The Cassini satellite has almost run out of fuel.

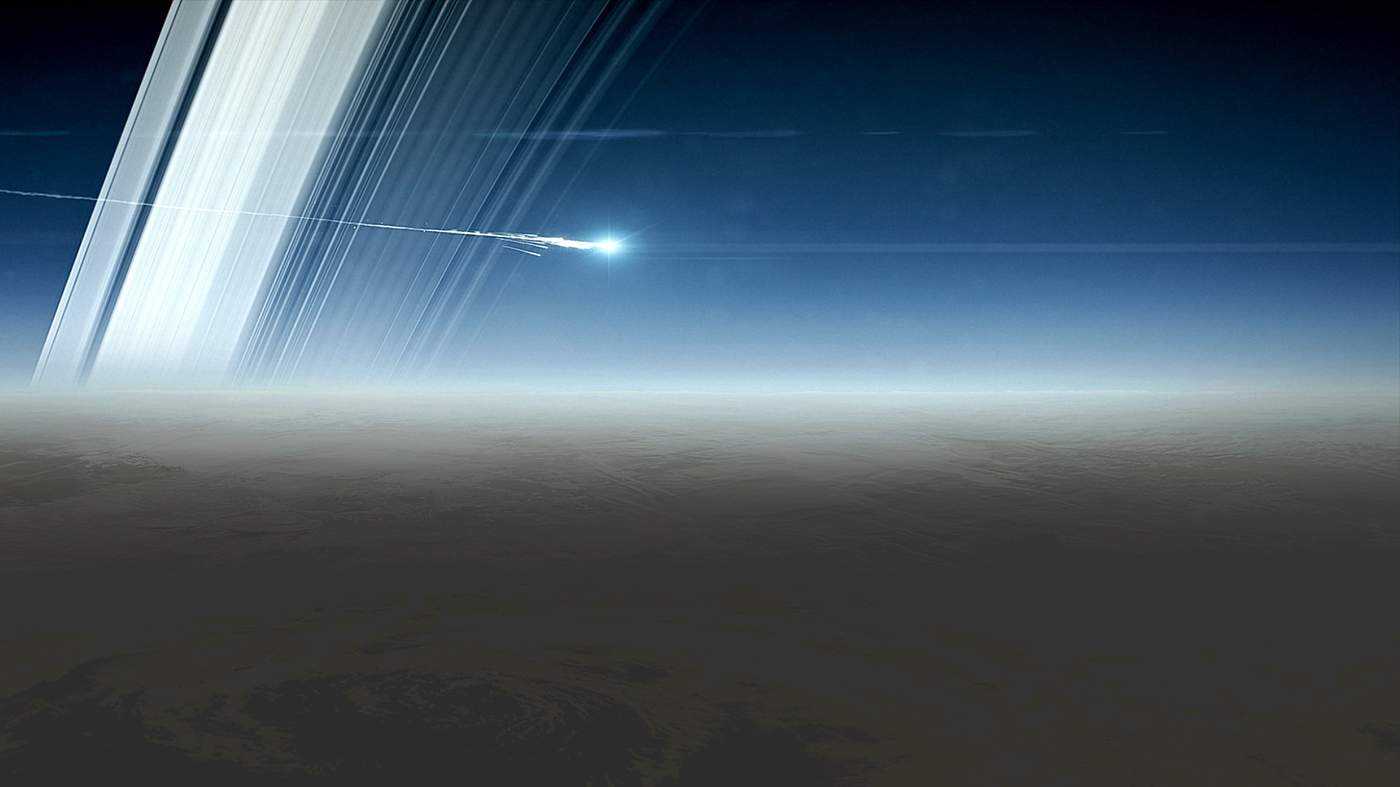

Its final mission, on 15 September, is to dive into the planet's thick atmosphere, where it will meet a fiery end.

An encounter with the moon Titan has nudged Cassini's trajectory on to a collision course with Saturn. Nasa has called this manoeuvre a “goodbye kiss”.

For 13 years, the orbiter has been sending back to Earth images of its extraordinary discoveries at Saturn.

It has documented the possible birth of a moon, tasted an extra-terrestrial ocean and watched as a giant storm encircled the entire planet.

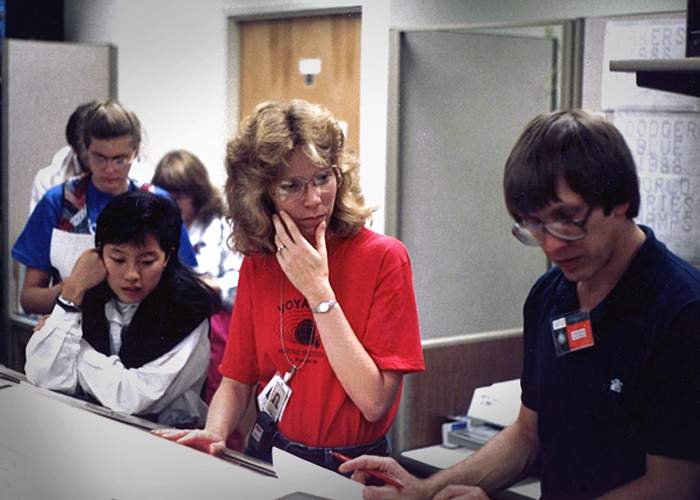

Linda Spilker will be there to wave it off.

“For me, when I first started working on Cassini in 1988, my oldest daughter Jennifer had just started kindergarten. And now, here we are in 2017, she's married and she has a daughter of her own,” says Dr Spilker, project scientist for the Cassini mission.

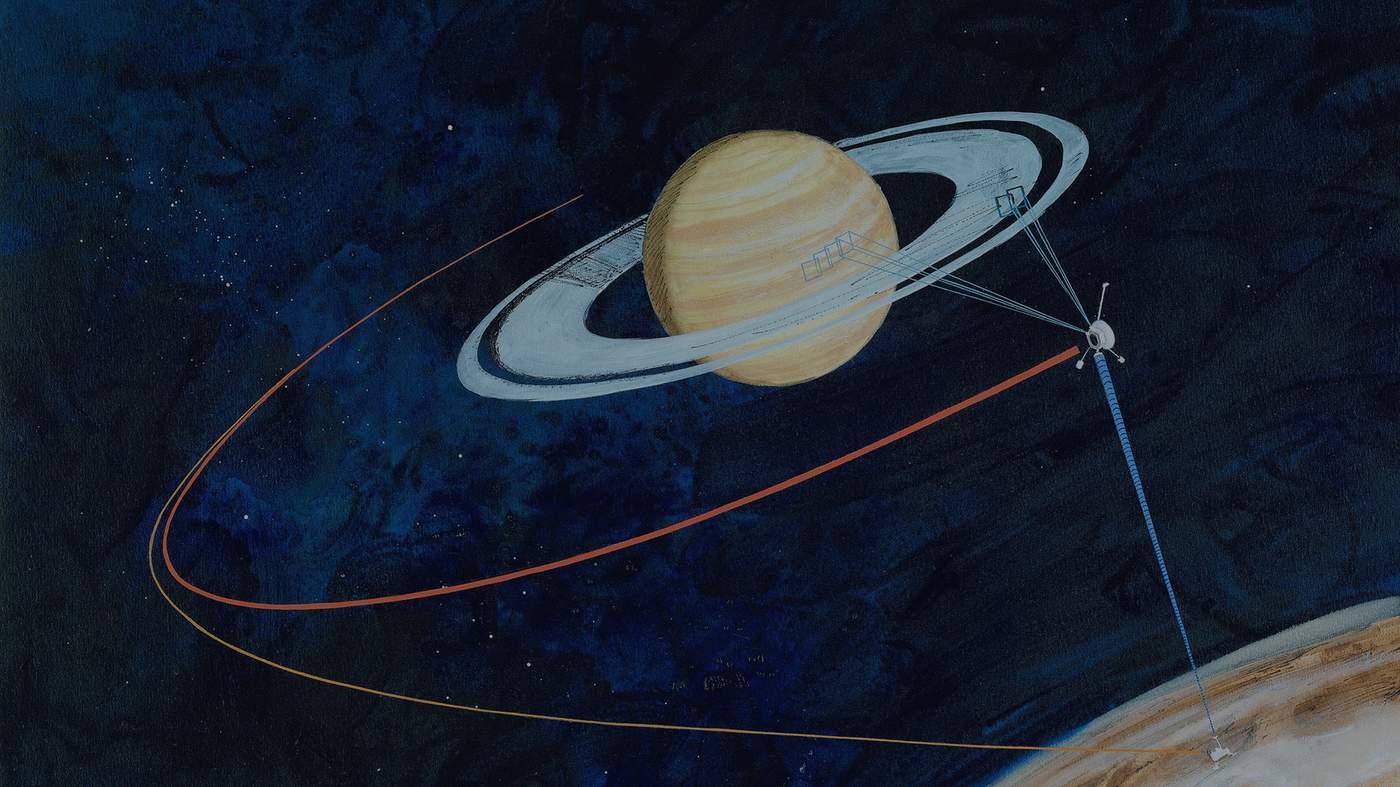

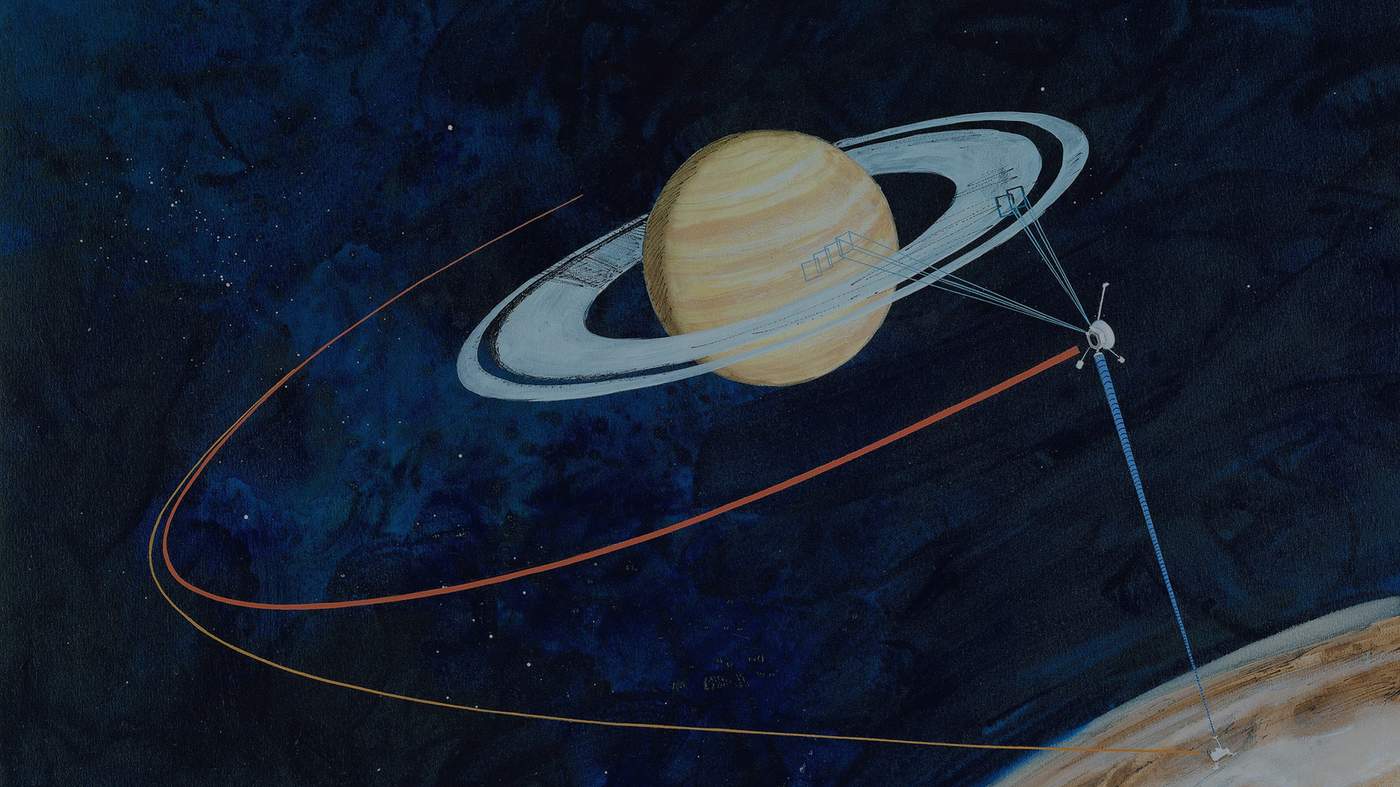

Computer animation - known as the “ball of yarn” - showing all of Cassini's orbits of Saturn

