mangrove opened and he felt at home.

Clive Phillip

“It was like a sanctuary. It was family, a base of support.”

Barbara agrees.

“There was good food, but there was way more to it. All Saints Road and the Mangrove were popularly known as ‘the frontline’.

“People associate that term with drug dealing, but what I mean is that the Mangrove was the frontline of support for the black community.

“They’d get advice on things like housing. Frank’s restaurant became the crucible for all of that.”

But in December 1969, two days before Christmas, the restaurant was dealt a blow. The local council - Kensington and Chelsea - suddenly withdrew Frank’s licence to operate as an all-night cafe.

The Mangrove had been open from 18:00 to 06:00 - with the bulk of trade after midnight. Frank was told he could now only offer takeaway food after 23:00.

He complained, claiming to be the victim of unlawful discrimination.

“The Mangrove was the ‘go to’ place for black people in the area,” says Barbara Beese, one of the Mangrove Nine.

She vividly remembers the spicy aroma of West Indian food wafting through the restaurant and the mural of mangrove trees on the wall.

“Frank used to make the most wicked pineapple punch. My son was weaned on that juice,” she says.

Barbara Beese

The Mangrove served the best Caribbean food in the area, says Clive - who loved the spring chicken with rice and peas, followed by banana fritters.

Maybe that was why it attracted an impressive array of A-listers.

“Bob Marley would play football around the corner, or be at the music studio, and then pop over to the Mangrove for food,” says Clive.

Jimi Hendrix, Diana Ross and Marvin Gaye - plus actress Vanessa Redgrave - all sampled the cuisine.

But the Mangrove was, say Clive and Barbara, more than just a restaurant. It became a home from home for the Caribbean community - and a space for political discussion.

When Clive arrived in “dismal and cold” London from Trinidad, he struggled. Low on money, unable to find work at the start, and fearful of white racist “Teddy Boy” thugs - he longed for community.

Then the Mangrove opened and he felt at home.

Clive Phillip

“It was like a sanctuary. It was family, a base of support.”

Barbara agrees.

“There was good food, but there was way more to it. All Saints Road and the Mangrove were popularly known as ‘the frontline’.

“People associate that term with drug dealing, but what I mean is that the Mangrove was the frontline of support for the black community.

“They’d get advice on things like housing. Frank’s restaurant became the crucible for all of that.”

But in December 1969, two days before Christmas, the restaurant was dealt a blow. The local council - Kensington and Chelsea - suddenly withdrew Frank’s licence to operate as an all-night cafe.

The Mangrove had been open from 18:00 to 06:00 - with the bulk of trade after midnight. Frank was told he could now only offer takeaway food after 23:00.

He complained, claiming to be the victim of unlawful discrimination.

Call to action

One of the reasons given to Frank for his licence removal was that “people with criminal records, prostitutes, and convicted persons” used the Mangrove.

“My restaurant is patronised by respectable people,” wrote Frank on the Race Relations Board complaint form. He also said his premises had been “unlawfully raided” by police on two occasions.

With his new restricted licence, Frank felt he was under close scrutiny.

