China’s ‘tainted’ cotton

China’s ‘tainted’ cotton

By John Sudworth

China is forcing hundreds of thousands of Uighurs and other minorities into hard, manual labour in the vast cotton fields of its western region of Xinjiang, according to new research seen by the ´óÏó´«Ã½.

Based on newly discovered online documents, it provides the first clear picture of the potential scale of forced labour in the picking of a crop that accounts for a fifth of the world’s cotton supply and is used widely throughout the global fashion industry.

Alongside a large network of detention camps, in which more than a million are thought to have been detained, allegations that minority groups are being coerced into working in textile factories have already been well documented.

The Chinese government denies the claims, insisting that the camps are “vocational training schools” and the factories are part of a massive, and voluntary, “poverty alleviation” scheme.

But the new evidence suggests that upwards of half a million minority workers a year are also being marshalled into seasonal cotton picking under conditions that again appear to raise a high risk of coercion.

“In my view the implications are truly on a historical scale,” Dr Adrian Zenz, a senior fellow at the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation in Washington , told the ´óÏó´«Ã½.

“For the first time we not only have evidence of Uighur forced labour in manufacturing, in garment making, it’s directly about the picking of cotton, and I think that is such a game-changer.

“Anyone who cares about ethical sourcing has to look at Xinjiang, which is 85% of China’s cotton and 20% of the world’s cotton, and say, ‘We can’t do this anymore.’”

"For the regions of Hotan and Aksu alone, the number of cotton pickers moved to the military corps reached 150,000 and 60,000 each"

The documents, a mixture of online government policy papers and state news reports, show that in 2018 the prefectures of Aksu and Hotan sent 210,000 workers “via labour transfer” to pick cotton for a Chinese paramilitary organisation, the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps.

"Adopt methods to mobilise and organise"

Others speak of pickers being “mobilised and organised” and transported to fields hundreds of kilometres away.

"142,700... transferring all those who should be transferred.”

This year, Aksu identified a need for 142,700 workers for its own fields, which was largely met through the principle of “transferring all those who should be transferred.”

References to “guiding” the pickers to “consciously resist illegal religious activities” indicate that the policies are designed predominantly for Xinjiang’s Uighurs and other traditionally Muslim groups.

Government officials first sign “contracts of intent” with the cotton farms, determining the “number of workers hired, the location, the accommodation and wages,” after which pickers are then mobilised to “enthusiastically sign up”.

There are plenty of clues that this enthusiasm is less than whole-hearted. One report describes a village where people were “unwilling to work in agriculture”.

Officials had to visit again to perform “thought education work”. Eventually 20 were sent off, with a plan in place to “export” 60 more.

Camps and Factories

China has long used the mass relocation of its rural poor - with the stated aim of improving their employment prospects - as part of a national anti-poverty campaign.

In recent years, those efforts have gone into overdrive.

Arguably President Xi Jinping’s most important domestic political priority, the goal is to eliminate absolute poverty in time for the Communist Party’s centenary next year.

But in Xinjiang there is evidence of a far more political purpose and much higher levels of control, as well as massive which officials are under pressure to meet.

A marked shift in China’s approach to the region can be traced back to two brutal attacks on pedestrians and commuters in Beijing in 2013 and the city of Kunming in 2014, blamed by China on Uighur Islamists and separatists.

Its response, from 2016 onwards, has been the building of “re-education” camps for anyone displaying any behaviour viewed as a potential sign of untrustworthiness, such as installing an encrypted messaging app on a phone, viewing religious content or having a relative living overseas.

While China calls them “schools for de-radicalisation”, suggest that the reality is a draconian system of internment which aims to replace old identities of faith and culture with an enforced loyalty to the Communist Party.

But the construction work didn’t stop with the camps.

Since 2018, a huge industrial expansion has been under way involving the building of hundreds of factories.

The parallel purpose of mass employment and mass internment is made clear by the appearance of many factories within the walls of the camps, or in close proximity to them.

Work, the government appears to believe, will help transform the of Xinjiang’s minorities and remake them as modern, secular, wage-earning Chinese citizens.