(Nasa)

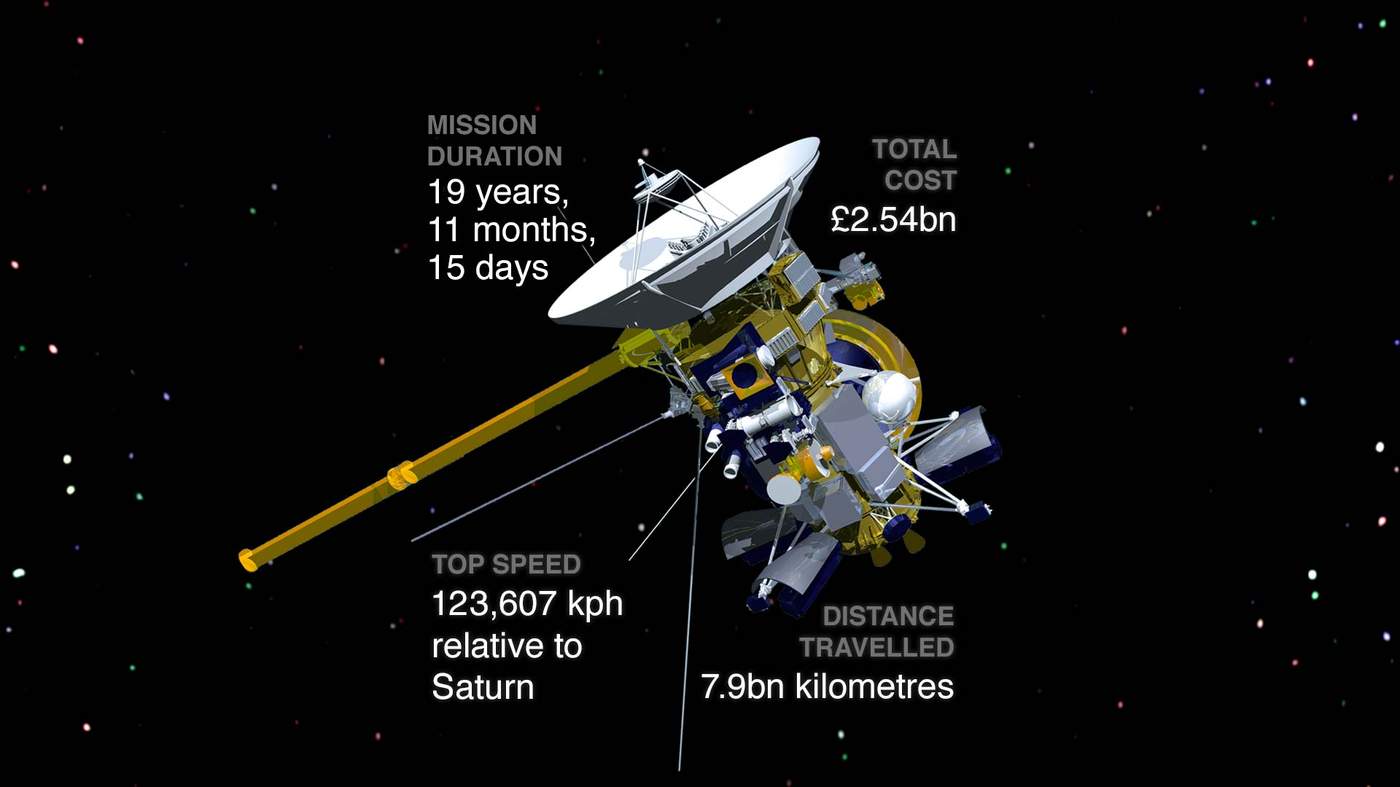

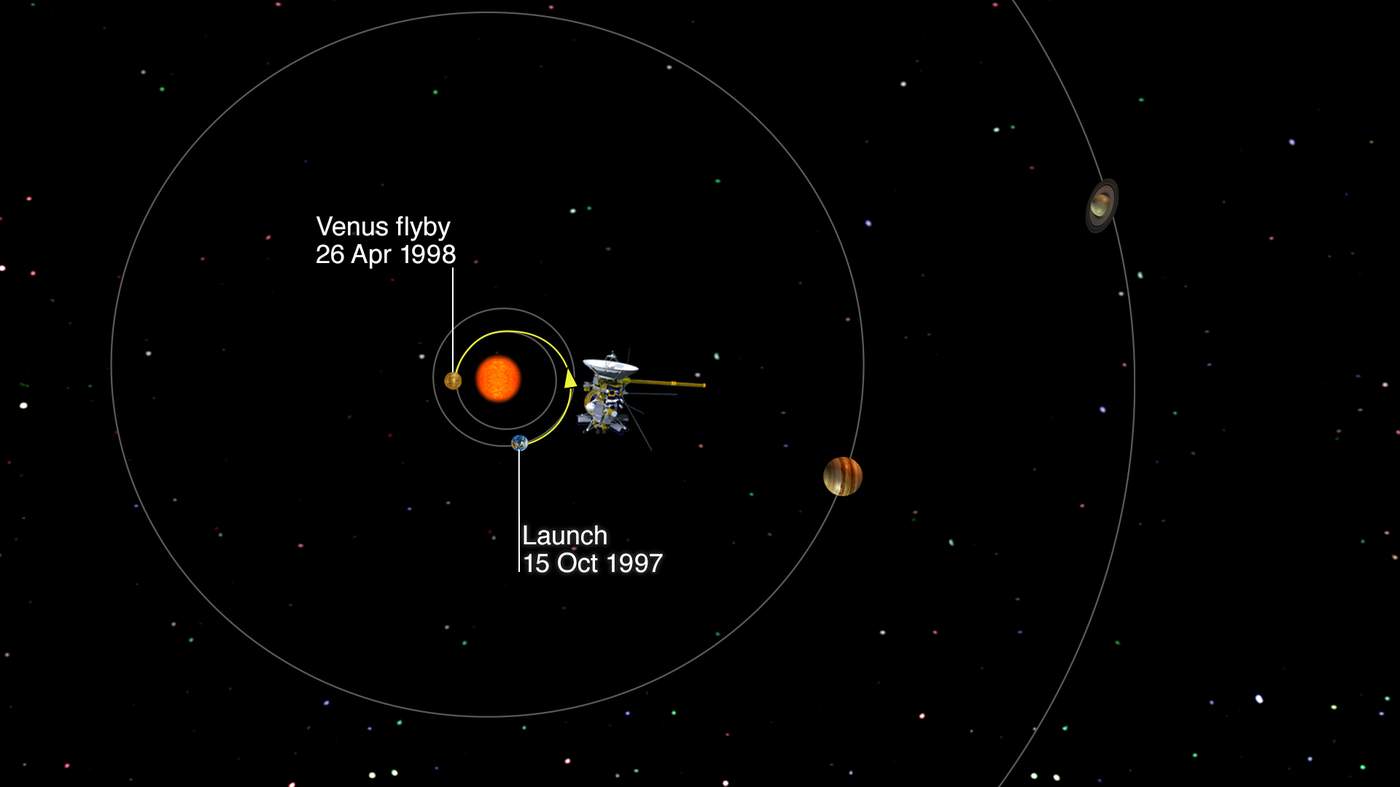

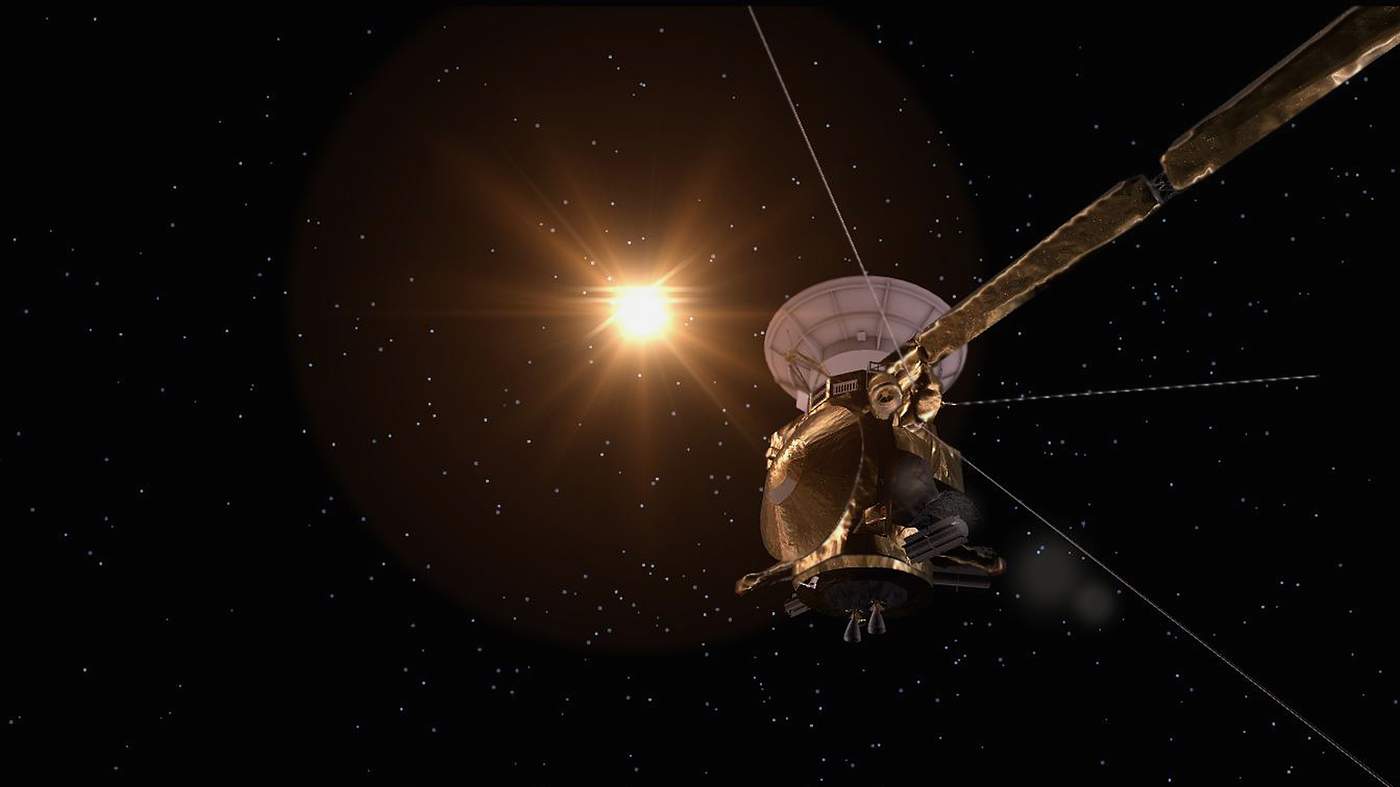

The mission set off from Earth in 1997 to explore the giant ringworld and its menagerie of moons.

After joining the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in 1977, Dr Spilker worked on the Voyager missions to the outer Solar System.

She describes herself as a “Voyager mom”.

“My two children were born, very strategically, in a window on Voyager between the Saturn and Uranus flybys, because there were five years between them.”

