We've updated our Privacy and Cookies Policy

We've made some important changes to our Privacy and Cookies Policy and we want you to know what this means for you and your data.

Imaging 'promises pinpoint cancer treatment'

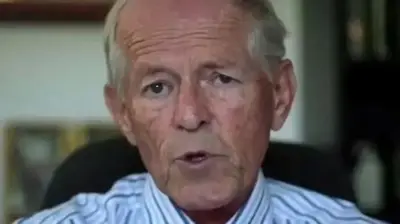

- Author, Dr David Breen

- Role, Southampton General Hospital

New cancer drugs often grab the headlines. But radiological imaging and its increasingly central role in cancer detection and now cancer surgery does not.

In this week's Scrubbing Up, David Breen, an interventional radiologist at the University Hospital of Southampton says this is a major oversight - because it can enable earlier diagnosis and "truly minimally invasive" cancer treatment.

Developments in radiology - medical imaging - are widely acknowledged within the medical community as one of the most significant advances in cancer care in the last few decades.

Imaging, by means of CT, MRI or PET scanning is now enabling both the detection and characterisation of tumours at a smaller size, and increasingly those of less than one centimetre in the liver, lungs and kidneys.

Cancer care has for some time been based on the major tenets of surgical oncology - 'cutting it out', medical oncology - 'poisoning it' and radiation oncology - 'irradiating it', but the diagnosis of smaller cancers by radiologic imaging - frequently through "at-risk investigation" or incidentally in the asymptomatic 'scanned' patient - suggests other possibilities.

Can small tumours be treated in situ, and to similar patient benefit, without involving the costs and complications of traditional surgery?

Amidst the publicity achieved by the big pharmaceutical companies for targeted and patient-specific drugs it is striking how little attention has been paid to developments in minimally-invasive, "interventional oncology".

This arena has been developed from within interventional radiology and might be best described as moving from open, and even "keyhole" (laparoscopic) surgery, towards "pinhole", or image-guided surgery.

Hot and cold

Today cancers are diagnosed by radiological imaging and from a treatment viewpoint this is perhaps also the best way to deliver less invasive therapies.

This is with the aim of avoiding opening the patient's body (at least for small tumours) or exposing the entire patient to systemic (whole body) chemotherapy where this is not necessary.

Developments within interventional oncology are well illustrated by the rapid evolution, in the last 20 years, of tissue ablative technologies - which destroy cancerous tumours in situ - such as radiofrequency ablation (using heat to destroy cancer cells), microwave ablation (which uses electromagnetic waves) or cryoablation (freezing tissue).

A number of publications are testifying to the increasing efficacy of this approach for small volume liver, lung and kidney cancers.

We have just published research on image-guided cryoablation of small renal (kidney) cancers.

Only one of 147 patients had a recurrence of their cancer in an average follow-up of 20 months.

This suggests an outcome potentially as good as that seen with more traditional surgical resection.

Importantly - in the current environment - this was achieved with considerably lower costs, shorter bed stay and fewer complications.

'Clear trend'

Vascular catheters - also developed within interventional radiology - can be used to reach tumours via the arteries that supply them.

They are then in a position to deliver targeted drug therapies to liver tumours by means of drug-releasing particles, a process known as chemo-embolisation.

Similarly particles which deliver short-range irradiation to tumours are being injected via catheters under imaging control to treat liver tumours - 'radio-embolisation'.

Embolisation in these settings, aims to deliver far higher concentrations of drugs and radiation to the tumour site than could be tolerated via the traditional, whole body approach.

These techniques are fundamentally driven by radiological imaging and the clear trend towards the detection of smaller cancers.

It is striking then that the growing subspecialty of 'interventional oncology' has attracted so little public attention and, perhaps as a result, barely features in the national cancer research portfolio, so dominated by drug trials, largely funded by the large pharmaceutical companies.

Time then for some public demand and public-private investment in this promising new arena of cancer care, as is already occurring in other more responsive health care economies around the world.

There is now a need for research into and commitment to image-guided ablation, rather than open surgery, for smaller liver, lung and kidney cancers.

Top Stories

More to explore

Most read

Content is not available