Autism brain secrets revealed by scan

- Published

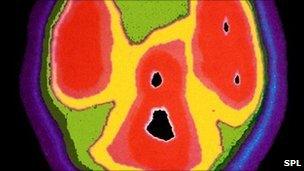

Brain scans are shedding light on autism

Differences in the brain structure of people carrying an "autism gene" may offer clues to how the condition develops, say US scientists.

Scans revealed children carrying the gene variant appeared to have more nerve cell "connections" within the frontal lobe.

They had fewer connections between this and the rest of the brain, reported Science Translational Medicine journal.

Brain research has just begun to reveal autism's roots, a UK expert said.

One-third of the population carry the CNTNAP2 gene variant, so it does not guarantee that autism will develop, but just slightly increases the risk.

Different pathways

However, scientists at the University of California in Los Angeles believe it may influence the way the brain is "wired".

They used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to look for communication between different brain regions, and to measure the strength of these connections.

They scanned the brains of 32 children as they performed learning-related tasks - half had autism, and half did not.

Regardless of their diagnosis, those carrying the CNTNAP2 variant had differences in the connections within the frontal lobe of the brain itself and between the frontal lobe and the rest of the brain.

Dr Ashley Scott-Van Zeeland, who led the research, said: "The front of the brain appears to talk mostly to itself - it doesn't communicate as much with other parts of the brain and lacks long-range connections to the back of the brain."

The researchers also spotted differences in the "wiring" between the frontal lobe and the left and right sides of the brain.

In children with the version of the gene not linked to autism risk, the pathways were linked more strongly to the left side of the brain.

In those with the "risk variant", the pathways were different, linking the lobe strongly to both sides of the brain.

This, said the researchers, could explain why the gene variant had been linked to children who are slow in starting to talk.

Dr Scott-Van Zeeland said that if the gene variant did predict language problems, then it might be possible to design therapies which helped to "rebalance" the brain and encourage normal development.

Professor Margaret Esiri, a neuroscientist from Oxford University, said that researchers had so far "barely scratched the surface" of understanding the interplay between genes and brain development.

Her own research closely analyses a scarce supply of donated brains from both autistic and non-autistic adults and children to look for differences in structure and function.

She said: "If you understand these subtle differences, there may be ways of 'tweaking' them earlier in life, and bringing them back into a normal trajectory of development. Of course, this would be many years away."

Carol Povey, from the National Autistic Society, said the study was interesting because it began to link genes thought to be involved in autism to actual changes in brain function.

She said: "The causes of autism are as yet unknown, but we do know there are likely to be many factors involved, so we hope this will contribute to our understanding of this complex condition."

- Published10 August 2010

- Published11 August 2010