It is just before 15:00 on Saturday in Timbuktu and the intense desert heat has reached its peak.

Five years ago, Islamist occupiers were driven out of the historical town - but violent extremists have never been far away.

A few people are browsing through the silver jewellery and leatherwork at a small Tuareg curio market by the security checkpoint at the airport entrance.

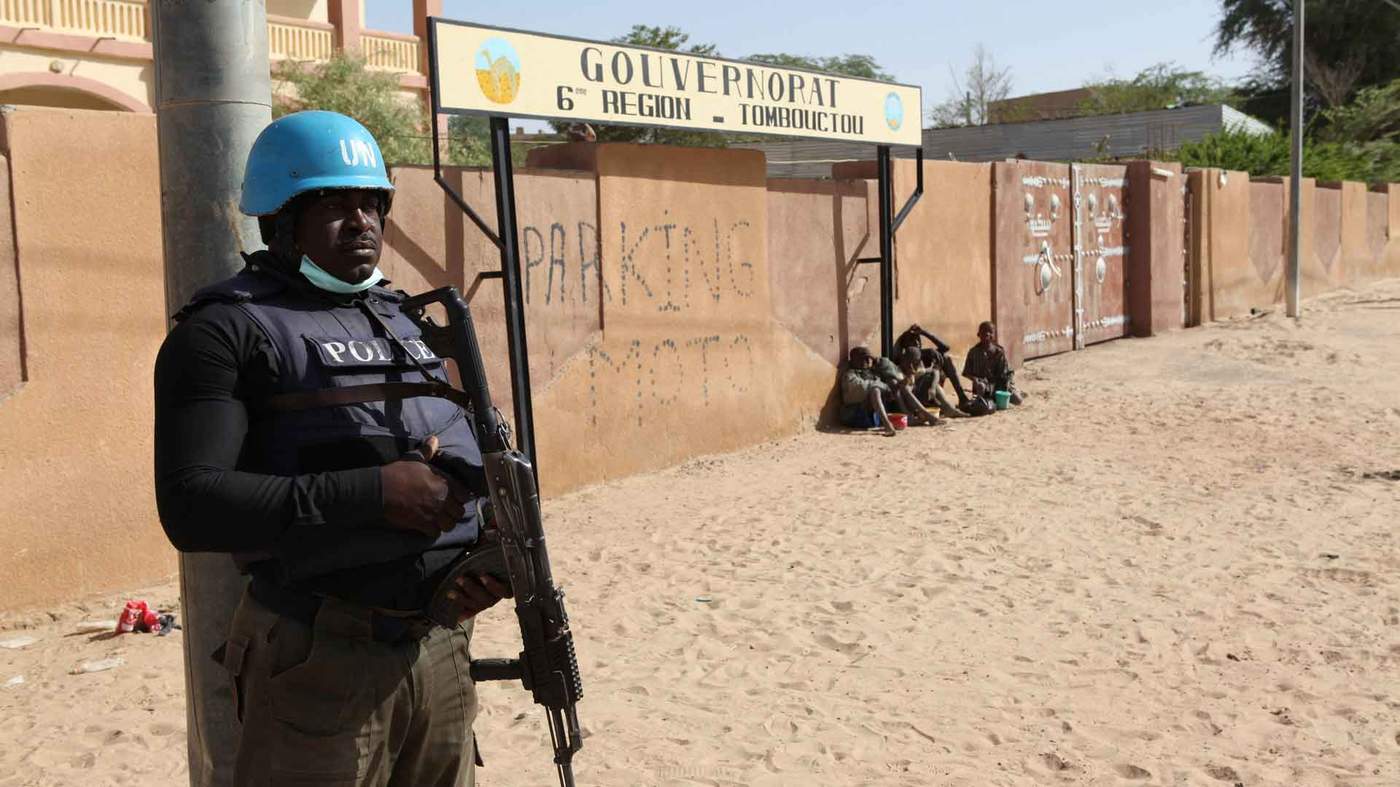

It’s on the outskirts of town and both French troops and UN peacekeepers have set up what they call a “super-camp” there.

