We've updated our Privacy and Cookies Policy

We've made some important changes to our Privacy and Cookies Policy and we want you to know what this means for you and your data.

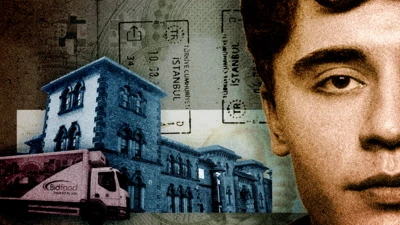

It took me 20 years to talk about my childhood

Image source, Claudio Yanez

Claudio Yanez always preferred not to talk about his childhood. He kept his distance from people and threw himself into his education and career. But a government report published last year about abuses in the public child care system in Chile brought back terrible memories of being taken into care at the age of 10. This is his story.

My mother was 23 years old when I was born. We lived in the centre of Chile. She was a cleaning lady and she wasn't permitted to take me to work so she'd leave me with my godmother, who also worked as a cleaner.

When I was six years old I went to live with my grandmother in a remote town in the north and from then on I was sort of handed over from one place to the next - sent back to live with my father, then with my mother, then with my godmother.

It was impossible for me to bond with anyone - whenever I tried to establish a relationship with someone I was sent somewhere else.

Top Stories

I was emotionally confused. The person whom I thought was my mother wasn't my mother at all - she was my godmother.

I didn't feel that I was loved by anyone and as a child you feel those things - that no-one wants you, that you're a bother, and that's why they kept moving me around.

Top Stories

Find out more

I had very erratic behaviour, I became very frustrated and violent to a point where they didn't want me to be there and I didn't want to be there either.

I rebelled against my mother and against her husband. I didn't like the conditions that they were living in - it was place that had no drinking water, no electricity.

The only place I really liked was school, it was like an escape for me. I went there not only to learn but to be with friends, to be entertained, anything but to be at home where I didn't want to go. I wished that the school hours were longer.

I ran away a lot from home. I would go out and sleep anywhere, on the hillвҖҰ I just didn't want to go back to a place where I wasn't wanted.

All of sudden an adult showed up and took me to what in Chile we call a public care centre. But those places aren't really care centres, they're more like jails. They're very violent places, they're very aggressive places. There was extreme mistreatment there, not just from the workers, but also from the children themselves.

Image source, Claudio Yanez

Top Stories

There was sexual abuse, there was corporal punishment, I'd never imagined I could be hit so hard. There was no access to education, no access to health services. There was this military language that they used with us. It was just a very dire situation.

There was a lot of abuse of power, like the time when they just pulled out the biggest boy and gave him a ladle and told him to strike us as hard as he could. All of us were crying from the blows that he gave us, and the person in charge was just laughing. He thought it was a big, big joke. He saw that we were crying so he reprimanded the big boy for having hit us so hard. He hit this big boy, so he ended up crying as well. But they were all laughing.

I realised that I was alone, that I could only depend on myself, and that it was up to me what I was going to become. I could become a crook, I could become a drug addict, but I could also become a good person.

But it was a very, very painful and difficult thing to realise that I was on my own, that there wasn't anyone else there for me.

I was lucky enough to be recommended for a psychological test. The results came back and it so happened that I had a high IQ, so I became the first child from that place who was allowed to go to school. When the other students would go back to their houses after school I would go back to this place which for me was a jail.

I had a social worker that I could talk to and complain to, and they knew what was happening but they wouldn't listen. And if complaints ever got back to the people who were doing the abuse it would be worse for us, so our choice was to bear it and keep quiet.

There was no camaraderie because this system mutilates your emotions - you feel nothing. You don't feel any empathy, you don't feel any sympathy. That happened to me, the moment I went in there was a change in my DNA.

I got to the point where I didn't feel anything.

I was seeing this boy who was about to be raped and I felt nothing, because you're there, in the law of the jungle, and you have to survive.

I decided to run away and a very kind family took me under their wing.

I kept studying, and after school I would spend some hours working at a hotel, where I met a family who were staying there as guests. I started talking about my life and they sympathised and they are my family to this day.

Image source, Claudio Yanez

Even though I was welcomed by this family I felt like a stranger, and it was hard trying to adjust to them, trying to adjust to this new environment. I wasn't used to any love, I wasn't used to any kindness.

You think you're guilty, it's your fault everything that happened to you as a child and as a youth. You carry this with you and it takes a lot to get rid of that.

You have to rebuild a new person. That took time, but eventually it happened.

Towards the end of university I started to feel more confident. I got a job, I'm a civil engineer and I'm now a high-ranking public servant.

I didn't share any of this with anybody until last year. People who've gone through what I've gone through are always discriminated against - it's like being branded and my country is a very bigoted and prejudiced country.

I didn't want the doors to be closed once I had revealed what I'd been through and what my origins were. That was my great fear, I did not want to be exposed.

Image source, Javiera AlbarrГЎn

But in light of recent revelations about the public care system in Chile, in which it came out that at least 1,300 children had died in the past 10 years under that system and many others have been mistreated or tortured, I decided to speak out about my past.

I thought that as a person who holds a high position and also as someone who has lived through all of that I should tell my story.

I've worked many, many years in the health sector and it very was surprising for my colleagues that this director, this manager had such a story, such an origin. I was really taken by the way they've reacted, it's been a very positive reaction. It's been very good for me and for them as well.

I have to accept that Chile has changed - it's a completely different country from the one I was brought up in - it's a more inclusive country and I think that's what's allowed my story to touch people.

Now I run a charity that helps children who are in this system. We're faced with children who have no motivation at all, children who've been told they're good for nothing, and we want to tell them that's not the correct way.

We want to make dreams come true and for those who don't have a dream we want to help them create a dream. Children can be whatever they want to be and we're there to help them be whatever they wish to be.

My mother, who was 63, passed away a couple of weeks ago, and, of course, it was sad. But I had suffered and cried over losing her already, during my childhood. She was never there for me and every time I was lonely or in pain I felt her absence. Maybe I needed a final conversation with her.

Claudio Yanez was speaking to Outlook on the ҙуПуҙ«ГҪ World Service

Join the conversation - find us on , , and .

Top Stories

More to explore

Most read

Content is not available