It was a mild November night. And in Berlin something unbelievable was happening.

Hundreds, and then thousands, of incredulous East Germans surged towards what was once an impassable divide and found they could cross it unchallenged.

Later, crowds cheered as young men with pick axes chipped away at the concrete that had separated them from the West for decades.

As they sang and lit candles, reporters, stiff in their overcoats, spoke into the cameras.

The Iron Curtain had parted. The Berlin Wall was falling. One of the defining moments of the 20th Century was underway.

And Angela Merkel went for her weekly sauna.

“It was Thursday,” she said many years later, “and Thursday was my sauna day so that’s where I went.”

Merkel did eventually venture to the West that night - and back again the following day - but she was in no rush.

“I figured if the Wall had opened it was hardly going to close again.”

The response was typical of the young quantum chemist. And her approach – unhurried analysis in the face of high drama – is one with which the whole world has become familiar.

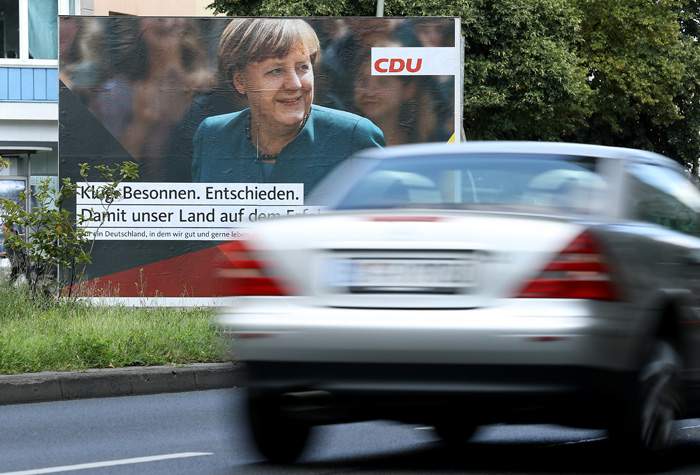

Angela Merkel is one of this century’s most enduring and powerful leaders - chancellor of Germany since 2005 and one of the world’s most recognisable figures.

Her strength has grown during Europe’s economic crises. And from her role as a conduit between Russia and the West. For many, Merkel represents stability in an unstable and shifting world.

Planning the future of a European Union without the UK. Quietly reinforcing new global alliances in the stormy wake of Donald Trump’s chaotic administration. Admirers declare her the last defender of Western democratic values. But while she is revered by many, she has also been reviled and caricatured for her uncompromising stances - on Greek debt, on refugee policy, on the environment.

And yet we know very little about her. Even in her own country, she remains an enigmatic figure.

The German chancellor is notoriously private. Her family, friends and staff are scrupulously discreet. Her husband, Joachim Sauer, makes few public appearances. The scientist is her second husband, although Merkel kept her first husband’s surname.

Merkel with her husband, Joachim Sauer

He and her confidantes form a circle around her as impenetrable as the thick forests of the Uckermark region where she grew up, and where she and Sauer still have a weekend retreat.

To understand Merkel, her politics, her motivation, it’s important to consider her rather unusual upbringing in what was then communist East Germany.

Her childhood home in Templin still stands - huge, serene, pastel-coloured, but overshadowed by the woodland that lies beyond it. To reach it one must drive through a complex of well-kept gardens and small cottages.

In the car park, a young man and woman greet visitors with a formal handshake delivered with a wide trusting smile.

Merkel's childhood home in Templin

They’re residents at the complex – it houses adults with learning disabilities, as it did during the then Angela Kasner’s childhood. Her father, a Lutheran pastor, moved his family here from Hamburg not long after Angela was born.

At a time when almost everyone else was migrating west, the Kasner family were heading east. The border had not yet been closed - that would come seven years later - but the regime in the communist German Democratic Republic was oppressive.

Those who were considered dissenters had few prospects. No-one’s really sure what motivated Reverend Kasner’s decision to come here but the job seems to have appealed to him and, as a member of the clergy, he would have enjoyed more freedom than most in East Germany.

“Both are there,” says Schöneich. “Her father was very career-focused and so is she. She acts tactically. Her mother is a very lovely woman who is loved by everyone.”