At this sleepy time of day, people are working inside their air-conditioned containers and all that can be heard is the low hum of generators.

Then, blaring sirens.

Everyone - whether inside the base or shopping at the market - knows immediately they have less than 30 seconds to reach a bunker.

The early warning sirens mean a mortar or rocket attack is incoming.

One of the shop owners, Amadou (not his real name) knows what to do - he rushes everyone at the market, including four American soldiers, into a small bunker nearby.

Twenty six people are crammed into the small space protected by sandbags - five of them young children.

Then comes the terrifying whistle and crash of mortars.

About a dozen cut through the hazy, sand-soaked sky, exploding in and around the super-camp next to the terminal.

Amadou can see the American soldiers are keen to get to their car and back inside the camp, but he tells them to wait for an all-clear. That saves their lives.

Troops at the first checkpoint are on high alert because of the mortar attack.

But two Malian military vehicles race up, apparently desperate to get inside. Their vehicles aren’t armoured and they are out in the open.

Neither stop to be searched as they swing around the sand-filled bollards at the gate and accelerate through the checkpoint.

From his hiding place in the bunker, Amadou hears the car and then the scream of “Allahu Akbar [God is greatest]”, just before a huge explosion a few metres away.

The first suicide bomber has detonated his explosives-laden vehicle at the first checkpoint, clearing the way for a second bomber to speed through.

The blast rumbles through the camp and the atmosphere inside the bunker changes dramatically.

The children start crying as gunfire erupts around them. But the Islamist fighters don’t know they are there.

Amadou can see people are about to flee the bunker in fear, but the US troops tell everyone to stay down and stay quiet. That saves their lives.

Further up the road, the second bomber accelerates towards French soldiers guarding their section of the camp and explodes right in front of them.

With the outer defences breached, jihadist foot soldiers in Malian military uniforms rush in - at least three of them wearing suicide vests - and so begins an intense battle.

The airport terminal building is almost destroyed.

For three hours, the attackers are repelled. For three hours, 26 people hide in a bunker - terrified they will be found and killed. The four American soldiers are armed only with pistols.

They radio for help but it is only after 18:00, as the Sun is setting, that the gunfire finally stops and a rescue party reaches them.

As everyone in the bunker is rushed inside the super-camp, Amadou sees the dead body of an attacker lying close to what is left of his store.

Timbuktu airport terminal after the attack

But then comes a third car bomb - again at the main gate - perhaps to help the surviving attackers retreat. A fourth unexploded car bomb is found later.

The attack is finally over.

One UN peacekeeper, from Burkino Faso, was killed and seven others were seriously injured. Seven French soldiers and two civilians were also badly hurt.

On the militant side, French forces said 15 had died.