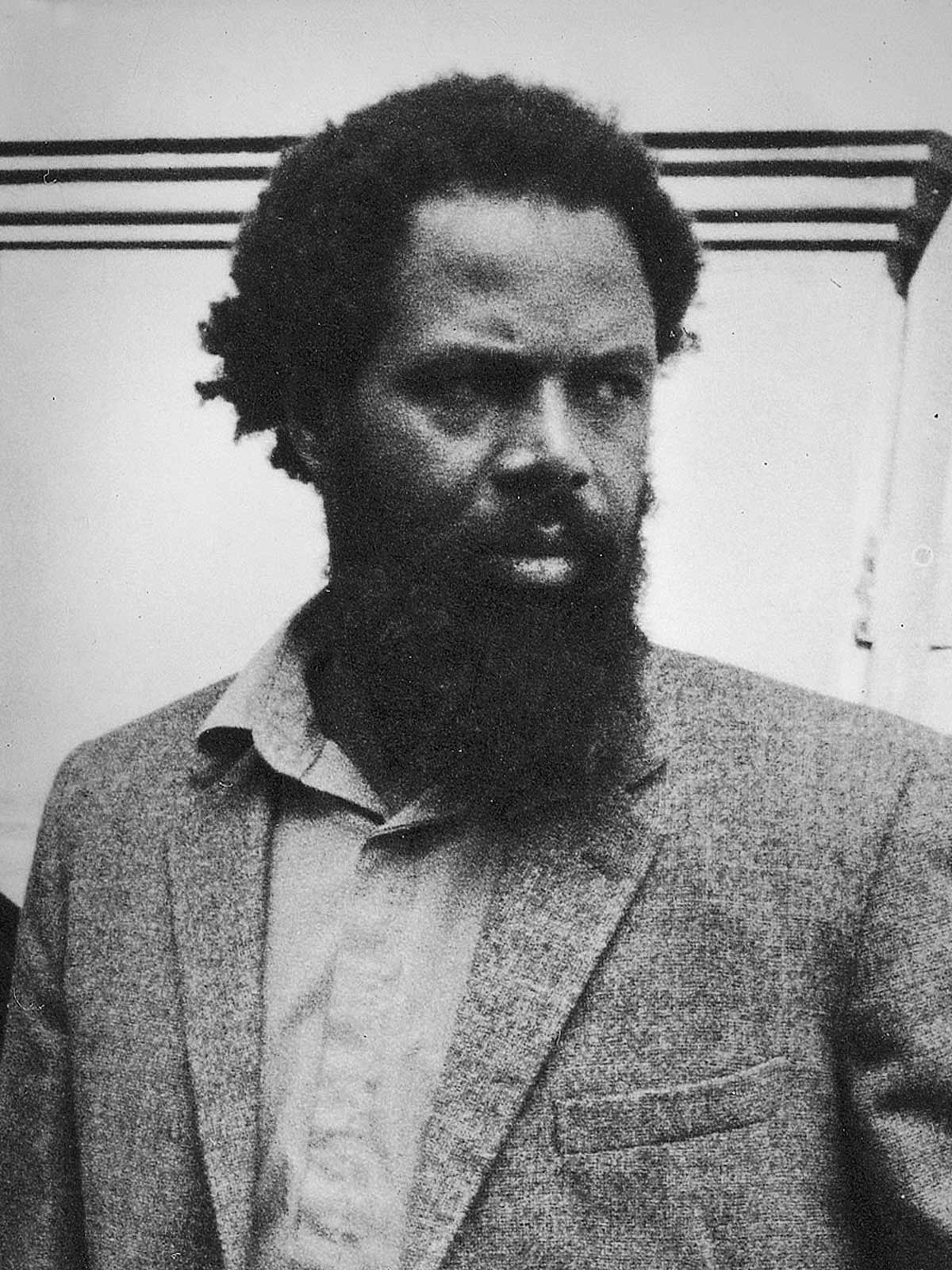

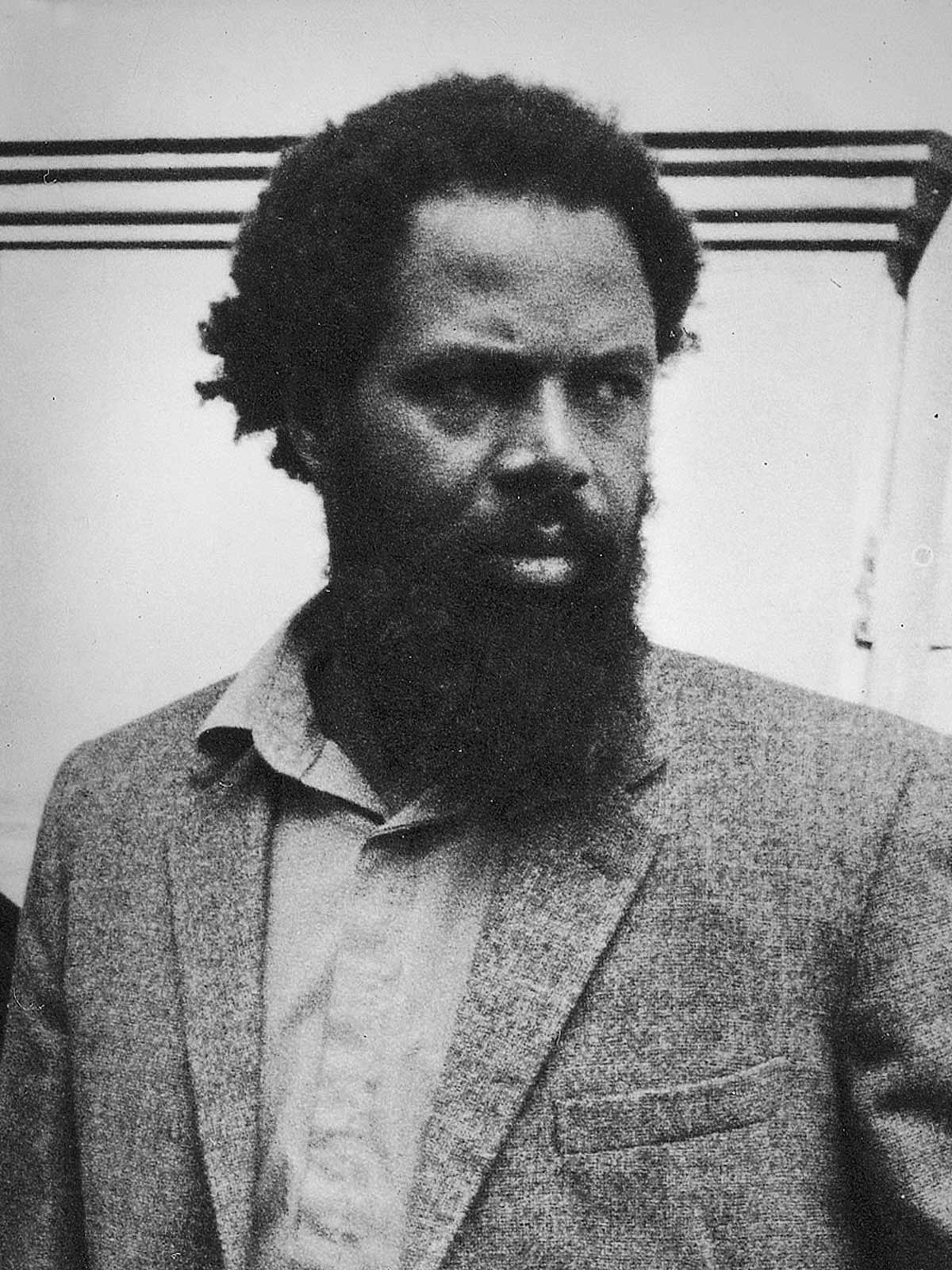

Frank Crichlow in 1970

“Since the decision of the council, police cars have been outside the restaurant almost every night, I assume to check I am complying with the regulations,” he wrote in another letter in early 1970.