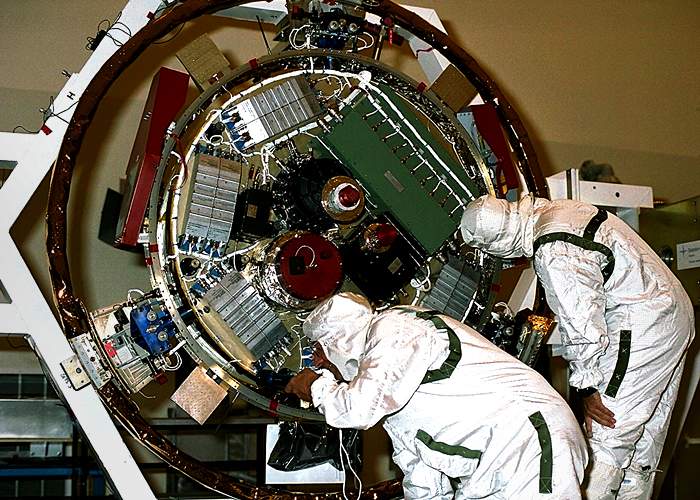

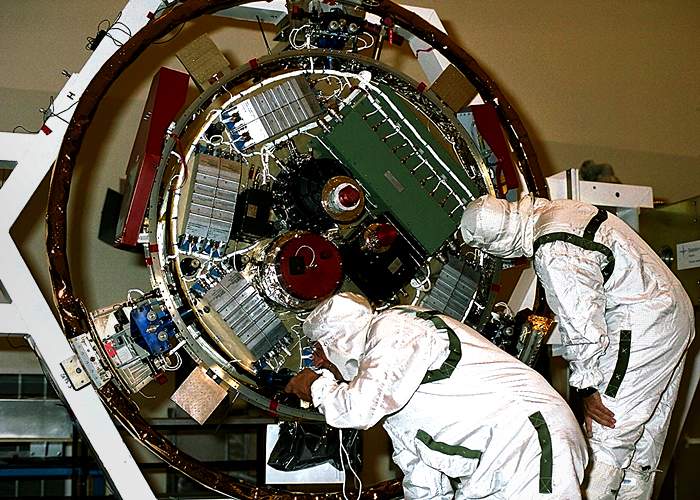

Cassini-Huygens in a Nasa test chamber before launch, 1997

(Nasa)

With Cassini proceeding apace, Dr Spilker's attentions were turned to Saturn full-time.

There were originally two spacecraft: Cassini and Huygens, which travelled to Saturn attached to one another.

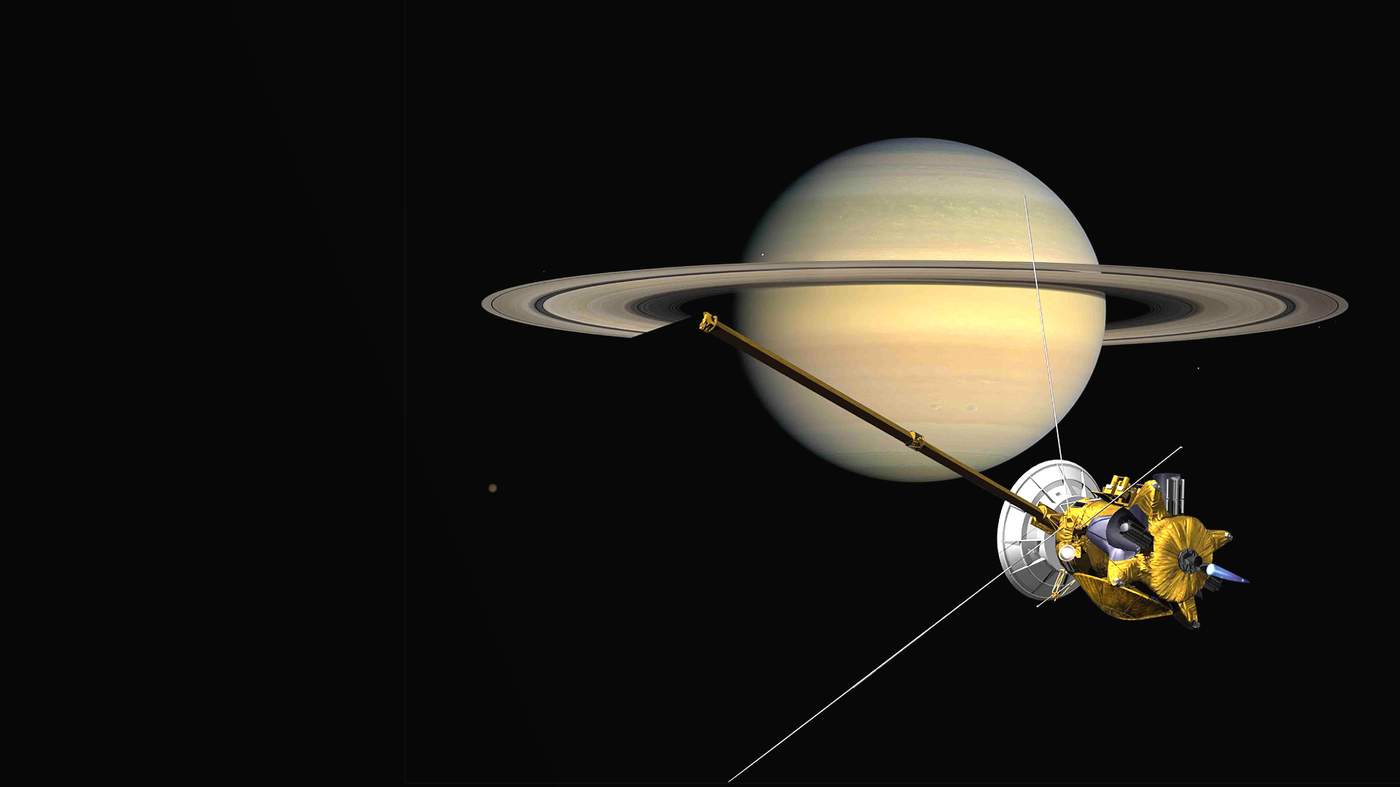

Cassini is the American orbiter, which has been exploring Saturn since 2004.

Huygens was a European landing probe, released from the Cassini “mothership” shortly after arrival in Saturn's orbit.

In January 2005, Huygens descended through the atmosphere of the saturnian moon Titan, sending back information about its environment.

A fascination with Saturn’s magnificent rings led Linda Spilker to join Cassini-Huygens when it was still on the drawing board.

She has been with the mission ever since.

Linda Spilker in 1989

(Nasa)

But Dr Spilker isn’t the only one - several members of the team have worked on the mission for the best part of a decade or longer.

Their families have been on holiday together and, in some cases, their children have grown up with each other.

The data that the spacecraft has sent back to Earth has been transformative.

“Cassini has been insanely, wildly, beautifully successful,” Nasa program scientist Curt Niebur said recently.