While her political strategy is, he says, like that of a good chess player, Merkel is also a politician of scruples.

“Many here expected that, when Angela became chancellor, Templin would blossom. You’re wrong, I told them, she can’t do that. She would be seen as biased.”

Merkel was 35 when the Berlin Wall fell. She’d had a university education, married and divorced in her 20s, and reportedly even lived in a squat at one point, but many other freedoms – including the ability to travel the world – had been denied to her generation.

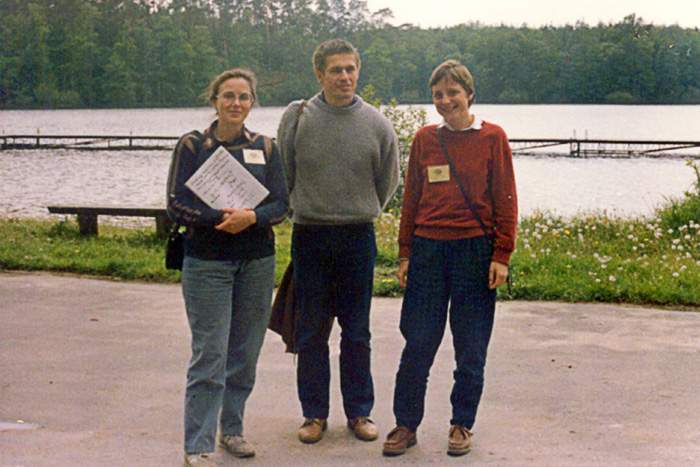

Merkel (r) pictured in Poland in 1989 with her husband, and her colleague Malgorzata Jeziorska

She often invokes her youth behind the Iron Curtain and speaks passionately on the subject of personal freedom.

After Donald Trump’s election, horrified by his plan to build a wall on the Mexican border, Merkel was quick to remind him of his duty to uphold Western values - “democracy, freedom, respect for the rule of law and human dignity” regardless of “ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation or political conviction”.

The girl from Templin was undoubtedly moulded by her country’s turbulent history. Merkel may not have been among those who, on that November night in 1989, stood next to the Wall and sang as it fell. But in the decades to come it would be her voice - as the leader of a new Germany - which would resonate across the world.

The environment minister was having a bad day.

A furious crowd had gathered. Shouting and jeering, the protesters waved their banners. There was no way anyone was sending reprocessed nuclear waste to their village.

Angela Merkel would struggle to persuade them otherwise. It was 1997 and she’d held the environment portfolio for three years. During that time, Helmut Kohl’s government had sent several transports of reprocessed waste from Germany’s nuclear power plants to be stored in or around the town of Gorleben.

The locals were not impressed. Neither was Germany’s environmental lobby. Some of the protests became violent. Thousands took to the streets. This was a national scandal and it would taint Merkel for years to come.

Angela Merkel in 1994

But she’d come a long way since she cast about for a political party to join after the Wall fell. In less than 10 years she’d gone from helping out in the office of the then-Democratic Awakening (which would later evolve into the modern day Christian Democratic Union) to party spokeswoman and was now rising through the ranks of Helmut Kohl’s cabinet under the tutelage of the chancellor himself. He referred to his protégée as his “mädchen”.

It was during those first years that Heiko Sakurai, a young political cartoonist, began to draw Angela Merkel.

“What I concentrated on were her eyes,” he says. “Half-closed eyes. How she was watching. That was interesting to me. I thought she’s a bit like a sleepy girl, insecure. But that has changed.

“I’m still drawing her with half-closed eyes but now I know it’s a sign of rationality. You can’t look into her mind - that’s still my problem. I still don’t know what the woman is thinking.”

Angela Merkel: You just let the men do it...

Theresa May: ... and then you get their job in the end.

It illustrates, in his view, an ability to keep secrets that may have been born out of necessity during her childhood in East Germany.

“That’s helped her in her career - to have a close circle of people who don’t talk and can keep secrets.”

Merkel’s mentor Helmut Kohl would learn – too late – just how secretive his protégée could be.

1994: Chancellor Helmut Kohl with Merkel

As Kohl and many in his party became mired in , Merkel distanced herself from him in a newspaper article. He never forgave what he perceived as an act of betrayal. Years later, his widow reportedly tried to stop Merkel from speaking at his funeral.