“Not once did they ever find evidence of ‘drugs, pimps and prostitutes’ as one policeman said of us who inhabited the Mangrove,” recalls Barbara.

She says the police appeared to resent the restaurant’s popularity - especially with its high profile customers. “To the police, Frank was a Trinidadian businessman gaining too much influence.”

Clive says the police would turn up looking for drugs.

“Everyone knew Frank was anti-drugs - you most certainly couldn’t go there if you had a reputation for being dodgy or selling weed.

“It was harassment. It dragged the restaurant’s reputation down. They saw us black people as a threat.”

In the following months, the police raids persisted. They were “harassing the black community with impunity”, says Barbara.

Frank looked for support from the local Caribbean community and the newly-formed British Black Panthers anti-racist group - which was inspired by the radical political organisation, the Black Panther Party in the US.

A group called “The Action Committee for the Defence of the Mangrove” was created and preparations for a protest march began.

The Mangrove restaurant

“We simply wanted to make visible our opposition to what was happening at the Mangrove,” says Barbara.

The building quickly became a makeshift hub for community activism.

“You had the restaurant upstairs, but downstairs people were busy preparing placards for the march,” says Clive.

Before the protest, the Mangrove committee wrote an open letter to Prime Minister Edward Heath and others.

It said the many “deliberate raids, harassments and provocations” by the police had been reported to the Home Office on many occasions but had fallen on deaf ears.

“This protest is necessary as all other methods have failed to bring about any change in the manner the police have chosen to deal with black people.”

Call to action

One of the reasons given to Frank for his licence removal was that “people with criminal records, prostitutes, and convicted persons” used the Mangrove.

“My restaurant is patronised by respectable people,” wrote Frank on the Race Relations Board complaint form. He also said his premises had been “unlawfully raided” by police on two occasions.

With his new restricted licence, Frank felt he was under close scrutiny.

Frank Crichlow in 1970

“Since the decision of the council, police cars have been outside the restaurant almost every night, I assume to check I am complying with the regulations,” he wrote in another letter in early 1970.

“Not once did they ever find evidence of ‘drugs, pimps and prostitutes’ as one policeman said of us who inhabited the Mangrove,” recalls Barbara.

She says the police appeared to resent the restaurant’s popularity - especially with its high profile customers. “To the police, Frank was a Trinidadian businessman gaining too much influence.”

Clive says the police would turn up looking for drugs.

“Everyone knew Frank was anti-drugs - you most certainly couldn’t go there if you had a reputation for being dodgy or selling weed.

“It was harassment. It dragged the restaurant’s reputation down. They saw us black people as a threat.”

In the following months, the police raids persisted. They were “harassing the black community with impunity”, says Barbara.

Frank looked for support from the local Caribbean community and the newly-formed British Black Panthers anti-racist group - which was inspired by the radical political organisation, the Black Panther Party in the US.

A group called “The Action Committee for the Defence of the Mangrove” was created and preparations for a protest march began.

The Mangrove restaurant

“We simply wanted to make visible our opposition to what was happening at the Mangrove,” says Barbara.

The building quickly became a makeshift hub for community activism.

“You had the restaurant upstairs, but downstairs people were busy preparing placards for the march,” says Clive.

Before the protest, the Mangrove committee wrote an open letter to Prime Minister Edward Heath and others.

It said the many “deliberate raids, harassments and provocations” by the police had been reported to the Home Office on many occasions but had fallen on deaf ears.

“This protest is necessary as all other methods have failed to bring about any change in the manner the police have chosen to deal with black people.”