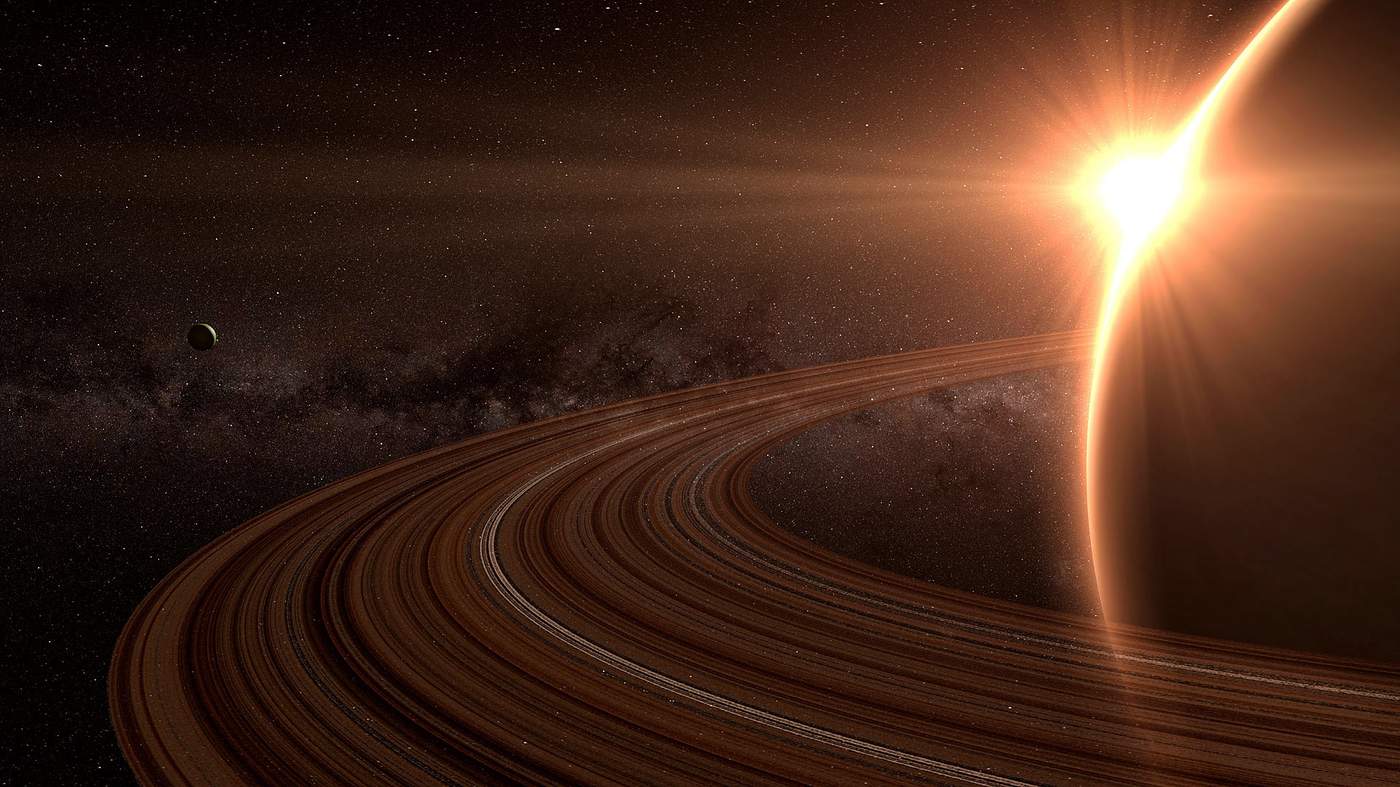

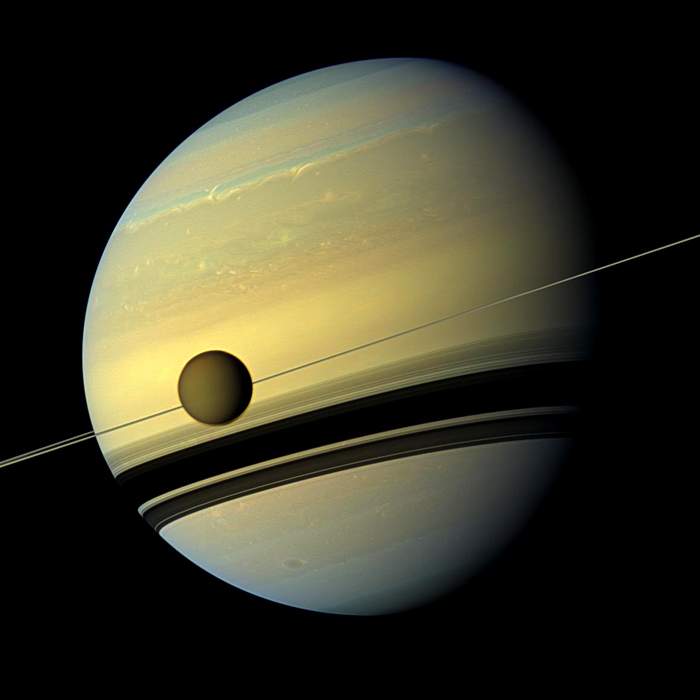

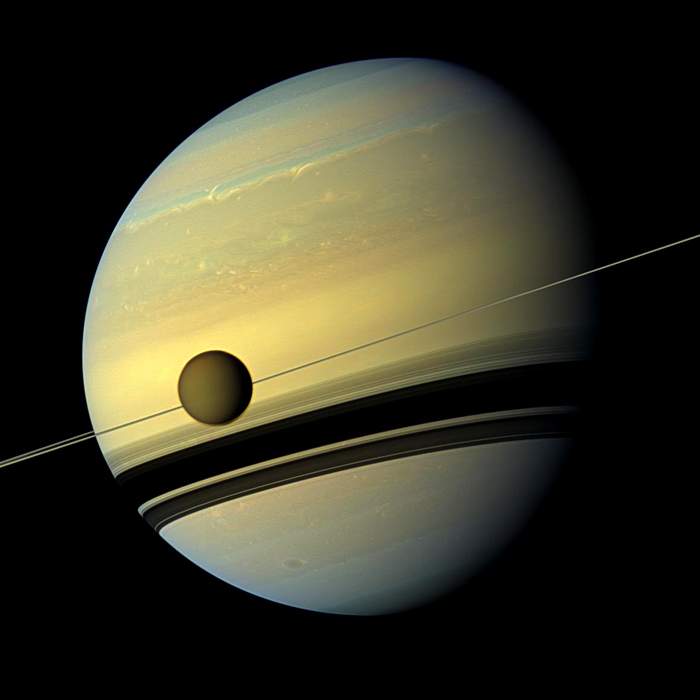

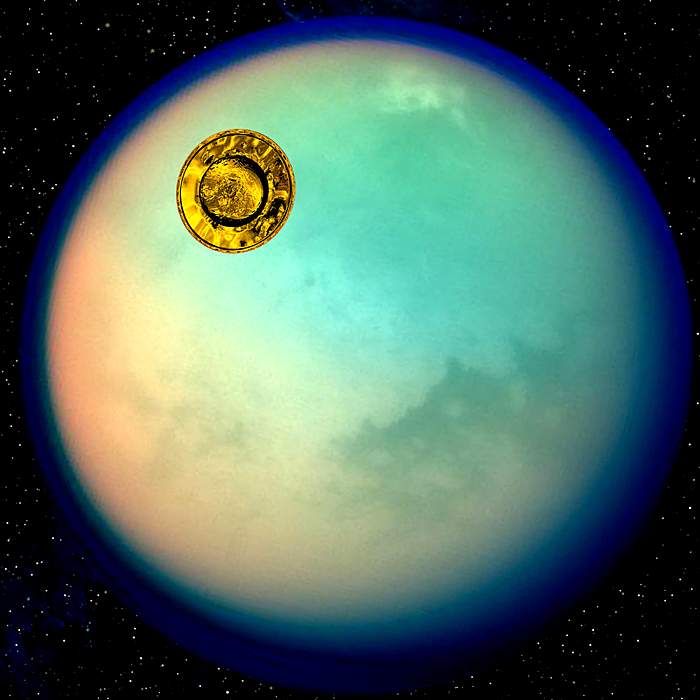

Cassini's view of Saturn and its moon Titan

(Nasa)

Saturn’s majestic rings have been revealed as a time machine, a kind of mini-Solar System and a laboratory for studying how planets and moons are formed.

We also discovered that Titan has wind, rivers, seas and lakes, just like Earth - but with an exotic twist.

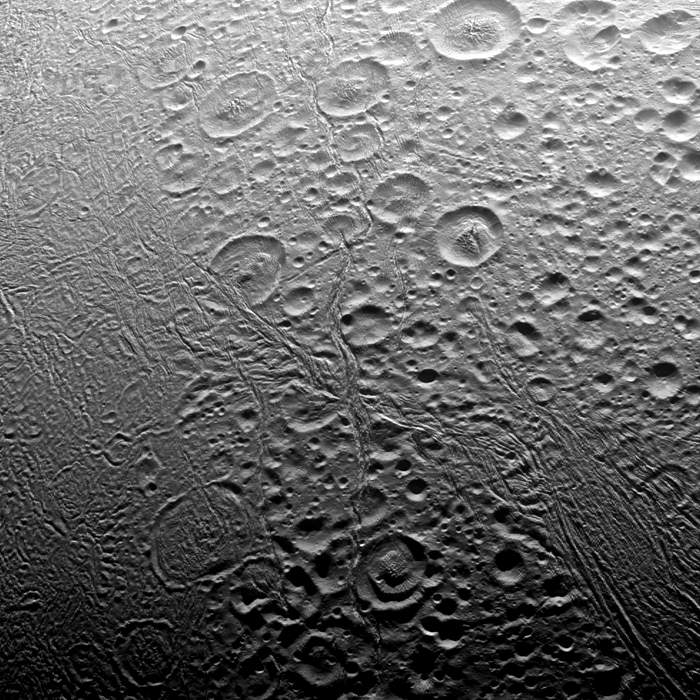

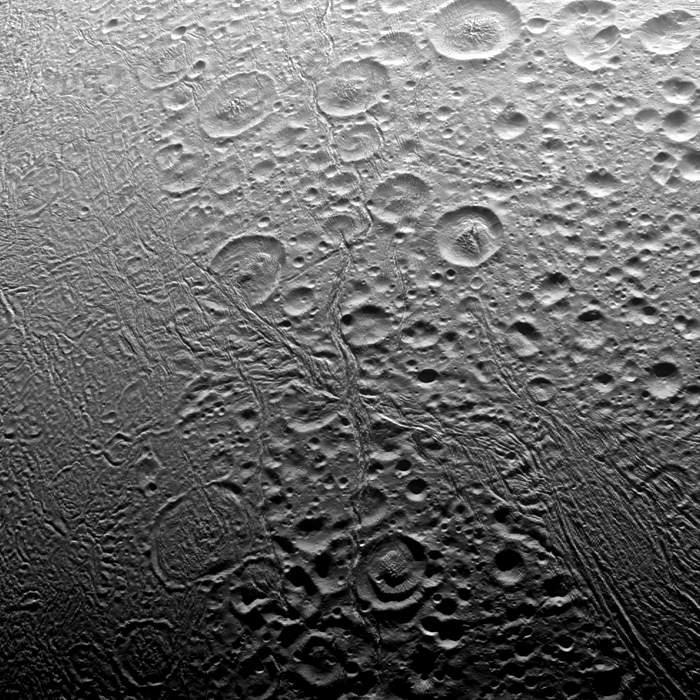

And through Cassini’s flybys of the enigmatic moon Enceladus, we found that many of the Solar System’s icy moons could be hiding deep oceans of water beneath their surfaces.

The surface of Enceladus seen by Cassini

(Nasa)

As such, there could be footholds for life all over our cosmic neighbourhood - something that could have profound implications for our own place in the Universe.

But the mission’s prospects hadn’t always looked rosy. In fact, at the turn of the millennium, mission planners were faced with the prospect of an unmitigated disaster.

They had already launched the spacecraft to Saturn when a fatal flaw was discovered.

Huygens, the probe designed to land on Titan, would not be able to “talk” to its mothership Cassini during the descent to Saturn’s biggest moon.

All useful data would be lost, and years of hard work would be consigned to the rubbish bin.

Work on the Huygens probe before it was attached to Cassini

(Nasa)

“There was a sense of urgency, of importance. This was clearly one of the prime components of the mission and we had to salvage everything we could,” says Cassini’s program manager Earl Maize.

Racing against the clock, scientists and engineers worked day and night to solve the problem. Eventually, an ingenious fix was found.

It was just one of many examples across the mission's 35-year history where ingenuity and international co-operation helped overcome daunting obstacles.

The data that the spacecraft has sent back to Earth has been transformative.

“Cassini has been insanely, wildly, beautifully successful,” Nasa program scientist Curt Niebur said recently.

Cassini's view of Saturn and its moon Titan

(Nasa)

Saturn’s majestic rings have been revealed as a time machine, a kind of mini-Solar System and a laboratory for studying how planets and moons are formed.

In addition, we've discovered that Titan has wind, rivers, seas and lakes, just like Earth - but with an exotic twist.

And through Cassini’s flybys of the enigmatic moon Enceladus, we found that many of the Solar System’s icy moons could be hiding deep oceans of water beneath their surfaces.

The surface of Enceladus seen by Cassini

(Nasa)

As such, there could be footholds for life all over our cosmic neighbourhood - something that could have profound implications for our own place in the Universe.

But the mission’s prospects hadn’t always looked rosy. In fact, at the turn of the millennium, mission planners were faced with the prospect of an unmitigated disaster.

They had already launched the spacecraft to Saturn when a fatal flaw was discovered.

Huygens, the probe designed to land on Titan, would not be able to “talk” to its mothership Cassini during the descent to Saturn’s biggest moon.

All useful data would be lost, and years of hard work would be consigned to the rubbish bin.

Work on the Huygens probe before it was attached to Cassini

(Nasa)

“There was a sense of urgency, of importance. This was clearly one of the prime components of the mission and we had to salvage everything we could,” says Cassini’s program manager Earl Maize.

Racing against the clock, scientists and engineers worked day and night to solve the problem. Eventually, an ingenious fix was found.

It was just one of many examples across the mission's 35-year history where ingenuity and international co-operation helped overcome daunting obstacles.

The plan to return to Saturn with a dedicated mission was hatched after the Voyager probes beamed back stunning images of the outer planets and their moons.

Voyager 1 colour-enhanced image of Saturn

18 October 1980

(Nasa)

“The Voyagers gave us a really wonderful impression of Saturn. It’s a beautiful gas giant,” says Nasa’s director of planetary science Jim Green.

Prof Andrew Coates, from the Mullard Space Science Laboratory in Surrey, UK, agrees:

“Saturn is the most spectacular planet in our Solar System. The incredible rings, visible even in binoculars or a small telescope, make it stand out compared to all the rest.”

In places, the rings are only about as tall as a telephone pole. Yet from end-to-end they are more than 20-times as wide as the Earth.

They have influenced decades of science fiction book covers.

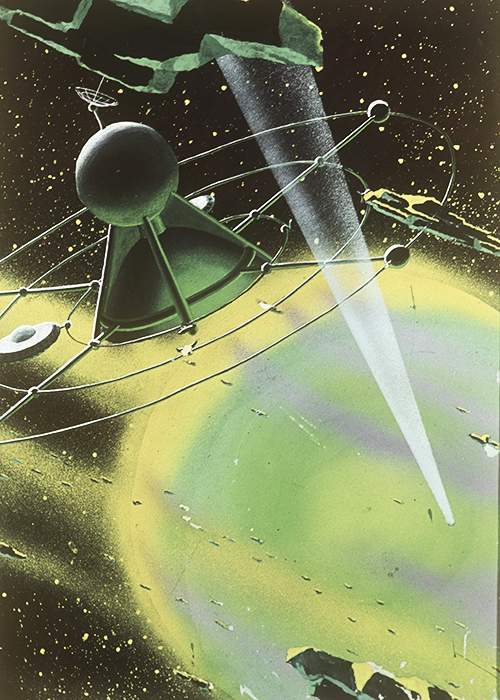

Reproduction of “In the Ring of Saturn” by artist Andrei Sokolov

(Topfoto)

Then there is Saturn’s biggest moon - Titan.

This world was thought to be a deep frozen version of Earth, but was shrouded in a dense orange haze that previous missions hadn’t been able to see through.

“It’s a fabulous moon. It’s a huge moon. If you pulled it out of orbiting Saturn and had it orbit the Sun, you’d call it a planet. It’s bigger than the planet Mercury,” says Green.

In the early 1980s, Nasa cancelled a collaborative mission with Esa, leading to frosty relations between the two organisations.

Though scientists continued to work on the Saturn mission regardless of politics, they would eventually need their space agencies to buy into a transatlantic partnership if they had a hope of launching.