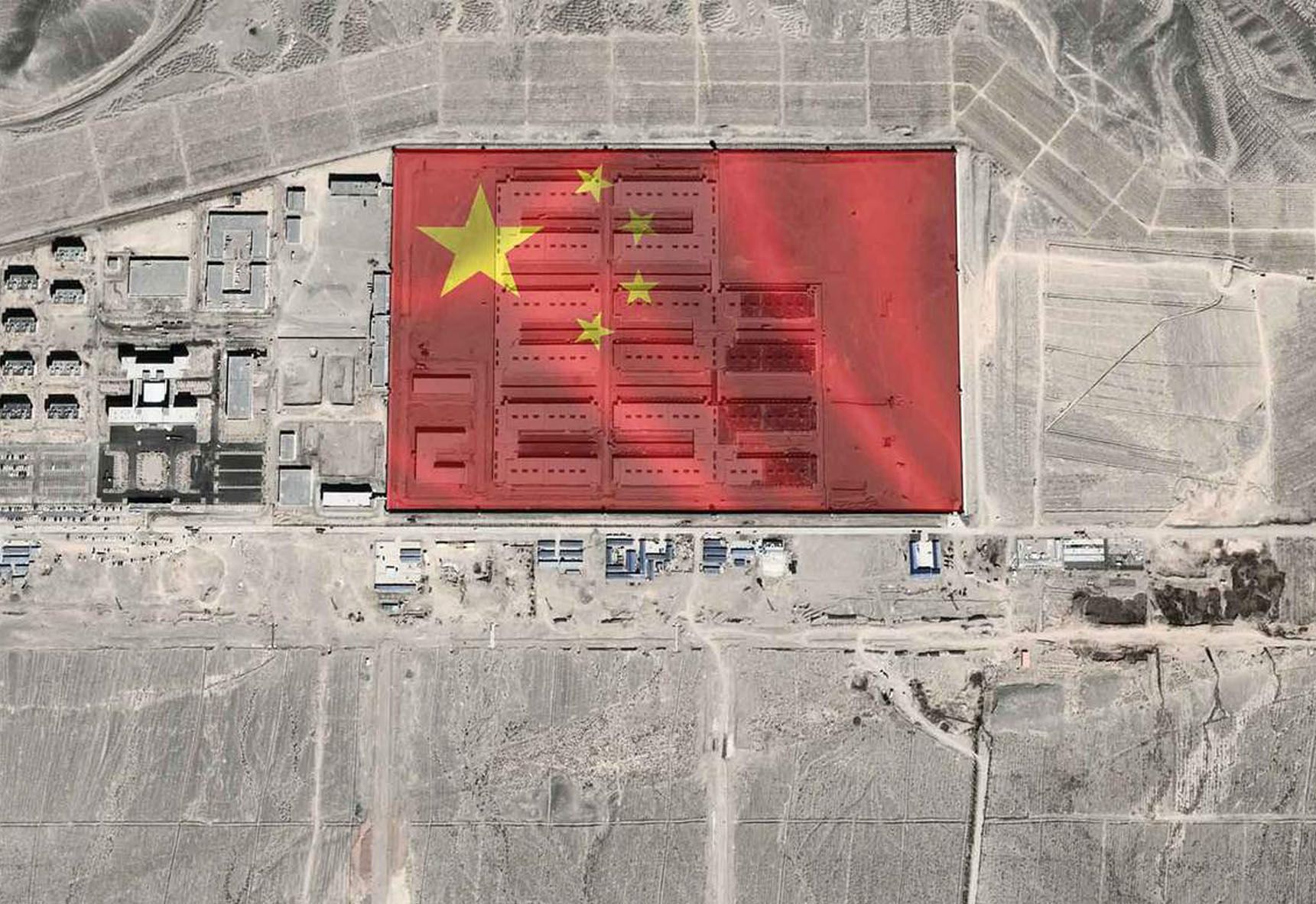

This facility built in 2017 in the city of Kuqa, has been identified as a re-education camp by researchers

Open-source satellite images show internal security walls and what appears to be a guard tower.

A new factory appeared next door in 2018. Shortly after construction finished, the satellite picked up something significant.

Independent analysts confirm that masses of people, all apparently wearing the same colour uniforms, can be seen walking in close formation between the two sites.

When the ´óÏó´«Ã½ tried to visit, a number of unmarked cars followed us as we filmed the perimeter of the complex.

The factory and the camp now appear to have been amalgamated into one large factory complex, plastered with propaganda slogans extolling the benefits of the anti-poverty campaign.

Before long we were stopped from filming and forced to leave.

According to local state-run media, the textile factory employs up to 3000 people “under the mobilisation and organisation of the government”.

But it’s impossible to verify who the people in the satellite image are or what the conditions for the workers in the facility are like today.

Questions sent directly to the factory have gone unanswered.

The ´óÏó´«Ã½ was repeatedly stopped, questioned, prevented from filming and tailed by multiple unmarked cars for hundreds of kilometres across Xinjiang

The ´óÏó´«Ã½ was repeatedly stopped, questioned, prevented from filming and tailed by multiple unmarked cars for hundreds of kilometres across Xinjiang

Deep rooted lazy thinking

Despite the link between camps and factories, it is mostly those who haven’t been detained who are the of Xinjiang’s poverty alleviation campaign.

Often from poor farming or herding families, more than two million of them have been mobilised for work, in many cases after first being put through short bouts of “military-style” job training.

So far, the available evidence suggests that, like the camp inmates, they too have been used as a source of labour in factories and, in particular, Xinjiang’s booming textile mills.

In July this year, the US based Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) that it was “possible” that minorities were also being sent to pick cotton, but “more information is needed.”

The new documents found by Dr Zenz not only provide that information, they also reveal a clear political purpose behind this mass transfer of minorities into the fields.