The march

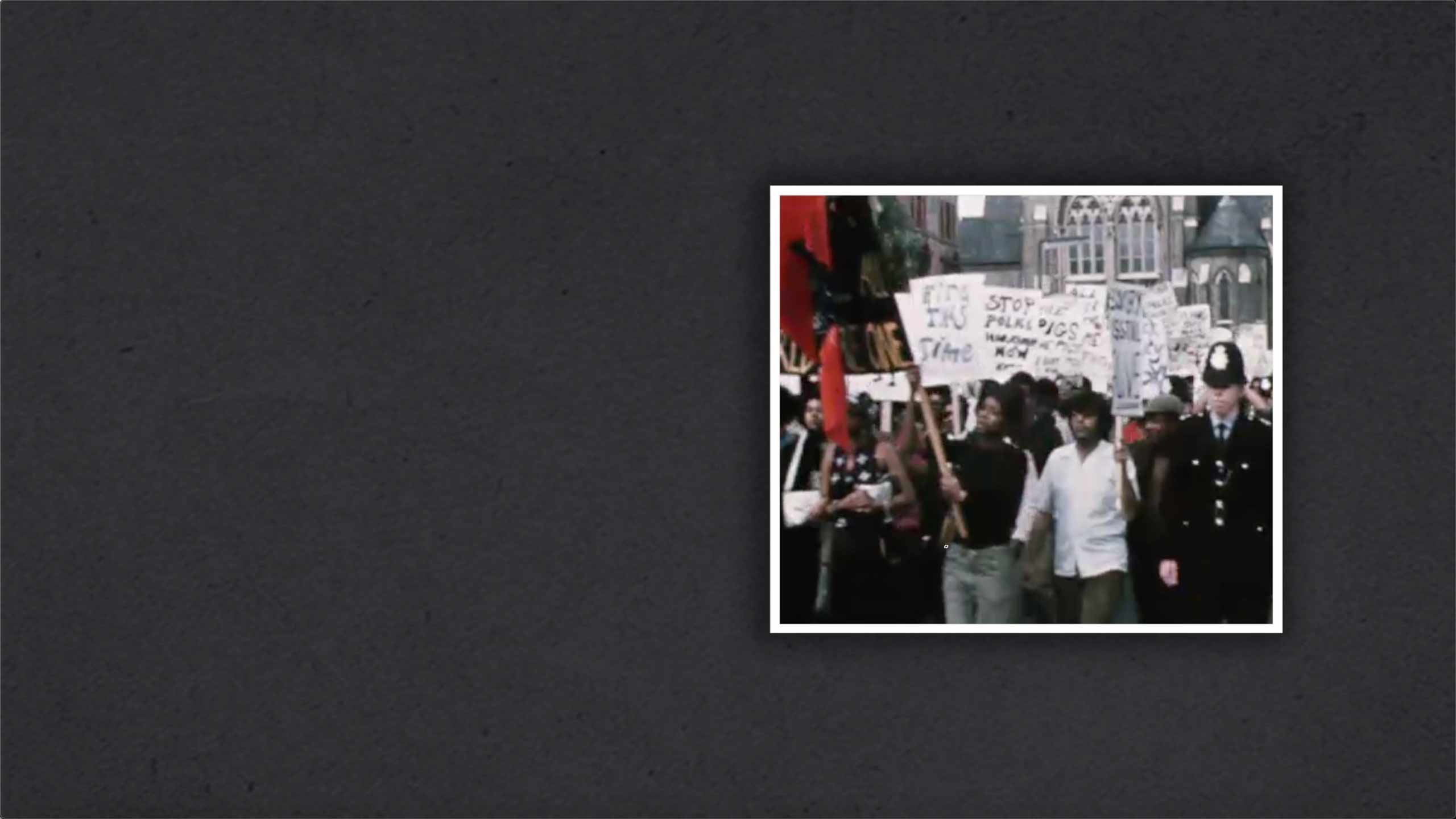

On Sunday 9 August 1970, just after lunchtime, a crowd started to gather in front of the Mangrove.

It was mostly made up of Caribbeans, says Clive - people from Notting Hill, Brixton, Islington and all over London.

About 14:45, according to police notes, there were 100 people there. Photos show demonstrators holding banners painted with phrases like “this is the time”, “black unity now” and “hands off us pigs”. The protesters had at least one pigs head - a derogatory nod at the police - which would be held aloft once they started marching.

The crowd was growing impatient and Clive remembers activist Darcus Howe stood on the roof of a car to address everybody.

“We’ve complained to the police about the police and nothing’s been done,” he said. “We’ve complained to magistrates about magistrates and nothing’s been done. We’ve complained to judges about judges and nothing’s been done. Now it’s time to do something ourselves.”

Remembering her late father, Darcus’s daughter Tamara describes him as being “ferociously committed to fighting injustices”.

“He was always very honest with me about the realities of racism. He was uncompromising on tolerating anything that was remotely racially unjust.”

Tamara Howe

As Darcus spoke, says Clive, about a dozen police officers appeared from around the corner. Darcus pointed at them, and the crowd started shouting “pigs”.

“Enough was enough - we had to stick up for the Mangrove,” says Clive.

The protest had started.

The march

On Sunday 9 August 1970, just after lunchtime, a crowd started to gather in front of the Mangrove.

It was mostly made up of Caribbeans, says Clive - people from Notting Hill, Brixton, Islington and all over London.

About 14:45, according to police notes, there were 100 people there. Photos show demonstrators holding banners painted with phrases like “this is the time”, “black unity now” and “hands off us pigs”. The protesters had at least one pigs head - a derogatory nod at the police - which would be held aloft once they started marching.

The crowd was growing impatient and Clive remembers activist Darcus Howe stood on the roof of a car to address everybody.

“We’ve complained to the police about the police and nothing’s been done,” he said. “We’ve complained to magistrates about magistrates and nothing’s been done. We’ve complained to judges about judges and nothing’s been done. Now it’s time to do something ourselves.”

Remembering her late father, Darcus’s daughter Tamara describes him as being “ferociously committed to fighting injustices”.

“He was always very honest with me about the realities of racism. He was uncompromising on tolerating anything that was remotely racially unjust.”

Tamara Howe

As Darcus spoke, says Clive, about a dozen police officers appeared from around the corner. Darcus pointed at them, and the crowd started shouting “pigs”.

“Enough was enough - we had to stick up for the Mangrove,” says Clive.

The protest had started.

The marchers, numbering as many as 150 by now, intended to walk past several police stations in the area.

They were vastly outnumbered by police.

A police document obtained by historian Paul Field - who co-wrote a biography of Darcus Howe - revealed that 588 constables, 84 sergeants, 29 inspectors and four chief inspectors had been made available to cover the protest.

There was also a handful of plain clothes and Special Branch detectives.

Barbara Beese holding a pig’s head

The number of police officers is something Barbara saw as “ridiculous” - given the march was intended to be “jolly and good spirited”.

Police logs give a minute-by-minute account of the march’s progress. Officers appear to have been unsure of where the protestors were planning to go.

