Should we expect more on cancer?

- Published

- comments

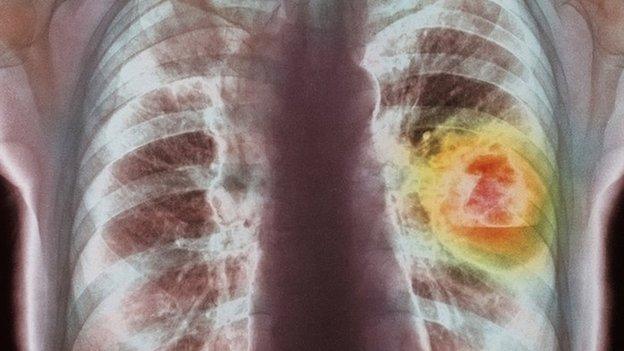

The UK performs poorly on lung cancer survival compared with other developed countries

It seems like a churlish question to be asking after such a remarkable improvement.

But despite a doubling in 10-year cancer survival rates since the early 1970s, there is a nagging sense that the picture set out by Cancer Research UK could be even better.

Granted, the last 40 years have been a story of almost continuous improvement - so much so that cancer, in many cases, has effectively gone from being a death sentence to a chronic condition.

And yet it is understandable that we should want more.

International comparisons still show the NHS lagging behind other western nations. The study published in the Lancet in December last year revealed the UK was doing significant worse in terms of colon, ovary, kidney, stomach and lung cancers in particular.

It is a point picked up by Prof Michel Coleman, who crunched the figures for Cancer Research UK.

He highlights the fact the UK has a particularly poor record when it comes to early diagnosis. This is essential, as the earlier the disease is found the easier it is to treat.

What is the cause of this? Well, there is clearly an issue with improving public awareness about the symptoms. This can be seen from the success of the 2012 government campaign urging people with persistent coughs to go to their GPs, which saw lung cancer diagnosis rates jump by nearly 10%.

But there is also a problem with GPs recognising cancer. A quarter of cancers are still diagnosed after an visit to A&E.

A 2012 lung cancer campaign about persistent coughs boosted diagnosis

To be fair, the average GP will only see six to eight new cancers each year and for the most rare types, such as brain cancer, it is a once-a-decade situation.

Prof Coleman says, therefore, it would "not be right to blame GPs", but he acknowledges it raises questions about the way cancer diagnosis is handled by the health service.

In the NHS, GPs act as gatekeepers to the system in a way that doesn't happen in many other countries.

This is one of the reasons the NHS is considered one of the most efficient in the world, but in terms of speedy cancer diagnosis it could be a barrier.

However, research has also shows that it is not all down to early diagnosis. Even in areas where the NHS does well in terms of detection (breast and colon cancers to name two) survival rates are still not up there with the best.

This suggests there is an issue with getting access to effective treatment. While much of the focus is often on drugs, surgery is by far a more important factor when it comes to cancer treatment.

There is nothing to suggest UK-trained doctors are any worse than those from other countries (in fact there is plenty showing they are among the best).

But the NHS has been found to be lacking when it comes to vital equipment, such as MRI scanners. This can mean there are problems with identifying how far the cancer has spread and, as a result, how effective the treatment can be.

Cancer Research UK wants to see 10-year survival rates continue increasing. If this is to happen, tackling these issues will be just as important as investing in research to develop new technologies and treatments.