Merkel and Kohl in 2007: In his later years he was sometimes a critic of her policies

Merkel had helped to facilitate the end of Kohl’s chancellorship and had begun to realise her own ambition for the top job.

It was worthy of a plot from one of the Wagnerian operas Merkel so enjoys. A political transformation was underway. The mädchen - the little girl - was gone. In her place stood the mächtig - the mighty.

But, once her party regained power, it would be some time before Germany’s first female chancellor would gain the poise and self-assurance which characterise her today. Gradually her appearance changed - the hair cut less severe, the suits more streamlined.

The woman Germans initially came to call Mutti (mum) exuded, perhaps cultivated, an image as a safe pair of hands. Trustworthy, straightforward, careful. Despite the nickname - which is rarely used these days - Merkel’s gender has rarely been an issue. She has shattered a glass ceiling but it is rarely reflected in her own political rhetoric.

“There is in Germany,” says Wolfgang Bosbach, a long serving CDU MP, “a decades old advertising slogan which everyone knows and it applies to Angela Merkel too - It’s better to stick with what one has.

She’ll never stick to an ideology just for the sake of it, which is very un-German.”

“People know she doesn’t tend to extremes and she impresses many also with her personal life. I remember how [former French President Francois] Hollande was photographed at night on his scooter going to see his girlfriend. No one can imagine Angela Merkel at night on a moped going to see her lover - and it will never happen.”

But there have been moments where Merkel has surprised the country - and the world.

As Sakurai puts it: “She’s predictable but she’ll never stick to an ideology just for the sake of it which is very un-German. Germans are known to stick to their traditions and ideologies.”

For him, and for many, Merkel has deviated from her usual script twice.

Once when she announced the “energiewende” - her decision to end nuclear power in Germany following the crisis at the Fukushima plant in Japan in 2011. And, again in 2015, when she opened the country’s doors to hundreds of thousands of people.

Both decisions have defined her politically though at a cost to her reputation and popularity. Both decisions were applauded in some quarters but derided in others. Both had long term consequences.

Germany’s energy companies have sued the government over the “energiewende” - which means the last of their nuclear power stations will have to close by 2022. There will be compensation and tax refunds for some time to come.

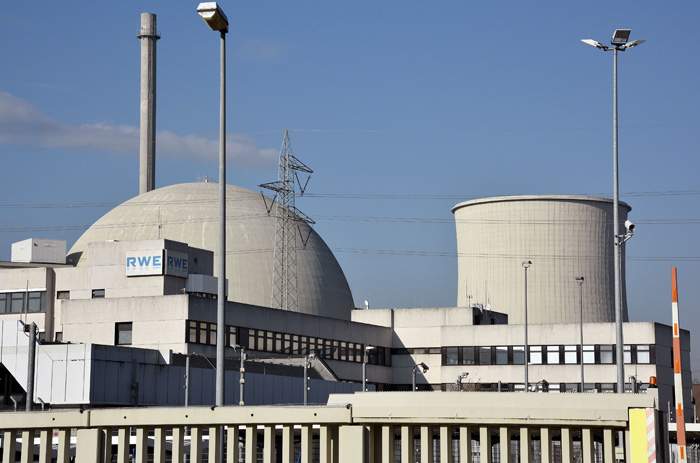

The owners of this German nuclear power station are seeking damages following the decision to close it

The administrative, social and financial burden of integrating hundreds of thousands of migrants into German society is impossible to quantify.

Perhaps those two decisions were all the more striking because Merkel is so carefully controlled – particularly when it comes to her public image. She is very funny – at off-the-record press briefings, she’ll answer questions with a twinkle in her eye, to a room filled with laughter. But it’s rarely seen on camera.

According to Wolgang Bosbach, Merkel "has a very good sense of humour..."

The first time they met, in his constituency, Wolfgang Bosbach asked Merkel if she wanted to go to the local fair.

"...but as soon as the cameras roll, you don’t see it.”

“She didn’t want to but then my children who were very small asked, so she couldn’t say no and with one child on her left, one on the right, they went to the fair, went on the carousel and she relaxed and enjoyed herself.