At one stage, an officer spotted a two-tone Volkswagen van in a nearby street and believed it to be “loaded with eggs” which may be “used by demonstrators”.

The marchers, numbering as many as 150 by now, intended to walk past several police stations in the area.

They were vastly outnumbered by police.

A police document obtained by historian Paul Field - who co-wrote a biography of Darcus Howe - revealed that 588 constables, 84 sergeants, 29 inspectors and four chief inspectors had been made available to cover the protest.

There was also a handful of plain clothes and Special Branch detectives.

Barbara Beese holding a pig’s head

The number of police officers is something Barbara saw as “ridiculous” - given the march was intended to be “jolly and good spirited”.

Police logs give a minute-by-minute account of the march’s progress. Officers appear to have been unsure of where the protestors were planning to go.

At one stage, an officer spotted a two-tone Volkswagen van in a nearby street and believed it to be “loaded with eggs” which may be “used by demonstrators”.

The Mangrove march snaked its way west and then north - underneath the now newly open Westway motorway, across the Grand Union Canal and into residential streets north of the main Harrow Road.

“Things turned nasty as we walked down Portnall Road,” says Clive.

Police notes say the procession stopped at about 16.40 and within two minutes there was serious fighting in Portnall Road and neighbouring streets. Officers were calling for assistance and ambulances.

How the fighting started is unclear.

“Some placards had pig heads on them,” says Clive. “That’s how we saw the police given how they treated us black people.”

“I saw a police officer pull down a placard, while a few officers pinned the guy on the ground.

“I could smell trouble.”

Other witnesses gave different accounts.

Police notes say a number of marchers “threw bricks from a builder’s skip and disorder ensued”.

One witness, an elderly woman watching from her window, said that the riot started when a bottle was thrown at a policeman: “The police did not interfere until this occurred.”

A retired postman described a misunderstanding on both sides. Police stopped the procession to let a car cross its path - he said - at which point “as quick as a flash” the march leaders “seemed to lose control”.

The Mangrove march snaked its way west and then north - underneath the now newly open Westway motorway, across the Grand Union Canal and into residential streets north of the main Harrow Road.

“Things turned nasty as we walked down Portnall Road,” says Clive.

Police notes say the procession stopped at about 16.40 and within two minutes there was serious fighting in Portnall Road and neighbouring streets. Officers were calling for assistance and ambulances.

How the fighting started is unclear.

“Some placards had pig heads on them,” says Clive. “That’s how we saw the police given how they treated us black people.”

“I saw a police officer pull down a placard, while a few officers pinned the guy on the ground.

“I could smell trouble.”

Other witnesses gave different accounts.

Police notes say a number of marchers “threw bricks from a builder’s skip and disorder ensued”.

One witness, an elderly woman watching from her window, said that the riot started when a bottle was thrown at a policeman: “The police did not interfere until this occurred.”

A retired postman described a misunderstanding on both sides. Police stopped the procession to let a car cross its path - he said - at which point “as quick as a flash” the march leaders “seemed to lose control”.

At 16:56, police reported that about 50 protestors had started to make their way back to the Mangrove restaurant - but scuffles continued in the streets around Portnall Road for another 20 minutes or so.

By the end, 24 police officers had been injured and 19 arrests had been made.

Nine individuals - including Barbara Beese, Darcus Howe and Frank Crichlow - were charged with incitement to riot and affray.

But these initial riot charges were dismissed by the presiding magistrate through lack of evidence - says Paul Field - and because “police statements were thought to be contradictory”.

One senior officer stated the “melee was spontaneous” and others claimed it was incited by the defendants in order to start a riot. In total, 23 pages of police statements were ruled to be inadmissible by the magistrate.

According to a Sunday Times report from early 1971, a central point to the prosecution’s case was that protesters had allegedly shouted and had banners stating: “Kill the pigs” - a Black Power anti-police slogan imported from America. The words were evidence of violence said prosecutors, but the magistrate disagreed.

Despite this, the director of public prosecutions ended up reinstating the charges.

Special Branch and Home Office documents indicate, says Paul Field, the move was a “deliberate strategy to target and discredit black power leaders”.

The defendants were rearrested.

The Mangrove Nine, as they were becoming known, got ready to defend themselves at the Old Bailey.

A new 大象传媒 drama tells the story of the Mangrove Nine - one of five original films from Bafta and Oscar-winning director Steve McQueen.

Each film in McQueen’s Small Axe anthology tells a different story from London’s West Indian community, where lives have been shaped - despite racism and discrimination - by personal determination.

The trial

Barbara Beese still remembers the atmosphere of the courtroom. “It was male, pale and stale,” she says.

She was about 20 at the time and felt the room was physically very intimidating - with the judge positioned up high.

“The Old Bailey was where the worst criminals went on trial, so for us to be there, it was like being told we were up there with murderers and rapists.”

The strategic way the nine organised their defence is one of the reasons why the trial is considered so significant.

“We took the trial issues head on,” recalls Barbara. “There was very little time to think about the emotional toll of it all. We’d spend all day in the Old Bailey and then meet for hours afterwards to debrief.”

Barbara Beese, Frank Crichlow and Darcus Howe were joined in the dock by Rupert Boyce, Rhodan Gordon, Anthony Innis, Altheia Jones-LeCointe, Rothwell Kentish and Godfrey Millett.

Darcus and Altheia took the bold decision to defend themselves.