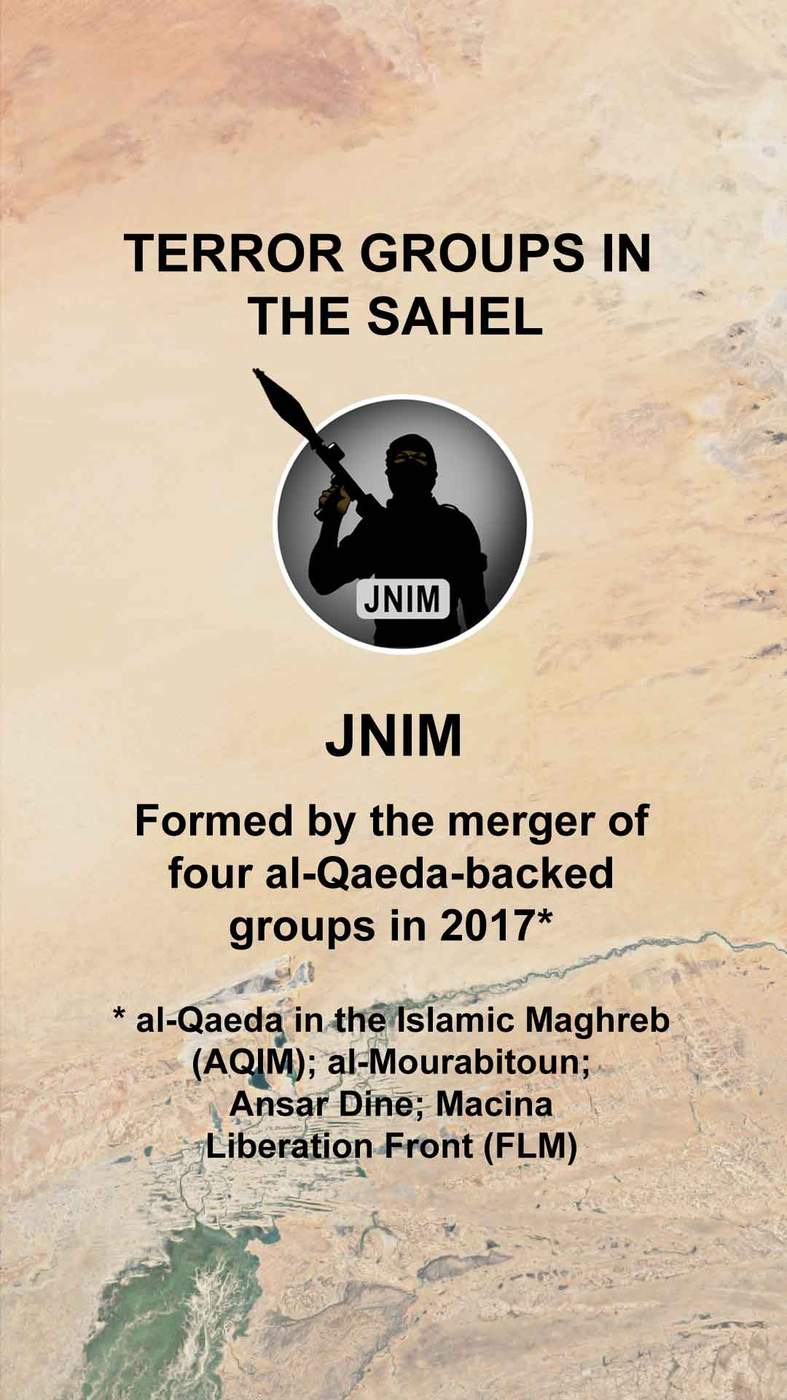

The al-Qaeda-backed group JNIM (Jamaat Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin) claimed responsibility for the most sophisticated attack so far on a military base in Mali.