“When she relaxes she’s funny, she is witty,” says Bosbach. “Sometimes I feel she’s embarrassed when the public find that out about her. She has a very good sense of humour but, as soon as the cameras roll, you don’t see it.”

Bosbach also knows what it’s like to get on the wrong side of the German chancellor, having openly rebelled against her over the Greek debt crisis.

“The flaw she has is common in many who reach the very top. I saw it myself in Helmut Kohl. When someone like me has a different opinion and certain questions, be that the Greece crisis or the refugee problem, they question your loyalty.

“She finds it hard to accept when someone tells her ‘I have a different opinion but I will go into any battle for you’.”

Controversial subjects have come to characterise Merkel’s time in office – but they’ve also sustained it.

She is good at crisis management. Her growing strength on the world stage brought Germany itself into a powerful new position.

And these dramas drew focus away from those at home who grumble that she’s only ever reactive and rarely risks new policy. An unflattering verb entered the German lexicon in 2015 - “to Merkel”, which denotes indecisiveness.

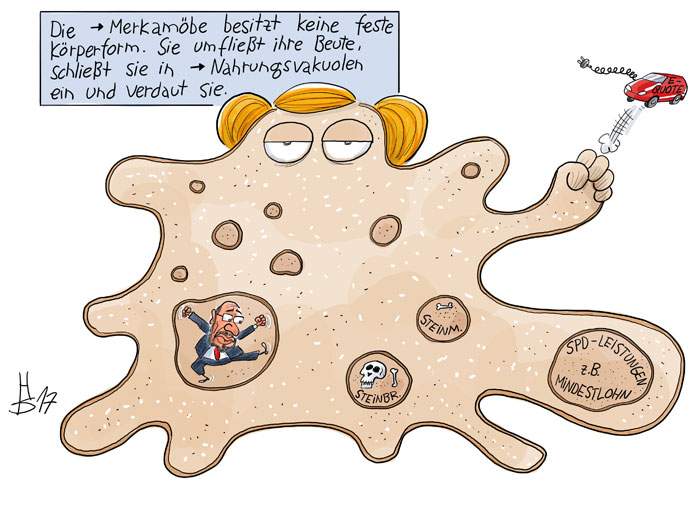

One of Sakurai’s most recent offerings presents Merkel as an amoeba, changing her political shape, swallowing up the ideas first presented by opposition parties.

"The Merkelamoeba has no fixed bodily form. She surrounds her prey, enclosing them in nourishment vacuoles and digests them."

“Her weakness is that I don’t know what her vision is. I don’t know if she has a vision for which way to lead the country. She’s reacting but she’s not acting.”

Neverthless, Sakurai says, after 12 years in office, “no-one underestimates her any more”.

The little blonde girl proudly lifted a cardboard box full of knitted toys. A tiny figure in the sprawling concourse of Munich railway station, she grinned, blue eyes shining. “They’re for the refugees!” she squealed, unable to contain her excitement. Around her a crowd of curious Germans smiled indulgently.

Minutes later, those refugees arrived. Scores of exhausted men, women and children, clutching grimy plastic bags and battered holdalls, trudging along behind a police escort.

For a moment the watching crowd was completely silent. Then someone began to applaud. Slowly the faces of the refugees brightened. The crowd, the cheers, the homemade welcome banners were all for them.

Angela Merkel had just taken the biggest gamble of her political career.

For months, the number of people seeking refuge in Europe from war, persecution and poverty had been steadily rising. Families clinging desperately to overcrowded boats in the Mediterranean or trudging along the verges of Europe’s motorways.

The EU now faced an unprecedented crisis and its leaders couldn’t agree how to deal with it. Merkel had already suspended the Dublin agreement - which requires asylum seekers to stay in their EU country of arrival - for Syrians.

But the Hungarian government had had enough. The authorities closed the main railway station in Budapest, refusing to allow asylum seekers to board trains onwards to Western Europe.

Perhaps Merkel was moved by the weary migrants chanting “Germany, Germany” outside Keleti station.

Or maybe it was the discovery, days earlier, of the decomposing corpses of 71 asylum seekers in the back of a lorry on an Austrian motorway. Police had been called by a road worker who’d spotted liquid seeping from the vehicle, abandoned on the hard shoulder of a motorway.