Darcus Howe in 2000

It meant they could speak directly to the jury, rather than going through the intermediary of a barrister. The prospect of black people defending themselves in court increased media attention.

The next radical step was the demand, by Darcus, for an all-black jury - or a “jury of peers” - explains Paul Field. The judge was asked to consider an ancient precedent enshrined in the Magna Carta of 1215, which established the principle of the right to justice and a fair trial for all.

“We never saw this as a fair trial and so we hoped an all-black jury would level the playing field,” says Barbara.

She recalls how Altheia, Darcus and the defence barrister Ian MacDonald made legal arguments for two days. “Obviously the judge wasn’t going to have any of that,” she says.

But even then, the defendants used their right to question and dismiss potential jurors. Among other things they were asked what they understood by the term “black power”. Sixty-three were rejected. The final selection included two black people.

Flyer in support of the defendants

In the coming weeks - the Kensington Post newspaper reported at the end of the trial - more than 50 witnesses would be called by the prosecution, and almost twice as many would be called by the defence.

Barbara’s greatest concern was for her - and Darcus’s - baby son.

“Part of the terror was thinking about what would’ve happened to him if we lost the case. I knew the response would have been vindictive in terms of punishment. And, as a black woman brought up in the care system, that’s the last thing I wanted to happen to my son.”

A young teacher, Farrukh Dhondy - a new recruit to the Black Panther movement - was asked to take notes in court.

“A lot of black people came to listen,” he says. “The word about Darcus’s oratory had spread.”

“I would rush off to the Old Bailey after work. I would sit in the gallery every day for an hour or so and take notes.”

Farrukh Dhondy

Darcus and Farrukh were strangers at the time. In the years after, they became close friends.

“Darcus was very theatrical and showed off like hell,” says Farrukh. Remembering Altheia, he says: “Whenever she spoke, you could hear a pin drop.”

The trial ended on Thursday 16 December 1971.

It wasn’t so much the result, as the closing remarks of the judge, that placed the Mangrove Nine in the history books.

All the defendants were acquitted of the main charges of incitement to riot.

Five were acquitted of all charges against them. The remaining four - Rupert Boyce, Rhodan Gordon, Anthony Innis and Altheia Jones-Lecointe - received suspended sentences for a selection of lesser offences, including affray and assaulting police officers.

But it was Judge Edward Clarke’s closing comments that left a lasting mark.

“What this trial has shown is that there is clearly evidence of racial hatred on both sides,” he told the courtroom.

Perhaps it wasn’t so unusual, given the year, for the judge to suggest racism on the part of the defendants. The authorities and press had been accusing the Black Power movement of “anti-white racism” ever since US activist Stokely Carmichael’s visit to the UK in 1967.

But more importantly, it was the first judicial acknowledgment of racism in the Metropolitan Police.

“It was a big moment. Members of the jury even celebrated with us outside the Old Bailey,” says Barbara.

For Farrukh, the ruling “sent a clear message to the British establishment to not go overboard with charging demonstrators.”

The Met Police were not happy.

“All the police officers who gave evidence were at great pains to explain they felt no personal antagonism towards black people within our community,” wrote one senior detective.

“However, when directly questioned, one or two officers stated that they reserved personal views against certain individuals,” he continued.

Senior officers sought, but failed, to get the judge to retract his comments.

The trial

Barbara Beese still remembers the atmosphere of the courtroom. “It was male, pale and stale,” she says.

She was about 20 at the time and felt the room was physically very intimidating - with the judge positioned up high.

“The Old Bailey was where the worst criminals went on trial, so for us to be there, it was like being told we were up there with murderers and rapists.”

The strategic way the nine organised their defence is one of the reasons why the trial is considered so significant.

“We took the trial issues head on,” recalls Barbara. “There was very little time to think about the emotional toll of it all. We’d spend all day in the Old Bailey and then meet for hours afterwards to debrief.”

Barbara Beese, Frank Crichlow and Darcus Howe were joined in the dock by Rupert Boyce, Rhodan Gordon, Anthony Innis, Altheia Jones-LeCointe, Rothwell Kentish and Godfrey Millett.

Darcus and Altheia took the bold decision to defend themselves.

Darcus Howe in 2000

It meant they could speak directly to the jury, rather than going through the intermediary of a barrister. The prospect of black people defending themselves in court increased media attention.

The next radical step was the demand, by Darcus, for an all-black jury - or a “jury of peers” - explains Paul Field. The judge was asked to consider an ancient precedent enshrined in the Magna Carta of 1215, which established the principle of the right to justice and a fair trial for all.

“We never saw this as a fair trial and so we hoped an all-black jury would level the playing field,” says Barbara.

She recalls how Altheia, Darcus and the defence barrister Ian MacDonald made legal arguments for two days. “Obviously the judge wasn’t going to have any of that,” she says.

But even then, the defendants used their right to question and dismiss potential jurors. Among other things they were asked what they understood by the term “black power”. Sixty-three were rejected. The final selection included two black people.

Flyer in support of the defendants

In the coming weeks - the Kensington Post newspaper reported at the end of the trial - more than 50 witnesses would be called by the prosecution, and almost twice as many would be called by the defence.

Barbara’s greatest concern was for her - and Darcus’s - baby son.

“Part of the terror was thinking about what would’ve happened to him if we lost the case. I knew the response would have been vindictive in terms of punishment. And, as a black woman brought up in the care system, that’s the last thing I wanted to happen to my son.”