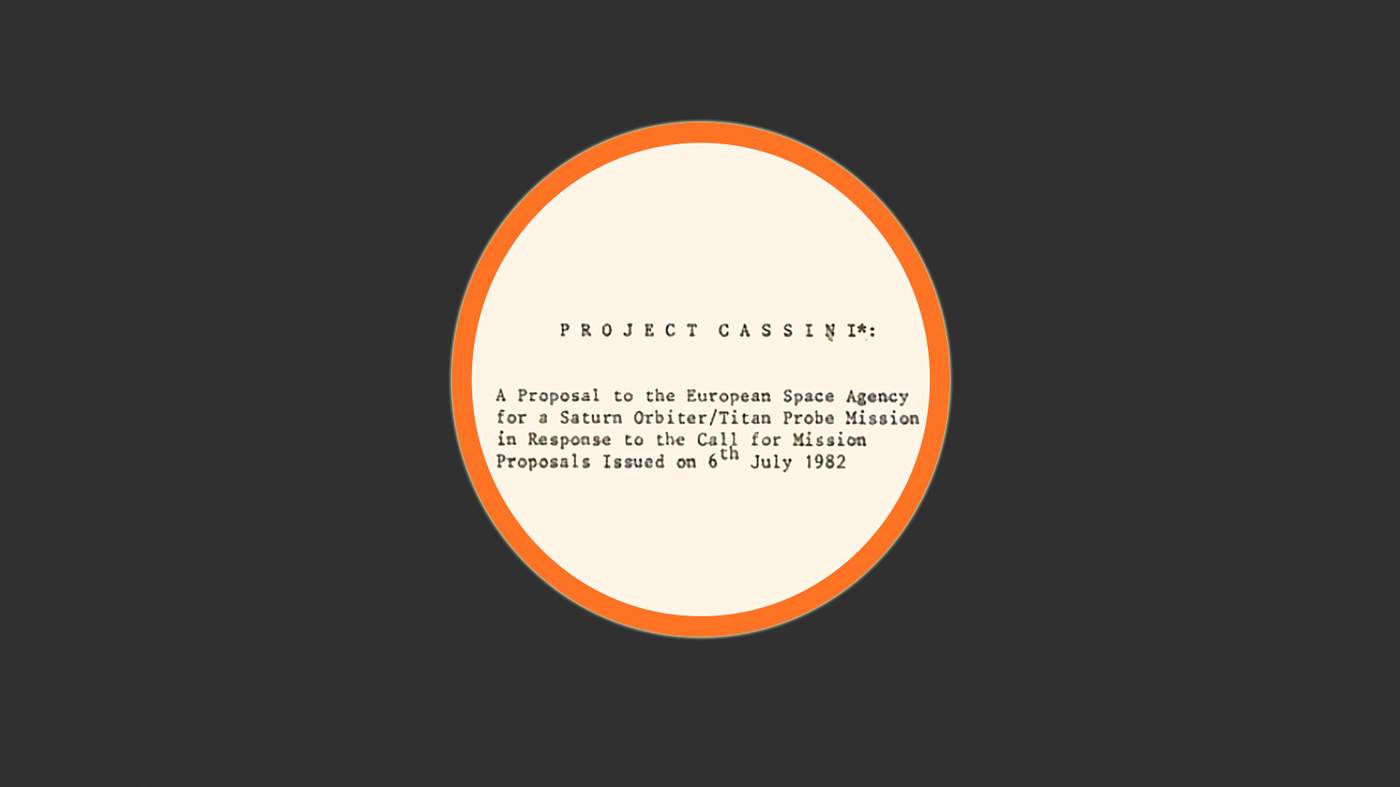

By late 1983, they had decided the prospective mission should be split so that the Americans built an orbiter - named Cassini after a 17th and 18th Century astronomer - and Europe developed a probe to land on Titan.

Giovanni Cassini

(Alamy)

The momentum in the science community eventually led to a detente between Nasa and Esa.

After “Project Cassini” passed a detailed scientific assessment, Nasa and Esa gave the go-ahead to their respective parts of the mission and a unique international collaboration was inked.

But it was a bumpy ride to the launch pad.

Budget cuts in the early 1990s forced the Cassini spacecraft to be re-designed, resulting in the removal of moving parts that would have swivelled instruments to look at their targets.

Instead, the entire spacecraft would have to be turned during observations.

The result, says Cassini project manager Earl Maize, was like going on safari and bolting a camera to the hood of your off-road vehicle.

You would have to turn the whole car to look at the animals, instead of just turning your head and snapping away.

However, the biggest threat to the Cassini-Huygens mission emerged in late 1993. Amid changing political winds, US Congress warned Nasa that its mission could be cancelled.

Esa’s director general Jean-Marie Luton protested in writing to senior US politicians, dangling the prospect of a new freeze in relations.

The ����ý has seen one of the letters, addressed by Luton to then US vice president Al Gore.

Europe, it says, “views any prospect of a unilateral withdrawal from the cooperation on the part of the United States as totally unacceptable. Such an action would call into question the reliability of the US as a partner in any future major scientific and technological cooperation”.

The international dimension to the mission saved Cassini from the disaster of not being launched, says Dr Roger-Maurice Bonnet, science director at Esa from 1983 to 2001.

“This is the advantage of being a European organisation, where 13 member states have 13 ambassadors in the United States, each of them putting pressure on one single government."

Christiaan Huygens

(Alamy)

Dr Bonnet named the Titan lander Huygens on the spur of the moment.

It had been known simply as the “European probe” until quite close to the launch.

But in a meeting, he was challenged to come up with a better name by the Swiss representative to Esa.

“I had just read a few articles on Christiaan Huygens [the Dutch scientist who discovered Titan] and I said: 'Call it Huygens'. It was approved - especially by the Dutch delegation."

By late 1983, they had decided the prospective mission should be split so that the Americans built an orbiter - named Cassini after a 17th and 18th Century astronomer - and Europe developed a probe to land on Titan.

Giovanni Cassini

(Alamy)

The momentum in the science community eventually led to a detente between Nasa and Esa.

After “Project Cassini” passed a detailed scientific assessment, Nasa and Esa gave the go-ahead to their respective parts of the mission and a unique international collaboration was inked.

But it was a bumpy ride to the launch pad.

Budget cuts in the early 1990s forced the Cassini spacecraft to be re-designed, resulting in the removal of moving parts that would have swivelled instruments to look at their targets.

Instead, the entire spacecraft would have to be turned during observations.

The result, says Cassini project manager Earl Maize, was like going on safari and bolting a camera to the hood of your off-road vehicle.

You would have to turn the whole car to look at the animals, instead of just turning your head and snapping away.

However, the biggest threat to the Cassini-Huygens mission emerged in late 1993. Amid changing political winds, US Congress warned Nasa that its mission could be cancelled.

Esa’s director general Jean-Marie Luton protested in writing to senior US politicians, dangling the prospect of a new freeze in relations.

The ����ý has seen one of the letters, addressed by Luton to then vice president Al Gore.

Europe, it says, “views any prospect of a unilateral withdrawal from the cooperation on the part of the United States as totally unacceptable. Such an action would call into question the reliability of the US as a partner in any future major scientific and technological cooperation”.

The international dimension to the mission saved Cassini from the disaster of not being launched, says Dr Roger-Maurice Bonnet, science director at Esa from 1983 to 2001.

“This is the advantage of being a European organisation, where 13 member states have 13 ambassadors in the United States, each of them putting pressure on one single government."

Christiaan Huygens

(Alamy)

Dr Bonnet named the Titan lander Huygens on the spur of the moment.

It had been known simply as the “European probe” until quite close to the launch.

But in a meeting, he was challenged to come up with a better name by the Swiss representative to Esa.

“I had just read a few articles on Christiaan Huygens [the Dutch scientist who discovered Titan] and I said: 'Call it Huygens'. It was approved - especially by the Dutch delegation.”