October 2015: Iraqi Kurdish men carry the body of one of 71 asylum seekers suffocated in an Austrian lorry

The men, women and children inside had trusted a gang of traffickers to get them to Western Europe. Instead they’d suffocated, packed together, standing room only, in the back of a meat transporter.

Merkel hastily agreed a plan with the Austrian government. Within hours, asylum seekers were joyfully boarding trains to Munich. The doors to Germany were open.

Afterwards, Merkel would say she’d acted to prevent a humanitarian crisis.

But, according to her former environment minister Norbert Röttgen, this was “not so much a moral or ethical question but – and this is typical for her – a decision based on facts. The refugees were there. Germany was able to deal with 10,000 refugees.”

Even so, he says, “collectively, Germany underestimated the longer term implications and consequences” of that decision.

As Röttgen puts it, “there was euphoria at first”.

Towns threw street parties to welcome the new arrivals, warehouses filled up with donated food and clothing, tens of thousands of volunteers staffed reception centres.

Germans revelled in their new international reputation. No longer defined by the echoes of World War Two or the caricature of the economic giant bullying the southern Eurozone. Instead, Germany was now the humanitarian face of Europe.

“Wir schaffen das!” Merkel proclaimed. We can do it. It was to become her motto, oft repeated over the coming year.

But her interior minister was worried, fearing a backlash. Without the goodwill of the volunteers, Thomas de Maiziere believed the country would struggle to cope with the sheer number of people now seeking asylum. Other EU countries were muttering furiously - Germany was encouraging the influx that affected them too.

Merkel repeatedly appealed for a quota system to evenly distribute asylum seekers across the EU. She was ignored.

As the months went by and towns and cities tried to house and integrate the hundreds of thousands of new arrivals, attacks on refugee accommodation were gleefully seized upon by her critics as evidence that her policy was failing.

Merkel’s approval ratings began to fall. As populist movements gained ground across Europe, Germany’s Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) campaigned hard and began to attract supporters.

“Wir schaffen das,” Merkel insisted. But her electorate were increasingly unconvinced.

For many, the real turning point came on the very last day of 2015. During New Year’s Eve celebrations in Cologne, hundreds of women were sexually assaulted by groups of men – mostly described as being of North African or Arab origin.

It horrified Germany. And, for the first time since the crisis began, Merkel was in real political trouble. Described at the time as a tired and isolated figure, even those loyal to her were in despair.

Demonstrators outside Cologne Cathedral protest at violence against women following the sexual assaults on New Year's Eve 2015

The Merkel brand became so tarnished that some within the party began to cast about for alternatives to lead them into the next general election. Their pessimism was vindicated as the party suffered two humiliating regional election defeats - one of them in Merkel’s own home state of Mecklenburg Vorpommen.

But, remarkably, she has survived.

Gradually her government has tightened the law - making it easier to deport asylum seekers who commit crime, as well as declaring countries like the former Balkan states safe so that their citizens have no right to asylum in Germany.

The number of migrants reaching Germany has dwindled. The deal Merkel brokered between Turkey and the EU helped.

Under its terms, migrants arriving in Greece would be sent back to Turkey. For every Syrian sent back, another Syrian in Turkey would be resettled in the EU. For playing its part, Turkey was promised millions of euros and visa free travel for Turkish citizens.

But in the end she also got lucky. Countries along the Balkan route slammed their doors shut. Merkel opposed this development but the closure of the Balkan route was a political lifeline.

A migrant camp in Lesbos Greece - numbers have dropped since a 2016 EU/Turkey deal

“At the last minute it stopped,” says Norbert Röttgen. “The numbers have decreased rapidly and significantly to a manageable level for the last 18 months. It was a critical period, but it turned out to not be a never-ending story.”

As Merkel predicted, the migrant crisis has changed Germany. And it’s perhaps too early to judge whether it’s for the better or the worse. Integration will take time.

There are success stories - the teams of migrants, exuberant in their cricket whites, teaching a hitherto unheard of sport to Germans, or the Syrian guides showing visitors around a museum of Middle Eastern antiquity. But there are still migrants living in poverty, housed in school gyms and unable - or unwilling - to access German language classes.

