Cancer drugs row: A sign of things to come?

- Published

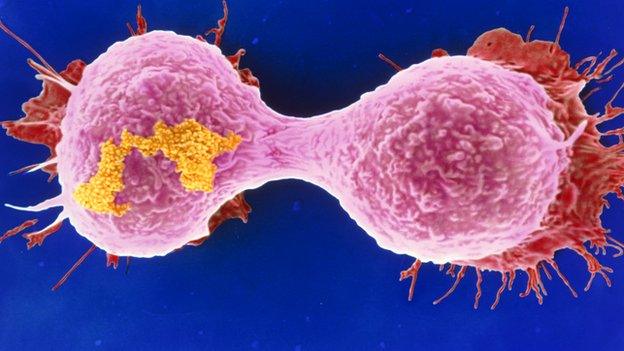

Breast cancer cells dividing

There is a real sense of sadness - and anger for that matter - that the new breast cancer drug Kadcyla looks unlikely to be made routinely available on the NHS, something that is obvious from the bitter language being used by both sides.

The decision by England's official NHS advisory body, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), to reject Kadcyla prompted manufacturers Roche to claim the system was "broken".

NICE - not known for its strong use of language - responded by saying it was "really disappointed" in the approach taken by the drugs firm.

At the heart of this dispute is price. While the drugs are not a cure, they are effective at giving women with an aggressive form of the disease an average of six months of extra life expectancy.

But the drugs do not come cheap. A course of treatment costs Ā£90,000 - more than five times what NICE would normally sanction.

When the row erupted in April after the watchdog first took a look at the drug, the two sides agreed to keep talking.

Cost-effectiveness

The drug Kadcyla costs around Ā£90,000 for an average course of treatment

Several discussions were held during which NICE took the fairly unusual step for a breast cancer treatment of agreeing to consider Kadcyla as an end-of-life therapy.

This meant NICE could sanction spending twice what it was originally proposing to do. But this still wasn't enough.

Officials at Roche told me that they were willing to come down on price "significantly", but that there was a limit to this considering other European countries, including Sweden, Switzerland, Denmark and Austria had agreed to pay the full price.

Comparisons between health systems are hard as the NHS is pretty unique in terms of how it is funded - and in terms of cost-effectiveness it is often lauded as among the best in the world.

But the case of Kadcyla does raise some interesting questions for cancer treatment.

In recent years NICE has become less likely to approve cancer drugs. Since 2012, there have been 14 treatments given the green light and 22 blocked - a rejection rate of 61%.

That compares to 48 rejections out of 148 appraisals since NICE started doing looking at drugs for the NHS in 2000 - a rejection rate of 32%.

There are two schools of thought about why this is.

One is that as medicine has developed - particularly for this disease which has attracted a lot of funding over the years - it has become more and more difficult to produce new drugs that represent a significant improvement on what is already available.

The other - and as you would expect it is one being put strongly by the drugs industry - is that the way NICE assesses drugs is out-of-kilter with modern medicine.

It is a debate that looks set to run and run.