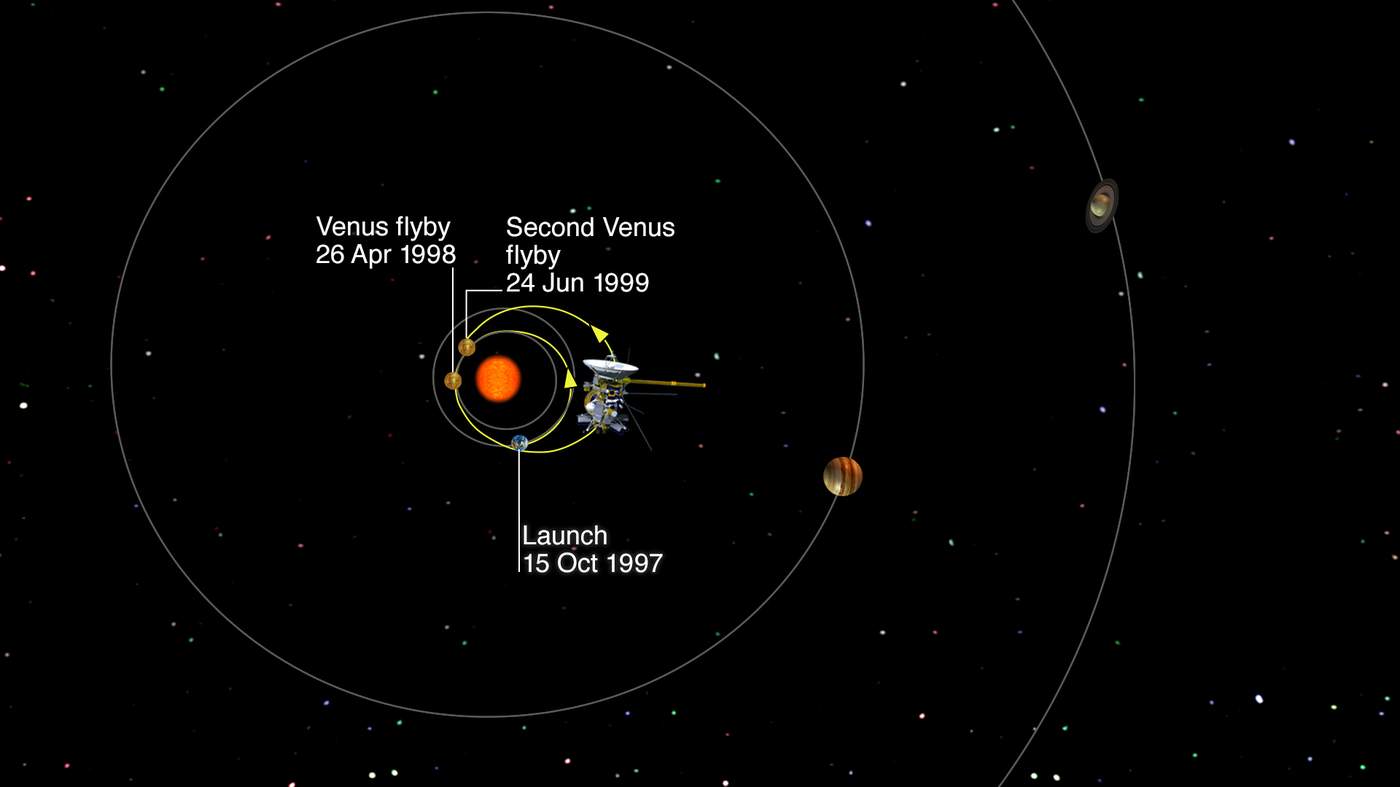

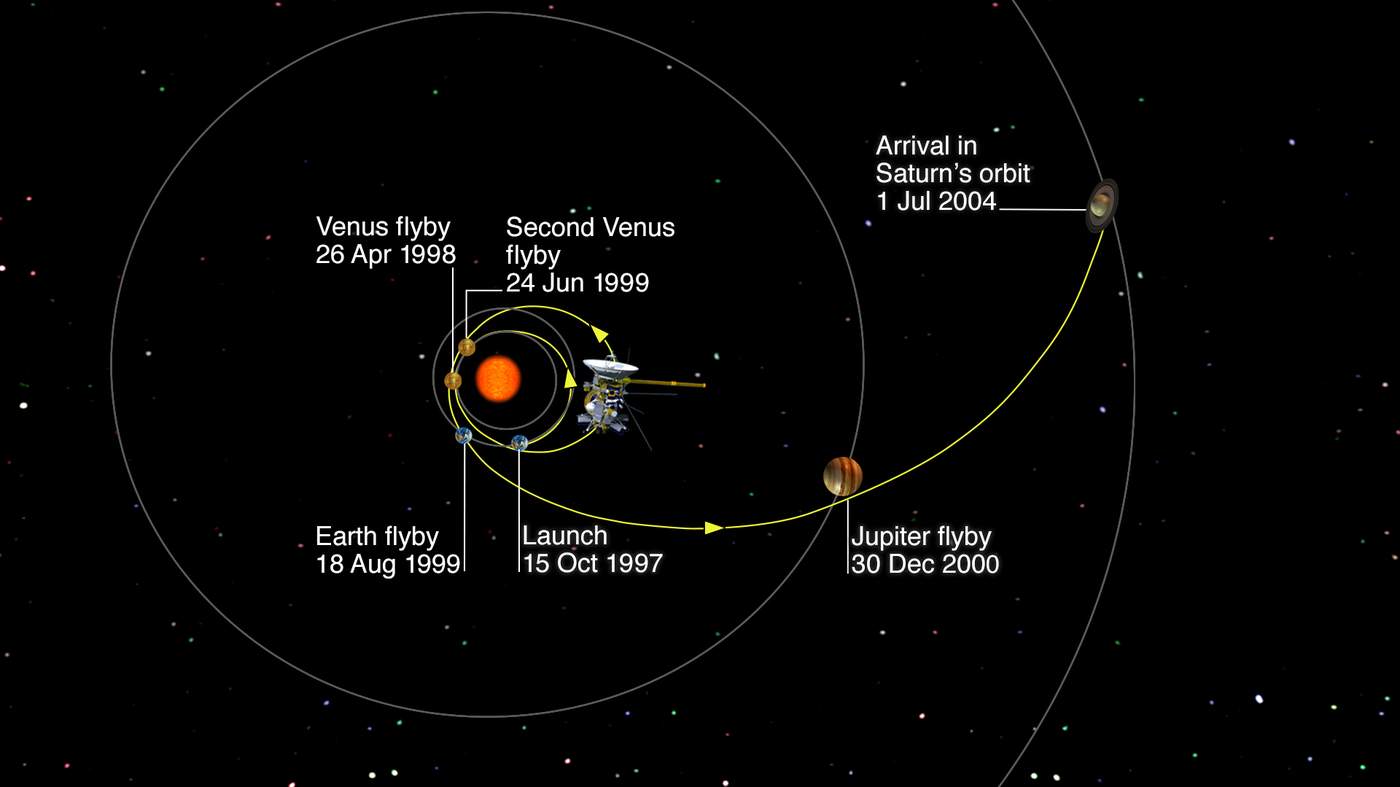

During its seven-year journey, Cassini would carry out several “slingshot” manoeuvres, using the gravity of Venus and Jupiter to alter its path and speed.

This allowed the spacecraft to save propellant and time on its way to Saturn.

Titan IV launch

(Nasa)

On 15 October 1997 - at 04:43 local time - the engines of a Titan IV rocket ignited on the pad at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Florida.

The launcher carried Cassini-Huygens aloft on a brilliant white column of flame.

Titan IV launch

(Nasa)

“It lit up the morning sky,” recalls Jean-Pierre Lebreton, project scientist on the Huygens probe.

“For us, the scientists, a new phase of the mission was starting.”

During its seven-year journey, Cassini would carry out several “slingshot” manoeuvres, using the gravity of Venus and Jupiter to alter its path and speed.

This allowed the spacecraft to save propellant and time on its way to Saturn.

During their construction and assembly, the Cassini orbiter and the Huygens probe had been subjected to rigorous tests.

But in the headlong march to the launch pad there was always the risk that something critical could have slipped the net. It had.

During its descent to Titan, the Huygens probe would use a radio link to send the information it had gathered back to its mothership Cassini, which would be flying in nearby space.

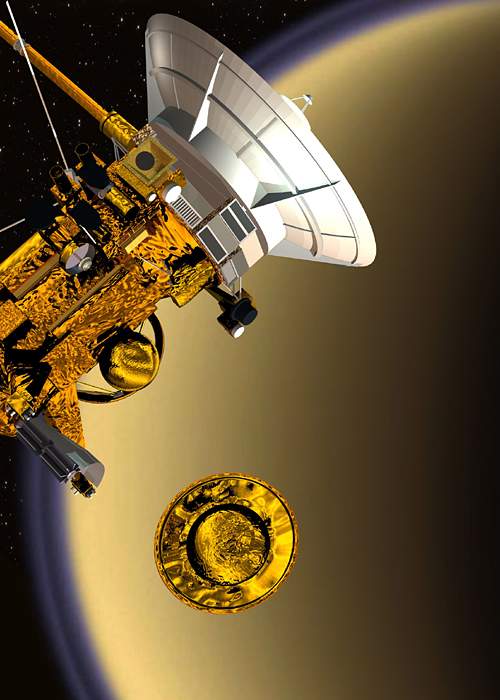

Artist impression of Huygens probe's Titan landing

(Esa)

Once Cassini had received the data, it would be relayed to Earth.

The Huygens landing was a one-shot deal, it had to work perfectly the first time.

Even though Cassini was already en route to Saturn, scientists conceived a plan to test every step of the communications loop ahead of the big day.

Boris Smeds, a senior radio engineer at Esa, was assigned the task of devising and performing the test.

It would need a space communications station on Earth with powerful antennas. Smeds would use one of the antennas to beam a dummy signal to Cassini.

This was designed to mimic the way Huygens would transmit its data to Cassini while it floated down through Titan’s clouds.

An antenna at Goldstone, California

(Nasa)

Smeds secured the use of Nasa’s Goldstone antennas in the Mojave desert, California.

And in February 2000, he was accompanied to a bunker-like room beneath one of Goldstone's 34-metre parabolic antennas and got to work.

He sent out the simulated transmission to Cassini and, using equipment he'd brought over in his luggage, steadily reduced the power to test how resilient the communications system was.

Just like it was supposed to, Cassini beamed the information straight back to Earth.

The data was then sent on to the European Space Agency’s mission control centre in Darmstadt, Germany.

It soon became clear something was wrong.

“I was on the telephone, in contact with Darmstadt. The reports I got from them were very negative, because they didn't receive the data as expected,” Smeds says from his home in Sweden.

Apart from the occasional good data frame, the information sent to Germany was completely garbled.

The problem would soon become clear. Cassini’s receiver hadn’t been built to handle the changes in frequency and wavelength of the signal it would be receiving from Huygens as it descended to Titan.

The train had already left the station, and the problem with the receiver - built by a European contractor - couldn’t be corrected from the ground.

But it was thought there might be a workaround and a “rescue committee” was put together.

Earl Maize of Nasa's Jet Propulsion Laboratory

(Nasa)

“It was a crash effort. I was back and forth across the Atlantic about every month,” says JPL's Earl Maize.

“Once we realised we had some room to move, we mostly just rolled up our sleeves to figure it out.”

If the science data from Huygens couldn’t be decoded, $500m and years of work would disappear down the drain.

The blow to the science community, and Europe in particular, would be devastating.

The problem was affected by the relative speeds of the Cassini spacecraft and the Huygens probe.

So Cassini's trajectory was changed so that it would be much further away and at an oblique angle to Huygens during the landing.

This drastically reduced the relative velocity, preventing the data from getting scrambled.

Artist impression of the Huygens probe separating from Cassini

(Esa)

“Once we found the trajectory option, we could all breathe a sigh of relief,” recalls Maize.

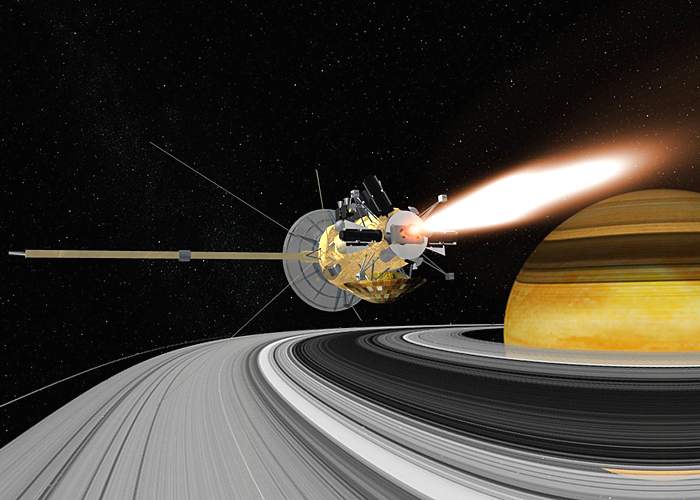

In 2004, after nearly seven years of space travel, Cassini-Huygens had Saturn in its sights.

In order to park itself around Saturn, the spacecraft had to execute a complex manoeuvre called Saturn Orbit Insertion (SOI).

Artist impression of Saturn Orbit Insertion

(Esa)

On 1 July, the spacecraft would cross through a gap in Saturn's rings, moving from the lower side to the upper side as viewed from Earth.

Once through the gap, Cassini would rotate, so that its engine was pointing along the flight path.

The engine would then burn to slow the spacecraft by 600 m/s, allowing it to be captured by Saturn's gravity.

The huge change in velocity required to place Cassini in orbit from its fast approach required a particularly long burn.

“We had to complete a 96-minute engine burn, and we needed to complete at least 92 minutes of that or we risked flying by Saturn - just like the Voyagers,” explains Linda Spilker.

While controllers monitored events at JPL, they were joined in the room by the centre's director Charles Elachi and Nasa's head of science Ed Weiler.

The bosses sat at a table with a jar of lucky peanuts - a tradition at launches and major mission events since the 1950s.

As Cassini travelled along its planned trajectory, the wait was nerve-jangling.

“That was a very tense moment, waiting for that signal while the burn happened when Cassini was behind the planet, so we didn't have a direct signal to the Earth,” Spilker recalls.

“I remember being there with my family - my daughters, my husband, my mum, my sisters, they were all there watching.

“Then Cassini came out [from behind Saturn] and, sure enough, its path was right where it should have been.”

There was jubilation at mission control as team members high-fived and clapped.

Meticulous planning had paid off - with, perhaps, a little help from those peanuts.

Charles Elachi (l) and Ed Weiler (r) - with their peanuts - celebrate Cassini's crucial Saturn Orbit Insertion

(Getty Images)

For Spilker, Saturn's rings had long held a particular fascination, having formed the basis of her PhD thesis.

Cassini was supposed to turn its cameras towards the rings after the engine burn, but the images wouldn't arrive on Earth for several hours.

So she left for home, only to return to JPL early in the morning to see the first photos of the majestic rings being displayed one-by-one.

“I almost felt like I was there, walking through the rings and really seeing them in a way - and at a resolution - that no one had ever seen them before,” she says.

“It was a great day. Cassini was off to a good start.”

With one mission milestone over, the next one was fast approaching: Cassini had to deliver the Huygens probe to Titan.

On Christmas Day 2004, a set of pyrotechnic devices fired, releasing three loaded springs that gently nudged the lander away from Cassini.

As the little probe coasted away from its “mothership”, an anxious three-week wait began.

With battery power switched off, no signal would be heard from the little probe until the day of its descent to Titan.

Jean-Pierre Lebreton recalls: “I said to my colleagues, 'Listen guys, on the 14 January, if the mission is successful, we will not be able to celebrate because we'll be too busy. If it's not successful, if we don't hear from Huygens, we'll be too sad to celebrate'.