And there are unsettling stories too. The young woman volunteer killed by a Nigerian asylum seeker, or the crowd of Germans who clapped and cheered as a building designed to house refugees burned down in front of them.

Nevertheless, Merkel has never regretted the decision she made in the late summer of 2015 - although she’s made it clear that the year which followed will never be repeated.

If anything, Merkel said, she wished she’d acted sooner when Greece and Italy struggled single-handed to deal with the people arriving on their shores.

“It was,” she said in August 2017, “right and it was important for us to take these people in during this extraordinary situation.”

These days, her unwavering stance, and her continued insistence that Germany did the right thing, appears to help rather than hinder her popularity.

Merkel seems to have got away with it. But perhaps more by luck than judgement.

The two giant pandas chewed impassively on their bamboo, apparently oblivious to the global significance of the piece of diplomatic theatre being performed right in front of their new enclosure at Berlin Zoo.

Meng Meng and Jiao Qing are on loan from China. Germany is paying $1m a year for the privilege of hosting the bears. Don’t be fooled by their names – which translate as “sweet dream” and “darling” - the animals symbolise strength and unity.

Merkel and Xi Jinping open the panda enclosure at Berlin Zoo

And the timing of this piece of panda diplomacy couldn’t have been more carefully stage-managed. Angela Merkel and the Chinese president, Xi Jinping formally opened the enclosure together – just days before they faced Donald Trump across the G20 summit table in Hamburg.

The German chancellor had already helped to secure China’s ongoing commitment to the Paris climate accord, after the Trump administration announced it would pull out. In the preceding weeks she’d also taken the rather unusual step of hosting the Indian prime minister and the leaders of the EU member countries for pre-summit talks.

After the twin shocks of Brexit and Donald Trump’s election, Merkel has been seeking to create stability and perhaps new partnerships in this new world. It will change her own and her country’s role on the international stage.

She warned that Europe could no longer rely on the traditional alliances with Britain and the US.

“The times in which we could completely depend on others is, to an extent, over,” she told voters at a rally in Munich. “We Europeans have to take our fate into our own hands.”

Speaking in Munich, May 2017: "We... have to take our fate into our own hands"

Merkel‘s clout on the world stage sprang initially from her own country’s economic weight and subsequent leadership during the Eurozone crisis. Her stance earned her admirers and critics but, as Konstantin von Hammerstein and Rene Pfister wrote in Der Spiegel in December 2012, there was no doubting her power.

“All eyes in Europe are directed at Merkel. No other politician on the Continent arouses as many hopes - or as much hatred - as the German chancellor. When she visits Greece, protesters wearing Nazi uniforms march through the streets of Athens, and yet a word from Merkel can also mean saving a euro country from bankruptcy.”

A 2012 protest in Athens against EU austerity measures depicts Merkel as Hitler

The crisis cemented Merkel’s position as de facto leader of the EU. But two relationships were crucial to a more powerful global position - one to the east and one to the west.

The story of one of Merkel’s meetings with Vladimir Putin is well-known and often repeated. During talks, Putin allowed his black Labrador Connie despite knowing that the German chancellor had a profound fear of dogs. The Russian leader later apologised but over the years the story has come to symbolise a fractious relationship.

Putin allowed his labrador into the room where he was meeting Merkel, despite her fear of dogs

The leaders share a grudging respect for one another. They also share a history. She grew up in East Germany where she learned to speak Russian. He was stationed in Dresden, in the east, and speaks German.

Merkel is credited with brokering regular talks over Russia’s activities in Ukraine, with France the fourth partner in the so-called Normandy format.

Critics argue that the terms of the have never actually been met. But by intervening to stop the US sending weapons to Ukraine, for example, it has been argued that Merkel has limited some of the bloodshed.

The format of the talks also illustrated her perceived status as a link between Russia and the West and, in particular, the US.

When Merkel discovered in 2013 that to her mobile phone, she was furious. “Spying on friends,” she said at the time, “that’s just not on.”

But the revelation did little to sour her relationship with then-President Barack Obama and the two leaders fostered a warm, trusting and mutually beneficial relationship, speaking frequently over the phone.

Barack Obama with Merkel in Berlin, May 2017

She supported and advised the president who, at the time, had little real domestic power. And President Obama, who enjoys rock star status in Germany, and is as popular among many Germans as his successor is reviled, reciprocated.