An August 2016 notice issued by the Xinjiang regional government on the management of cotton pickers instructs officials to “strengthen their ideological education and ethnic unity education”.

One propaganda report found by Dr Zenz suggests that the cotton fields present an opportunity to transform the “deep-rooted, lazy thinking” of poor, rural villagers by showing them that “labour is glorious”.

Such phrases echo the Chinese state’s view of Uighur as acting as a barrier to modernisation.

A desire to stay home and “bring up children” is described as an “important cause of poverty” by another propaganda report about the benefits of cotton picking.

The state is providing “centralised” systems of care for children, the elderly and for livestock, so that everyone is “freed from the worries of going out to work.”

And there are many references to how the mobilised cotton pickers are subject to controls and surveillance seemingly at odds with any normal employment practice.

A policy document from Aksu, dated October this year, decrees that cotton pickers must be transported in groups and accompanied by officials who “eat, live, study and work with them, actively implementing thought education during cotton picking”.

Mahmut, not his real name, is a young Uighur now living in Europe who cannot return to Xinjiang because a history of overseas travel is one of the main reasons for internment in a camp.

Contact with his family back home is also now far too risky for them. But when they last spoke in 2018 he heard that both his mother and sister had been transferred to work.

“They took my sister to Aksu City, to a textile factory,” he tells me. “She stayed in that factory for three months and didn’t get any money.

“In winter, my mother was picking cotton for government officials - they say they need five or ten per cent of the village, they come to every family door by door.

“People go because they’re afraid of being taken to jail or somewhere else.”

Over the past five years, these door-to-door visits have become a key mechanism of control in Xinjiang, with 350,000 officials despatched to gather detailed, intrusive information on every single minority household.

Those being called to work by these “village-based work teams” will be only too aware that they are also instrumental in deciding who should be sent to a camp.

“Completely fabricated”

Xinjiang’s cotton growing industry used to rely on seasonal, migrant workers from other provinces in China.

But cotton picking is notoriously hard work and rising wages and better jobs elsewhere mean the migrants have stopped coming.

Now propaganda reports write glowingly of how the newly found supply of local labour has both solved this labour crisis and helped increase profits for the growers.

But nowhere is there any real explanation of why hundreds of thousands of people, who apparently had no previous interest in picking cotton, should suddenly rush into the fields.

Although the documents claim that pay levels can top 5000 RMB ($763, £570) a month, one report appears to suggest that for 132 pickers organised from one village, the average monthly salary was just 1,670 RMB ($255, £188)) each.

Whatever the salary level, paid labour can still be considered forced labour under the relevant .

In response to questions submitted to China’s foreign ministry, the ´óÏó´«Ã½ received a faxed statement saying: “Workers from all ethnic groups in Xinjiang choose their jobs according to their own free will and sign voluntary employment contracts in accordance with the law.”

Xinjiang’s poverty rate has fallen from almost 20% in 2014 to a little more than 1% today, it said.

And it dismissed accusations of forced labour as “completely fabricated”, saying instead that China’s critics wanted to cause “forced unemployment and forced poverty” in Xinjiang.

“The smiling faces of all of Xinjiang’s ethnic groups are the most powerful response to America’s lies and rumours,” it added.

But the Better Cotton Initiative, an independent industry body that promotes ethical and sustainable standards, told the ´óÏó´«Ã½ that concerns over China’s poverty alleviation scheme were one of the main reasons they’ve recently decided to stop auditing and certifying farms in Xinjiang.

Director of standards and assurance, Damien Sanfilippo, said: “We’ve identified the risk that poor, rural communities would be coerced into employment linked to this poverty alleviation programme.

“Even if these workers get a decent wage – which is possible – they may not have chosen that employment freely.”

Mr Sanfilippo, who also cited the increasingly restricted access to Xinjiang for his international monitors as another factor, said the organisation’s decision to walk away only further raises the risk for the global fashion industry.

“To the best of my knowledge there isn’t any organisation that is active locally who can provide verification for that cotton.”

The ´óÏó´«Ã½ approached 30 major international brands. Three – Marks and Spencer, Next, and Tesco – told us they have policies in place that ensure products sourced from China do not use raw cotton from Xinjiang. Burberry said they do not use any cotton from China at all. Others, including those who don't source direct from Xinjiang, were unable to guarantee its cotton didn't enter supply chains elsewhere. Nine companies gave no response.

As we prepare to leave Xinjiang, just outside the city of Korla we pass a location that was, as recently as 2015, a patch of open desert.

It is now home to a giant, prison camp complex, with what independent analysts say are multiple factory buildings visible inside.

We believe this is the first independent footage of the colossal site.

It is just one of many such complexes that now dot the landscape, and a chilling final reminder of the blurred boundaries between mass incarceration and mass labour in Xinjiang.

Credits

Author: John Sudworth

Field Producer/Camera: Kathy Long

Camera: Wang Xiqing

Editor: Kathryn Westcott

Graphics: Debie Loizou, PlanetLabs

Online Producer: James Percy

Published: December 2020