“So I convinced myself, and everyone else, that we should celebrate the day before. We had a very nice dinner on the 13 January - with more than 200 people.”

The following morning, Esa's mission control centre on the outskirts of Darmstadt steadily filled with dignitaries, scientists and journalists - I was among them.

The atmosphere was as tense as one would expect.

After powering up in the early hours, Huygens hit the top of Titan's atmosphere (at an altitude of 1,270km) just after 09:00 GMT.

Artist impression of the Huygens probe approaching Titan's atmosphere

(Esa / Getty Images)

As the drag increased, the craft's heatshield was enveloped with a purple glow as surrounding gases were heated to temperatures exceeding those on the surface of the Sun.

In the control room at Darmstadt, team members patiently waited for a transmission showing that Huygens had survived hypersonic entry.

“The first signal that Huygens was alive and descending on the parachute, we got from the Green Bank telescope in West Virginia. This was a very emotional moment I can tell you,” says Dr Lebreton.

David Southwood, Esa’s then director of science, said on the day: “We're doing something today which will last for centuries.”

The onboard science instruments began collecting measurements as Huygens parachuted down through the thick atmosphere.

Part of the Huygens' parachute mechanism

(Getty Images)

After a two-hour-27-minute descent, Huygens finally thumped down on to Titan's frozen surface.

John Zarnecki, chief investigator for Huygens' Surface Science Package (SSP) experiment, memorably described the surface as having the properties of creme brulee (although this was later interpreted as the lander having hit a pebble).

It was nothing short of a triumph, the furthest from Earth humans have ever landed a spacecraft, by some margin. Dr Lebreton remembers:

“I was the project scientist and my job was to ensure that all the scientists responsible for the instruments, would get the data they had been hoping for for 20 years.

“When I saw the data coming back, I said: 'Oh, we have done a good job. We can begin work'.”

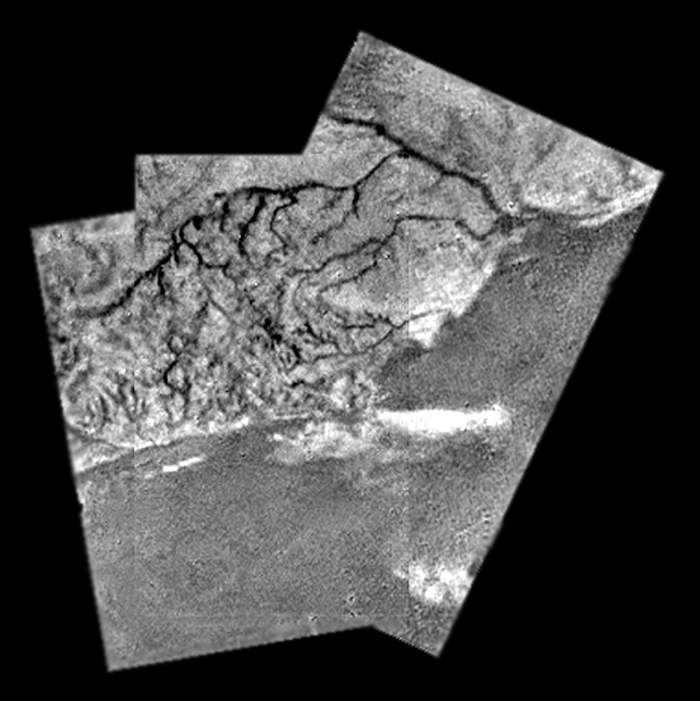

Esa eagerly presented the first pictures from this haze-shrouded world, including a staggering aerial view of Titan's landscape showing what appeared to be drainage channels cut in the ice.

Mosaic image of a river channel and ridge on Titan

(Esa)

Another iconic picture showed Huygens' landing site scattered with rounded pebbles of ice.

Unfortunately, a crucial instruction was missed in a sequence of commands sent up to Cassini.

This simple error caused the loss of one of the two channels used to transmit information from Huygens, leading to gaps in data from some experiments.

Only half the expected number of images were returned and measurements from the probe's Doppler Wind Experiment (DWE) were completely lost.

However, once again, careful planning helped save the day.

“The radio telescope network we set up on Earth recovered the signal that would have been lost otherwise,” says Dr Lebreton.

“On the day we were quite sad, but we quickly realised we had not lost much.”

The Huygens landing remains an amazing achievement, and long in the coming for those scientists like Jean-Pierre Lebreton who had been with the project since the 1980s.

Of the pictures sent back by the camera, Roger Bonnet says: “When I saw the first images of 'rivers' on this moon of Saturn, I said: 'My goodness. We promised that, and we got it'.”

Other onboard experiments profiled the atmosphere, including its temperature, pressure, density and composition, as well as wind strength and direction.

In addition, the probe carried a CD-Rom with drawings, paintings, messages and poems from people around the world.

It also carried music created specially for the disc by two French musicians.

“Huygens is still sitting quietly on Titan's surface waiting for Nasa and Esa to recover the CD,” says Dr Bonnet, although this isn’t likely to happen for decades or even centuries.

One of the two data discs

(Nasa)

This was mirrored by Nasa’s decision to attach a DVD to Cassini carrying the signatures of 616,400 people from 81 countries.

The signatures had been scanned from postcards and letters containing messages of support sent to Nasa.

The effort was described as a “message in a bottle” to Saturn.

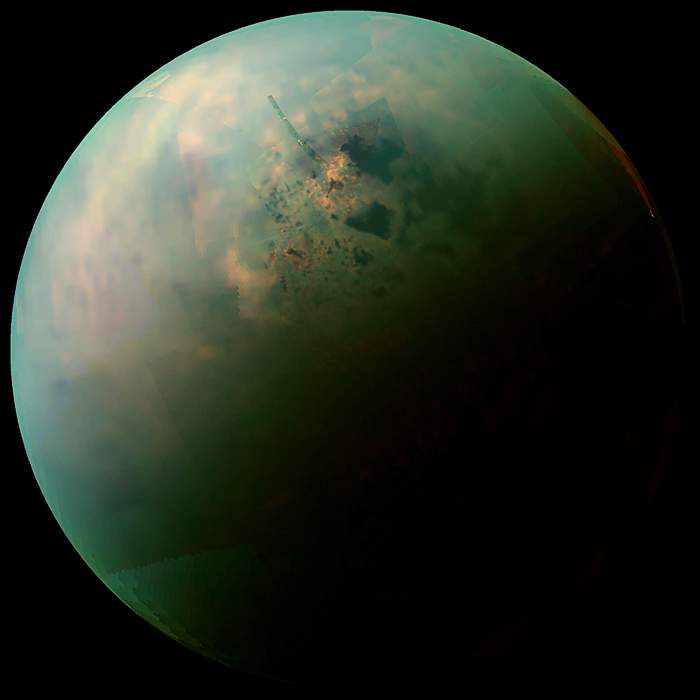

While Huygens provided ground truth, Cassini's radar was able to peer through Titan's clouds from further away.

This revealed a world with its own seasonal cycle, where wind and rain shaped the surface to form river channels, seas, dunes and shorelines.

A false-colour mosaic of Titan made from infrared data - revealing differences in the composition of surface materials around hydrocarbon lakes

(Nasa)

Titan is a mind-bending, through-the-looking-glass version of Earth.

The average temperature of -179C means that mountains are made of ice, sand is made of plastic and liquid methane assumes many of the roles played by water on Earth.

Around Titan's northern pole are three dark methane seas, the largest of which is bigger than Lake Superior in North America. Cassini even resolved gentle (2cm-high) waves and the glint of sunlight reflecting off liquid hydrocarbons.

“The orbiter and the probe really provided a very complementary data-set. They will surely be used for the next 20 years - maybe the next 50,” says Dr Lebreton.

Cassini's looping, elliptical orbit around Saturn was carefully choreographed to enable multiple close flybys of Saturn's many moons.

“Because Saturn's such a rich system, one instrument will want to look one place, another instrument will want to look another,” says Earl Maize.

“It's taken an awful lot of human engineering to integrate all those different scientific objectives into one seamless series of activities.”

During its tour of Saturn, Cassini made a total of 127 close passes of Titan during its mission and 22 of an icy saturnian moon called Enceladus.

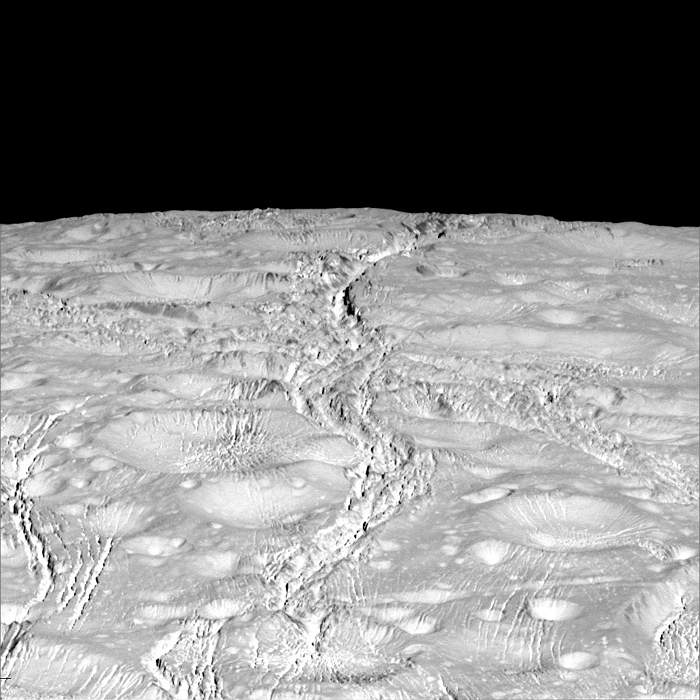

It was undoubtedly Enceladus that served up the biggest surprise of the mission.

Pictures from Voyager 2 revealed a smooth, crater-less surface, hinting at some ongoing geological activity. But Cassini’s instruments detected jets of icy particles gushing out into space from fissures at the south pole known as “tiger stripes”.

What's more, scientists showed that these jets of water were coming from a deep global ocean beneath the outer shell.

“Cassini has been the validation of the theory that you can make liquid water beneath an icy crust even though you are very far from the Sun,” says Nicolas Altobelli, Esa's Cassini project scientist.

Cassini even flew through Enceladus' plumes and used one of its instruments to “taste” what was in it. “It's got organic material in it, and a variety of rocky dust,” says Jim Green.

“That tells us that underneath that ice crust, water is being heated just like the hydrothermal vents heating oceans on Earth.”

Cassini's view of the icy crust on Enceladus

(Nasa)

All of this suggested Enceladus could be one of the best targets in our Solar System to look for extra-terrestrial life.

Indeed, the decision to destroy Cassini is in part because Nasa can't risk the orbiter one day crashing into moons like Enceladus and contaminating them with terrestrial microbes.

As for Saturn itself, Jim Green explains: “It looks a lot like Jupiter in many ways - it’s mostly hydrogen and helium – and there are huge storms that we don’t quite understand the origin of.”