A young teacher, Farrukh Dhondy - a new recruit to the Black Panther movement - was asked to take notes in court.

“A lot of black people came to listen,” he says. “The word about Darcus’s oratory had spread.”

“I would rush off to the Old Bailey after work. I would sit in the gallery every day for an hour or so and take notes.”

Farrukh Dhondy

Darcus and Farrukh were strangers at the time. In the years after, they became close friends.

“Darcus was very theatrical and showed off like hell,” says Farrukh. Remembering Altheia, he says: “Whenever she spoke, you could hear a pin drop.”

The trial ended on Thursday 16 December 1971.

It wasn’t so much the result, as the closing remarks of the judge, that placed the Mangrove Nine in the history books.

All the defendants were acquitted of the main charges of incitement to riot.

Five were acquitted of all charges against them. The remaining four - Rupert Boyce, Rhodan Gordon, Anthony Innis and Altheia Jones-Lecointe - received suspended sentences for a selection of lesser offences, including affray and assaulting police officers.

But it was Judge Edward Clarke’s closing comments that left a lasting mark.

“What this trial has shown is that there is clearly evidence of racial hatred on both sides,” he told the courtroom.

Perhaps it wasn’t so unusual, given the year, for the judge to suggest racism on the part of the defendants. The authorities and press had been accusing the Black Power movement of “anti-white racism” ever since US activist Stokely Carmichael’s visit to the UK in 1967.

But more importantly, it was the first judicial acknowledgment of racism in the Metropolitan Police.

“It was a big moment. Members of the jury even celebrated with us outside the Old Bailey,” says Barbara.

For Farrukh, the ruling “sent a clear message to the British establishment to not go overboard with charging demonstrators.”

The Met Police were not happy.

“All the police officers who gave evidence were at great pains to explain they felt no personal antagonism towards black people within our community,” wrote one senior detective.

“However, when directly questioned, one or two officers stated that they reserved personal views against certain individuals,” he continued.

Senior officers sought, but failed, to get the judge to retract his comments.

Rothwell’s second trial

After the trial, one of the nine - Rothwell Kentish, faced a separate prosecution.

As a result of his re-arrest in October 1970 - in relation to the Portnall Road violence - he was charged with the attempted murder of a police officer. He was eventually sentenced to 36 months for assault and possession of an offensive weapon.

Rothwell “Roddy” Kentish died in 2019 aged 87.

Joe Kentish with his father Rothwell

“The experience made my dad bitter,” says his 44-year-old son, Joseph. “In his last years, he had dementia and on his deathbed, all he spoke about was the [second] trial.

“He kept asking us to find his court papers. I still feel a massive sense of injustice for him.”

At Roddy’s funeral, a letter was read from the Mangrove Nine barrister, Ian MacDonald, acknowledging that he had borne perhaps the heaviest personal cost of the trial.

Joseph says there’s even a doubt over whether his father was ever at the Mangrove march - with a suggestion he was fixing a car elsewhere.

Joseph Kentish

“As a community leader, police obviously assumed that Dad would’ve had a hand in the march.

“One thing I know is that the period our parents went through was deeply traumatic. They were brilliant and complex people who were deeply affected by those struggles.”

Rothwell’s second trial

After the trial, one of the nine - Rothwell Kentish, faced a separate prosecution.

As a result of his re-arrest in October 1970 - in relation to the Portnall Road violence - he was charged with the attempted murder of a police officer. He was eventually sentenced to 36 months for assault and possession of an offensive weapon.

Rothwell “Roddy” Kentish died in 2019 aged 87.

Joe Kentish with his father Rothwell

“The experience made my dad bitter,” says his 44-year-old son, Joseph. “In his last years, he had dementia and on his deathbed, all he spoke about was the [second] trial.

“He kept asking us to find his court papers. I still feel a massive sense of injustice for him.”

At Roddy’s funeral, a letter was read from the Mangrove Nine barrister, Ian MacDonald, acknowledging that he had borne perhaps the heaviest personal cost of the trial.

Joseph says there’s even a doubt over whether his father was ever at the Mangrove march - with a suggestion he was fixing a car elsewhere.

Joseph Kentish

“As a community leader, police obviously assumed that Dad would’ve had a hand in the march.

“One thing I know is that the period our parents went through was deeply traumatic. They were brilliant and complex people who were deeply affected by those struggles.”

Since the Mangrove...

The message to take from the Mangrove trial is, according to historian Paul Field, that racial discrimination cannot only be “defeated in protests on the streets, but also by black people organising their own defence in the courtroom”.

The Mangrove Nine achieved an incredible feat, he says. They convinced a white-majority jury that the police had “stains of racism” and that the officers’ “trumped up allegations were without foundation”.

But the struggle for racial equality is far from over, says Barbara.

“We thought we were gonna change the world back then. But still, when you look at the disproportionate number of black men in custody and the general climate we find ourselves in, we have to keep on fighting.”

In a statement, a Metropolitan Police spokesperson said: “All of society - of which policing is of course a part - has a role to play in reducing disproportionate outcomes in cases where disproportionality is found to be based on ethnicity alone. We continue to work with Londoners to find a way to police London that saves lives while retaining the confidence of our communities.”

Barbara says black people may be better at defending themselves and calling to account actions of error, but “there are still issues of institutional racism within the police”.

That thought is echoed by Leroy Logan, a black former police superintendent - who worked in the Met for 30 years.