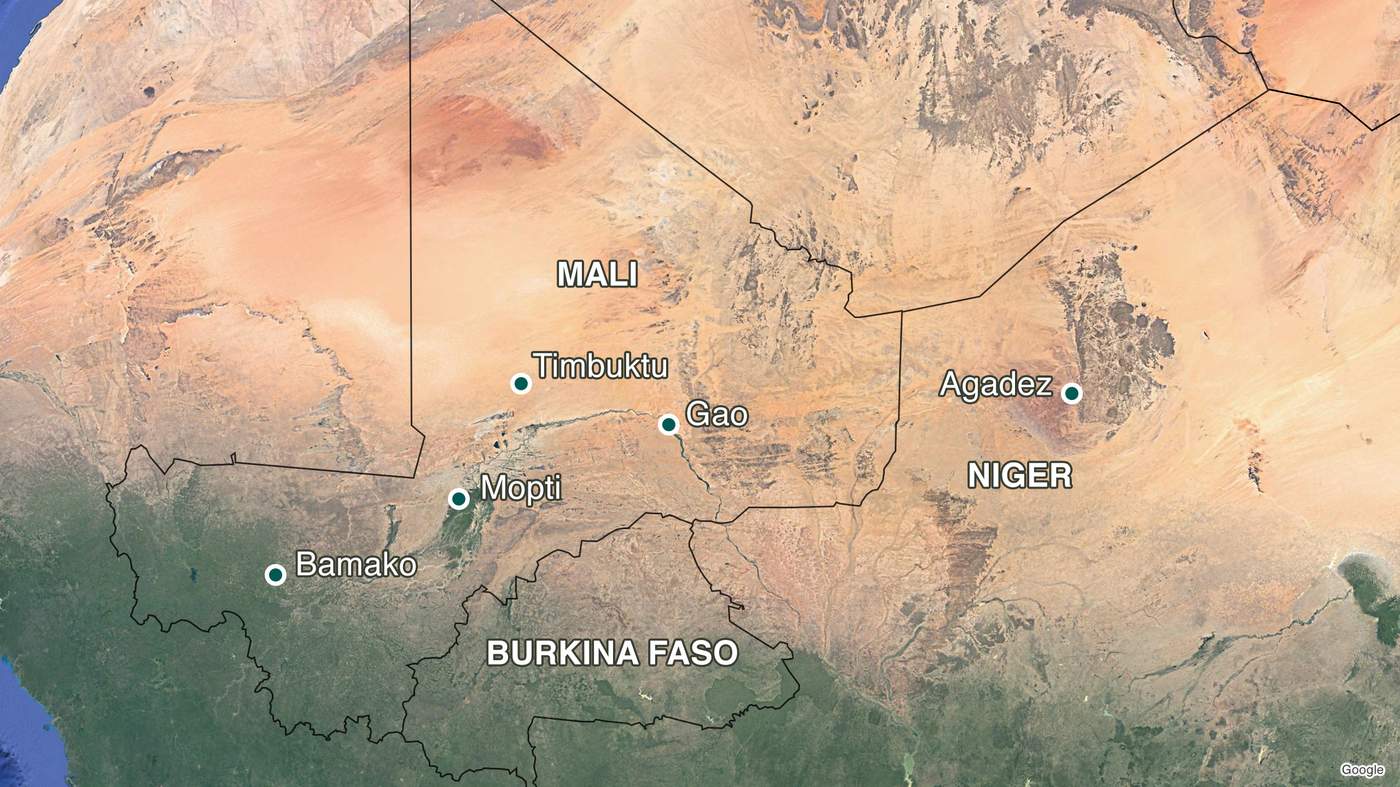

Timbuktu was once at the heart of the Mali Empire. The king is said to have been the richest man ever to have lived - a 14th Century multi-billionaire.

When Mansa Musa I went on the Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca, he brought tens of thousands of courtiers with him, and lavished so many gifts of gold along the way that the price of the precious metal crashed in Cairo.

Mali was an empire built on gold but it also grew rich on trade - in metals, salt and slaves. Traffickers have been making fortunes for centuries moving commodities across the Sahara.

For 250 years, the Mali Empire grew into a centre of learning for science, literature, religion and art.

Scholars from all over the Arab world travelled to the towns that cling to the River Niger as it arcs through the desert - to Timbuktu, Djenne and Gao, where mud mosques were built, and beautiful Islamic scripts were painstakingly written and illustrated.

Djenne’s grand mosque is the largest mud-brick building in the world. Until recently Mali’s rich history attracted hundreds of thousands of tourists every year.

But all that changed in 2012, when the extremists moved in.

Mali’s road to chaos led straight from Libya.

In 2011, the country collapsed as Arab spring protests led to civil war, Western intervention and the death of Col Muammar Gaddafi.

Armed Tuareg mercenaries who had been fighting for Gaddafi headed back home to Mali with renewed purpose, and with weapons.

October 2011: Tuareg rebel fighters in northern Mali

For decades, separatists had been demanding independence for northern Mali. In 2012, Tuareg rebels fighting in a convenient partnership with al-Qaeda-backed Islamists drove the army out and declared an independent state of “Azawad”.

The name of their new state is thought to be an Arabic corruption of the Berber word “azawagh”, meaning “dry river basin”.

As the rebellion spread across northern Mali, disgruntled, underpaid troops staged a military coup in the capital throwing the country into chaos.

The lack of leadership or military response meant the northern uprising was able to spread out of control.

The religious extremists imposed strict sharia law. In Timbuktu and beyond, they smashed shrines built for Sufi mystics, burned manuscripts and destroyed ancient artefacts.

The priceless texts would have all been lost had it not been for the old guardian families who protected what they could.