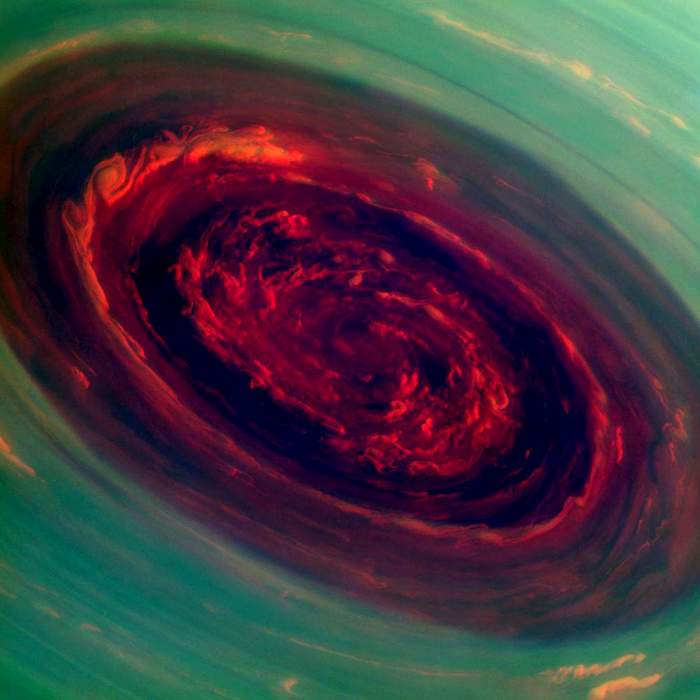

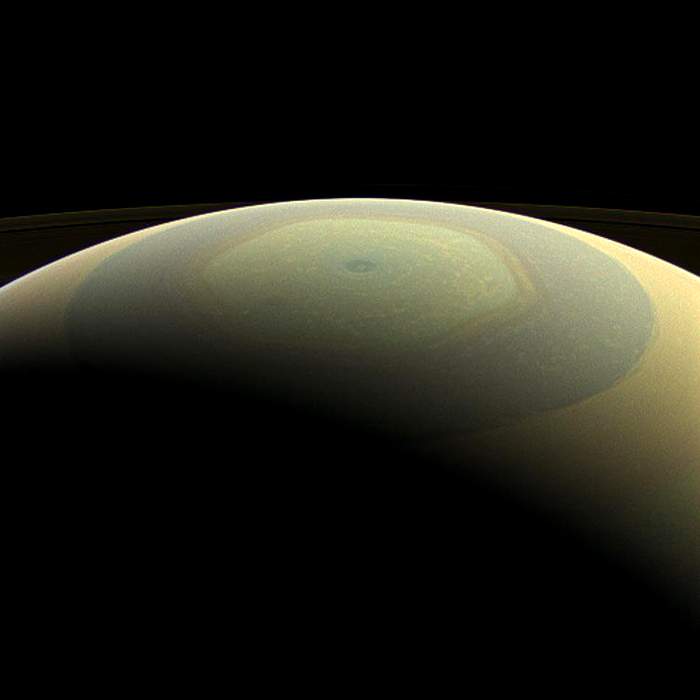

The huge storm at Saturn’s north pole is surrounded by a unique six-sided jet stream known as “the hexagon”.

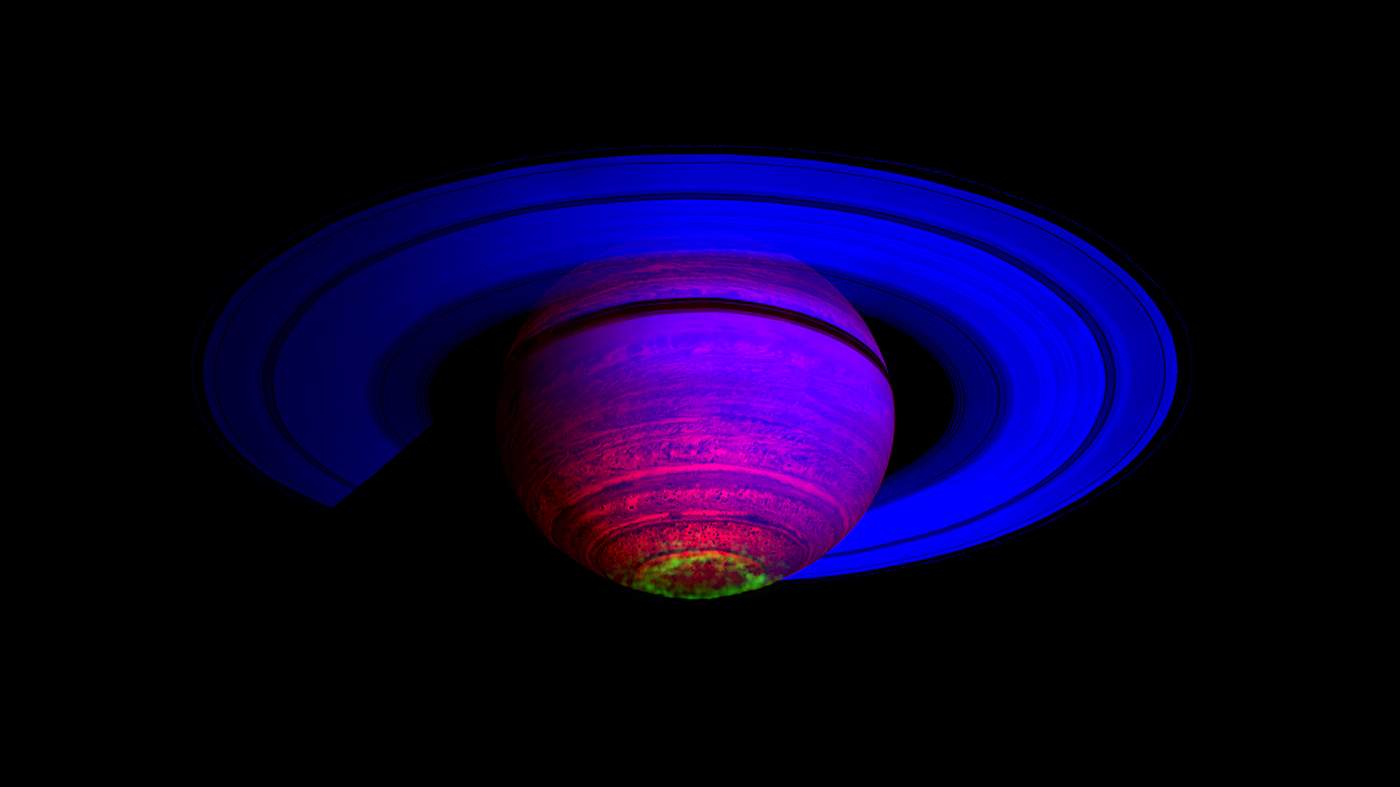

False-colour image of a giant spinning storm at Saturn's north pole - it resembles a deep red rose

(Nasa)

Wider view of Saturn's north pole showing the hexagon-shaped jet stream

(Nasa)

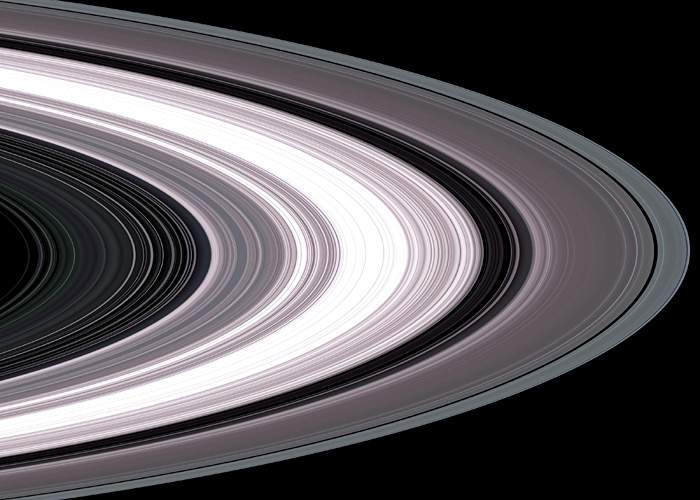

And then there are those majestic pieces of planetary ornamentation - the rings.

How and when the rings formed remains one of the giant planet's biggest mysteries.

Cassini's view of Saturn's spiralling rings

(Nasa)

In August, scientists announced hints that they might be comparatively young, perhaps just 100 million years old.

If that’s the case, it means that we just happen to be living during a special period in Solar System history where Saturn is adorned with these magnificent structures.

The Cassini-Huygens mission has left an indelible mark on human knowledge.

Hundreds of thousands of science observations have led to the publication of nearly 4,000 research papers.

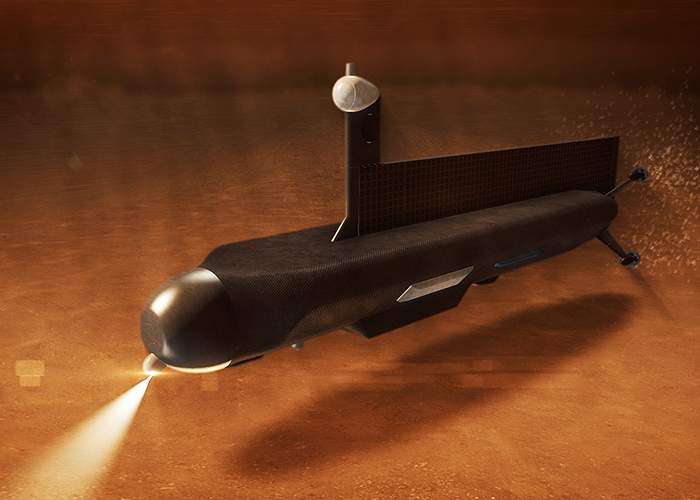

Artist depiction of a submarine on Titan

(Nasa)

And there are numerous ideas for follow-up missions, including a submarine to explore Titan’s methane seas and an orbiter to look for life in Enceladus’ ocean.

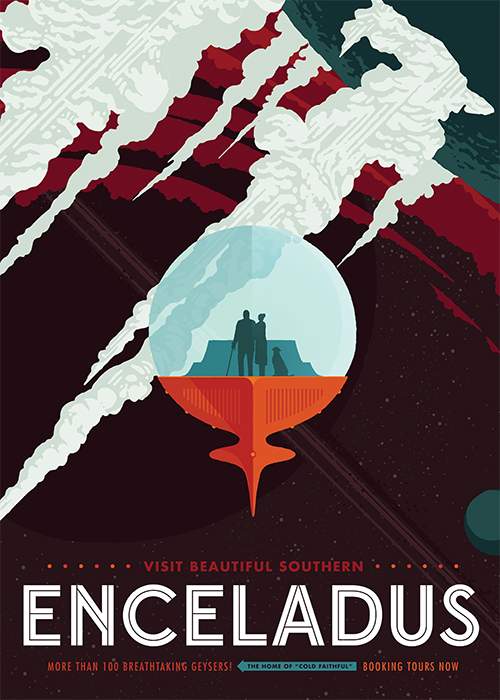

Enceladus “tourism” poster

(Nasa)

But the legacy of Cassini-Huygens is felt in many other ways.

Like the Hubble telescope's images of the distant cosmos, Cassini's iconic pictures of the Saturn system have penetrated popular culture. They can be found on bedroom walls, as computer screen-savers and have influenced big budget Hollywood movies.

Dr Carolyn Porco, who leads Cassini's imaging team, served as science consultant on JJ Abrams' 2009 re-boot of Star Trek.

The film features a major nod to the real-life mission in a scene where the USS Enterprise conceals itself within Titan's dense atmosphere.

As a joint endeavour between Esa, Nasa and Italy's space agency Asi, Cassini-Huygens demonstrated what could be achieved when major space powers pool their resources and expertise.

“We all come from different countries, from different cultures and we have worked spectacularly well together,” says Prof Michele Dougherty, from Imperial College London, chief scientist for the instrument on Cassini’s designed to measure Saturn's magnetic field.

Today, there are no plans for an international space venture on the scale of Cassini-Huygens.

There are challenges. The time taken for Esa to develop missions has increased since the 80s, while Nasa’s development times have stayed the same, making it difficult to synchronise the space agencies’ schedules.

Earl Maize says a repeat of Cassini-Huygens may be a little while coming. All the more reason, perhaps, to savour the mission’s final bow.

On 15 September, Cassini will make a fateful dive into the planet's cloud tops.

It will be destroyed in the atmosphere, becoming a part of the planet it was designed to study.

Artist depiction of the view from Cassini as it falls towards Saturn

(Nasa)

“It's an exciting time, but also a bit of a sad time,” says Linda Spilker.

“What's happening is both an ending and a beginning. It's the end of data collection. But it's the beginning of a legacy where the scientists and engineers will go out and become a part of other missions, taking what they've learned from Cassini with them.”

It looks as if the memory of this mission will be with us for many years to come.