Scientists make 'laboratory-grown' kidney

- Published

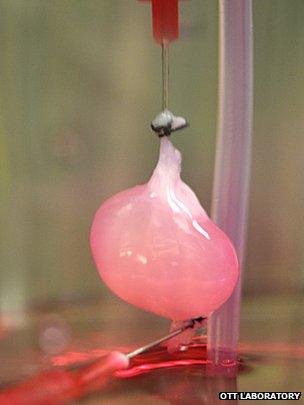

The rat kidney was grown in the laboratory

A kidney "grown" in the laboratory has been transplanted into animals where it started to produce urine, US scientists say.

Similar techniques to make simple body parts have already been used in patients, but the kidney is one of the most complicated organs made so far.

A study, , showed the engineered kidneys were less effective than natural ones.

But regenerative medicine researchers said the field had huge promise.

Kidneys filter the blood to remove waste and excess water. They are also the most in-demand organ for transplant, with long waiting lists.

The researchers' vision is to take an old kidney and strip it of all its old cells to leave a honeycomb-like scaffold. The kidney would then be rebuilt with cells taken from the patient.

This would have two major advantages over current organ transplants.

The tissue would match the patient, so they would not need a lifetime of drugs to suppress the immune system to prevent rejection.

It would also vastly increase the number of organs available for transplant. Most organs which are offered are rejected, but they could be used as templates for new ones.

Scaffolding

Researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital have taken the first steps towards creating usable engineered kidneys.

They took a rat kidney and used a detergent to wash away the old cells.

The remaining web of proteins, or scaffold, looks just like a kidney, including an intricate network of blood vessels and drainage pipes.

This protein plumbing was used to pump the right cells to the right part of the kidney, where they joined with the scaffold to rebuild the organ.

It was kept in a special oven to mimic the conditions in a rat's body for the next 12 days.

When the kidneys were tested in the laboratory, urine production reached 23% of natural ones.

The team then tried transplanting an organ into a rat. Once inside the body, the kidney's effectiveness fell to 5%.

Yet the lead researcher, Dr Harald Ott, told the “óĻó“«Ć½ that restoring a small fraction of normal function could be enough: "If you're on haemodialysis then kidney function of 10% to 15% would already make you independent of haemodialysis. It's not that we have to go all the way."

He said the potential was huge: "If you think about the United States alone, there's 100,000 patients currently waiting for kidney transplants and there's only around 18,000 transplants done a year.

"I think the potential clinical impact of a successful treatment would be enormous."

'Really impressive'

There is a huge amount of further research that would be needed before this is even considered in people.

The technique needs to be more efficient so a greater level of kidney function is restored. Researchers also need to prove that the kidney will continue to function for a long time.

There will also be challenges with the sheer size of a human kidney. It is harder to get the cells in the right place in a larger organ.

Prof Martin Birchall, a surgeon at University College London, has been involved in windpipe transplants produced from scaffolds.

He said: "It's extremely interesting. It is really impressive.

"They've addressed some of the main technical barriers to making it possible to use regenerative medicine to address a really important medical need."

He said that being able to do this for people needing an organ transplant could revolutionise medicine: "It's almost the nirvana of regenerative medicine, certainly from a surgical point of view, that you could meet the biggest need for transplant organs in the world - the kidney."

- Published21 March 2012