Tuaregs and Islamists disagreed over the way their new state of Azawad should be run and began to fight each other.

The government asked for foreign military help and the former colonial power France answered the call.

French troops arrived in January 2013 and were joined by African forces. Within a month, they had driven the violent extremists out into the desert and retaken the River Niger towns.

French troops arrive in Mali

The Islamists were down, but not out.

Neighbouring countries and the United Nations came in to support a peace deal between the government and rebellious Tuareg armed groups.

That deal still holds and their guns are broadly silent but good governance has failed to return.

And a far more lethal Islamist threat has returned from the desert.

The extremist groups have gradually been strengthening and uniting and as the dangers have increased, UN troops have taken fewer risks - spending longer in their bases, leaving the desert ungoverned and vulnerable.

Many foreign flags fly over the UN super-camp in the northern Malian town of Gao.

Cambodian troops roll out their bomb-defusing robot, Chinese peacekeepers run the hospital and patrol inside the base, while a carved Pharaonic column overlooks the compound of the Egyptian convoy protection unit.

On the parade ground, the wail of badly tuned bagpipes wafts above the lines of Bangladeshi soldiers, practising for their departure parade just weeks away.

Different countries accept different levels of risk. Many are simply going through the motions - counting down the days, trying to stay alive, and having little real impact in a place where it’s nearly impossible to keep the peace.

Heavily armed Senegalese police in big UN armoured vehicles trundle out of the base and stop at the local police station to escort the commander on his beat through a Gao town bathed in darkness.

UN peacekeepers escort police by night

Their presence is a target. It’s a lot of risk and effort for just a few minutes out meeting people huddled around TV screens watching live European football.

Gao is increasingly becoming a central hub for people trafficking. The Islamist threat is growing and the dangers are increasing.

“All the citizens are scared about the terrorists,” says one man sitting by his motorbike.

“Sometimes they steal the vehicles and kill people so this is not good for us - that is why we are scared.”

A coalition of al-Qaeda groups is vying for influence with the Islamic State group across the vast ungoverned region known as the Sahel, which stretches for thousands of kilometres on the southern edge of the Sahara.

Germany is one of the largest Western contributors to the UN mission. Its helicopters and drones support the supply convoys, which now take weeks rather than days to negotiate their way past roadside bombs in hostile territory.

“That is the main problem we have to cope with and we have to face that violence. We have to protect ourselves, we have to protect the mandate, we have to protect the human system and we have to protect civilians,” says the UN force commander, Maj Gen Jean-Paul Deconinck, a Belgian.

“I need better equipped and better trained contingents. I need more vehicles… to protect my people against the IEDs [improvised explosive devices] and mines and so on and I need to upgrade the training level of my contingents.”

Over the past five years, a memorial wall for fallen peacekeepers has continued to fill up with names. Two more walls are being built.

Hundreds more peacekeepers have been severely injured. The $1bn-a-year (£750m) UN mission to Mali is being carried out in the middle of a raging insurgency. Some believe it’s doing little but creating a target for the jihadists to attack.

While the UN is focused on peacekeeping, France and America are leading counter-terrorism operations intent on search and destroy. Foreign forces are fast militarising the Sahara desert.

On a dusty scrap of desert in northern Niger, the runway at Airbase 201 is gradually taking shape.

A squadron of rollers driven by American troops is readying the long strip of land for a thick layer of asphalt.

First planned as a drone base, it’s going to be far more than that - costing $110m, it’s long enough to land some of America’s biggest military cargo planes and will be home to 800 service personnel.

The US says it’s just temporary and it belongs to Niger. But Airbase 201 is unmistakably American and undoubtedly being built to last.

It’s concrete evidence of how America’s military footprint is spreading across the Sahara.

Just beyond the perimeter fence is Agadez – a former tourist town, which over the past five years has been transformed into the most important hub of the trans-Saharan migrant trade.

Economic migrants have always moved through here, ready to head north across the desert.

But in the chaos of Libya’s collapse in 2011, this trail became a highway.