In April 2016, well before Donald Trump’s election, a survey for die Zeit newspaper found that nearly two-thirds of Germans (62%) regretted the fact that Obama couldn’t serve another term. In May 2017, 70,000 people cheered and chanted his name as Obama stood in front of the Brandenburg gate and told the crowd: “We can’t hide behind a wall.”

His friendship with Merkel, and his public support for her refugee policy, has done much to soothe her voters. The two leaders were unable to push through the doomed US/European trade deal TTIP but they did build a transatlantic alliance which bound Europe and America together.

It’s a partnership unlikely to be replicated with the new administration. Merkel initially decided the way to Donald Trump’s heart was via trade, with the chief executives of Siemens and BMW.

Merkel and Trump at the G20 meeting in Hamburg, July 2017

Then she tried the family route, appearing on stage alongside his daughter Ivanka at a women’s business event in Berlin. Behind the scenes, advisers spoke – without much conviction - of a new style of transatlantic diplomacy. But, one confided, it was like dealing with a five-year-old.

With Ivanka Trump at a women's business event in Berlin

Merkel’s strength now may depend on her opposition to Trump’s rhetoric.

“She relies on her immense reputation as one of the world’s longest serving leaders,” says Wolfgang Bosbach. “Others have come and gone but Angela Merkel stays and she also relies on her strong nerves, her poker face. You can’t really tell from her expression which way she’s going to decide, she’s not extrovert, she’s not a big tweeter like Donald Trump but that doesn’t mean that she isn’t completely focused on her political goal.”

That poker face slips occasionally, particularly when it comes to the UK, where Merkel - and most Germans - have a profound fondness. On 24 June 2015 Merkel’s spokesman tweeted footage of the world’s most powerful woman showing one of its most famous women around her office.

Merkel gives the Queen a tour of her offices, 2015

Merkel, speaking in English, which she rarely does in public, points out the former course of the Berlin Wall and her former home in the old East to the Queen. Viewed now, the footage has a certain poignancy.

A year later to the day a visibly shocked Merkel would speak – this time in German – of her great sorrow at Britain’s decision to leave the EU.

She, like many Germans, was completely flummoxed by the result of the 2016 referendum.

24 June 2016: Merkel arrives at a press conference to give her reaction to the UK referendum

In a country where people identify themselves as European first and German second, the EU represents an ideal of post-war unity. While not without imperfections and challenges, the institution is

Aware of the situation in the UK before the vote, Merkel showed willing, suggesting that she wouldn’t rule out treaty changes in the future, saying “where there’s a will there’s a way”, but in reality her position has never changed.

With former British Prime Minister David Cameron - the two reportedly had a warm personal relationship

There would be, she emphasised time and again, no access to the single market without the free movement of people.

Confronted by Britain’s decision to leave the EU, Merkel’s initial reaction was to present a united front.

Within days of the Brexit vote EU foreign ministers, and then the leaders of France and Italy, held meetings in Berlin. By 2017, when Brexit negotiations began, that united front was still in evidence.

Germany under Merkel won’t break away from the official EU position. And she’s the one setting the tone.

She never wanted to go down in the history books as the German chancellor under whom Britain left the EU

It’s based on the desire to satisfy two principles. To keep Brexit as clean as possible - Britain is an important partner and a break which damages its economy will adversely affect Germany too. But the terms of the British departure cannot be so generous that they risk encouraging other countries to leave too.

If anything, Brexit – or at least dealing with the fallout - has strengthened Angela Merkel domestically. But, as one commentator noted, she never wanted to go down in the history books as the German chancellor under whom Britain left the European Union.

Koblenz is a city where two great European rivers meet. The very name of this ancient settlement originates from the confluence of the French Moselle and the German Rhine. And it was here, in January 2017, that hopes of a very different union briefly flared.

To flashing lights and loud music, flanked by their country’s flags, the giants of Europe’s right-wing, Marine Le Pen and Geert Wilders, marched through a crowd of cheering supporters and on to a stage where they were joined by Frauke Petry, then leader of Germany’s own populist movement, Alternative für Deutschland.