He gave evidence to the inquiry into the 1993 murder of black teenager, Stephen Lawrence - which labelled the force as “institutionally racist”.

Leroy Logan

“We did see improvements for a bit [after the 1999 Lawrence Inquiry], but there are still officers in the force who, for some reason, feel emboldened to have prejudices against black people.”

But for Joseph Kentish - Rothwell’s son - there has been some progress over the years.

“If you’re arrested in London, I do think that as a black man you’re still in serious danger of being hurt and stereotyped - but I don’t think you need to have the same level of fear as my dad.”

The Met says it has come a long way since 1999, and is more scrutinised and accountable than it has ever been, but “appreciates some concerns remain”.

“We do not believe our officers are prejudiced or ignorant - or carry out racist stereotyping,” said a spokesperson. “But that is not to say there are no areas for improvement. Of course there are, as there are in all organisations and institutions today.”

Since the Mangrove...

The message to take from the Mangrove trial is, according to historian Paul Field, that racial discrimination cannot only be “defeated in protests on the streets, but also by black people organising their own defence in the courtroom”.

The Mangrove Nine achieved an incredible feat, he says. They convinced a white-majority jury that the police had “stains of racism” and that the officers’ “trumped up allegations were without foundation”.

But the struggle for racial equality is far from over, says Barbara.

“We thought we were gonna change the world back then. But still, when you look at the disproportionate number of black men in custody and the general climate we find ourselves in, we have to keep on fighting.”

In a statement, a Metropolitan Police spokesperson said: “All of society - of which policing is of course a part - has a role to play in reducing disproportionate outcomes in cases where disproportionality is found to be based on ethnicity alone. We continue to work with Londoners to find a way to police London that saves lives while retaining the confidence of our communities.”

Barbara says black people may be better at defending themselves and calling to account actions of error, but “there are still issues of institutional racism within the police”.

That thought is echoed by Leroy Logan, a black former police superintendent - who worked in the Met for 30 years.

He gave evidence to the inquiry into the 1993 murder of black teenager, Stephen Lawrence - which labelled the force as “institutionally racist”.

Leroy Logan

“We did see improvements for a bit [after the 1999 Lawrence Inquiry], but there are still officers in the force who, for some reason, feel emboldened to have prejudices against black people.”

But for Joseph Kentish - Rothwell’s son - there has been some progress over the years.

“If you’re arrested in London, I do think that as a black man you’re still in serious danger of being hurt and stereotyped - but I don’t think you need to have the same level of fear as my dad.”

The Met says it has come a long way since 1999, and is more scrutinised and accountable than it has ever been, but “appreciates some concerns remain”.

“We do not believe our officers are prejudiced or ignorant - or carry out racist stereotyping,” said a spokesperson. “But that is not to say there are no areas for improvement. Of course there are, as there are in all organisations and institutions today.”

Remembering Frank Crichlow

The Mangrove closed in 1992 and Frank Crichlow died in 2010.

The building where the restaurant was is now private housing. But Barbara says its legacy as a “space for black resistance” lives on.

“People still talk about the Mangrove trial,” says Leroy Logan. “It gave birth to a spirit of activism in the black community.”

Site of the Mangrove restaurant

Darcus Howe’s daughter, Tamara, agrees. She says it produced hope and “tangible guidance on how to self-organise, mobilise and campaign”.

Her father, a writer and broadcaster who campaigned for black rights for more than 50 years, died in 2017.

And what of the recent Black Lives Matter protests - following the death of George Floyd in the US? Are they channelling the spirit of the Mangrove?

“It has been inspiring seeing people come out, telling it like it is,” says Tamara. “I’ve never seen anything like it before. And to be joined by white people? I feel really positive.”

And from one who has spent a lifetime championing black lives - Barbara says she’s now filled with optimism.

Barbara Beese

“The current outcry reflects back to the demands of 1970s black power.

“Every now and then you get these revelatory moments. All I can hope, is that the momentum continues.”

The Mangrove closed in 1992 and Frank Crichlow died in 2010.

The building where the restaurant was is now private housing. But Barbara says its legacy as a “space for black resistance” lives on.

“People still talk about the Mangrove trial,” says Leroy Logan. “It gave birth to a spirit of activism in the black community.”

Site of the Mangrove restaurant

Darcus Howe’s daughter, Tamara, agrees. She says it produced hope and “tangible guidance on how to self-organise, mobilise and campaign”.

Her father, a writer and broadcaster who campaigned for black rights for more than 50 years, died in 2017.

And what of the recent Black Lives Matter protests - following the death of George Floyd in the US? Are they channelling the spirit of the Mangrove?

“It has been inspiring seeing people come out, telling it like it is,” says Tamara. “I’ve never seen anything like it before. And to be joined by white people? I feel really positive.”

And from one who has spent a lifetime championing black lives - Barbara says she’s now filled with optimism.

Barbara Beese

“The current outcry reflects back to the demands of 1970s black power.

“Every now and then you get these revelatory moments. All I can hope, is that the momentum continues.”

Written by Ashley John-Baptiste

Edited by Paul Kerley

Photos by Emma Lynch, Ashley John-Baptiste

Video: 大象传媒 Archives

Other images: Getty Images, National Archives (licensed by the Metropolitan Police), Alamy, Tamara Howe, Joe Kentish

Long Reads editor: Kathryn Westcott

You may also like:

Searching for my slave roots

The NBA wants to talk about race. Is the US ready?