(l-r) Geert Wilders, Frauke Petry and Marine Le Pen meet in Koblenz, January 2017

What began life as an anti-euro party on Germany’s political fringe, then evolved into a right-wing movement which gathered pace and support during the migrant crisis. Its xenophobic rhetoric and nationalist fervour repulsed many Germans. Nevertheless its anti-migrant and anti-Islam stance appealed to those perturbed by Angela Merkel’s refugee policy. There was a broader appeal too. AfD began to attract voters who felt forgotten, even ignored by Germany’s centrist politics and mainstream parties.

Donald Trump had just been elected when the Koblenz meeting took place. The EU was still digesting the shock of Britain’s decision to leave. Le Pen and Wilders sensed triumph. A patriotic spring was underway, they declared. This unstoppable force would revolutionise Europe.

Beyond the police cordon, protesters demonstrated against this so-called summit of the right (from which the mainstream German press had been banned).

Protesters demonstrate outside the Koblenz event

But away from the conference hall, the Moselle continued its quiet and endless flow into the Rhine.

There is little appetite for revolution here. Post-war Germany is, by and large, a philosophical nation, which tends towards compromise and distrusts impetuous decision making.

No wonder perhaps that its leader, who embodies those qualities, has lasted for so long.

Merkel has been in the job for 12 years. Her political fortunes have risen, fallen and risen again. But her personal popularity rating - measured monthly for broadcaster ARD - has never dropped below 46%. That’s part skill and part fortune.

Ever since the Brexit referendum and Trump’s election, Merkel, to many German voters, is a stable figure in an unstable world.

She took her time deciding whether to stand for a fourth term, admitting that she was torn. Exhausted by the migrant crisis, unsure of the electorate’s support, she also, Ulrich Schöneich says, wanted to spend more time with her elderly mother.

At the time, some suspected her of deliberate prevarication - and it wasn’t long before her party, and the country, started to feel mildly panicked.

There is no obvious successor to Merkel. To coin the phrase often employed by Merkel herself to defend her nuclear and economic policies, Germany found itself “alternativlos” (without alternative).

This may not be entirely accidental. As Schöneich notes: “She learned her lesson from Kohl who would not tolerate anyone being at his level. She managed to get rid of all the men with ambitions to her job.”

At the age of 63, Merkel is unrivalled and at the height of her political confidence.

Merkel is also preoccupied by, and expected by many to shape, the future of a post-Brexit EU.

She has indicated support for French President Emmanuel Macron’s ambition for deeper integration within the Eurozone, although hopes for a renewed Franco-German axis at the heart of Europe are fading somewhat as Macron’s domestic popularity leaches away.

Merkel has indicated support for her new French counterpart, Emmanuel Macron

But the international stateswoman must please her home crowd too. She knows she barely survived the migrant crisis - voters want a clear integration and asylum policy. The scandal over bypassing tests on diesel cars casts a shadow still. Air pollution regularly exceeds legal levels in many German cities and at least one, Stuttgart, may impose a ban on all diesel vehicles.

Merkel must protect the health of her citizens but she must also safeguard Germany’s automobile industry.

And, as Wolfgang Bosbach puts it, Merkel has a tough challenge ahead - “future-proofing” the economy in a globalised marketplace.

Many wonder how much longer she will continue. Will she see out a fourth term? Bosbach believes so. After all, he says, the chancellor is motivated solely by a sense of duty.

“She understands her role as being a servant of the state. She grew up in East Germany, far removed from democracy, which is why she perceives her life in reunited Germany as a gift and she wants to show gratitude to this country and give back in return for the freedom and rights she received after the Wall came down.”

It’s not clear whether the far-right leaders who gathered in Koblenz at the beginning of 2017 realised that they were meeting not far from the city’s most famous landmark. A huge statue of Kaiser Wilhelm I on his horse was built there in the 19th Century to commemorate the celebrated emperor who unified Germany.

Those who promised a patriotic spring here never fully realised their ambitions. Marine le Pen and Geert Wilders were defeated at the ballot box, although the AfD has gained a significant number of seats in the federal German parliament.

Kaiser Wilhelm still stands, implacable. Beneath him the rivers flow, slow and constant. And, quietly, in her office in Berlin, Angela Merkel gets on with her job.