Criminal gangs moved in and the desert tour guides became human traffickers, carrying lorry-loads of migrants north to the shores of the Mediterranean Sea.

This thriving industry provides both cash and cover for the radical, violent, extremist groups assembling across the Sahara.

The Nigerien town of Agadez

But with corrupt officials taking their cut, there’s little incentive to shut down the trafficking and isolate the Islamists.

“Yes, of course I’m frustrated,” says the head of Nigerien special operations, Col Maj Moussa Salaou Barmou.

“The violent extremist organisations are involved in these illegal migrations. They are making a lot of money out of it.”

Col Maj Barmou is working with the US military, which is piling billions of dollars into the Sahel to counter the gathering Islamist threat in the desert.

There are now at least 7,000 troops and 34 individual US bases or staging posts across Africa - and probably many more secret facilities.

But few people in the US, or in Niger, knew much about the American operations in Africa until four of their soldiers were killed in an ambush at a village called Tongo Tongo last October.

What appears to have been a poorly planned and under-supported mission to target an Islamist leader sparked controversy in the US.

October 2017: the funeral of Sgt La David Johnson, one of three US soldiers killed in an ambush in Niger

Ambushed as they left the village, the convoy of American and Nigerien troops were outgunned and outnumbered, with no armoured cars for protection.

Footage from the soldiers’ helmet cameras was released by their attackers as propaganda - showing the moment they were killed.

Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) claimed responsibility - America’s first introduction to IS in this part of Africa.

The families of the US soldiers were vocal in their criticism of a mission they say was botched, claiming the military had failed their sons.

A US Department of Defense investigation broadly agreed, saying there were “individual, organisational and institutional failures and deficiencies”, but it found that no single failing had led to the loss of life.

As a result, very public questions have been asked about why 800 US servicemen and women are in a country few Americans could point to on a map.

The head of Special Operations Command Africa, Maj Gen Mark Hicks, says the Sahel is vitally important because of the growing strength of the al-Qaeda- and IS-affiliated groups.

“If we don’t take this opportunity to deal with it now, where it’s at a level that’s affordable and sustainable both in blood and treasure, then it may cost much, much more to deal with it at a later time,” he says.

The US recently led the annual Operation Flintlock training exercise, bringing together 12 African and eight Western nations.

2017: Chadian soldiers take part in an Operation Flintlock exercise

For African countries, it was a chance to learn how Western armies worked, and for the visitors it was an opportunity to find “partners” who could help fight foreign terror for them.

The US Special Operations soldiers are training regional forces - sharing their skills with poorly trained and equipped African troops.

“To work by, with and through our African partners and our Western partners as an international coalition of the willing” - that’s the military jargon Maj Gen Hicks repeats. It has echoes of Iraq and Afghanistan.

As rich nations baulk at losing men in a distant desert, these African troops are the boots that will ultimately be on the ground fighting a war on terror for them.

In neighbouring Mali, France has a hands-on strategy through its long-running Operation Barkhane.

A barkhane is a crescent-shaped dune carved by the wind. With 4,500 soldiers based across the Sahel, they are the ones tackling the Islamist threat head on.

For five years they have been carrying out modern counter-terrorism warfare - drone strikes from the air and Special Forces raids on the ground, targeting the leaders and the bomb-makers of the Islamist groups.

“If we were not here, the terrorist groups would thrive in Mali, which would only heighten the global threat, both in the Sahara and in Europe, where we are the most concerned,” says Col Olivier Vidal.

“Our action is effective - it's long term - and it will continue… until the Malian armed forces and the Malian institutions can pick up the fight by themselves, once we have caused the necessary damage to the armed groups.”

France has encouraged five Sahel countries to contribute troops to the 5,000-strong G5 Sahel Joint Force, which will counter terrorism, drug smuggling and human trafficking across the Sahara.

And then there’s the UN’s force, which has a mandate to build and keep the peace.

In Mali, they have almost 14,000 peacekeepers from nearly 60 different countries.

They are now being directly targeted by militants using rockets, roadside bombs or in complex attacks such as the one in Timbuktu.

Blue helmets no longer give the protection - or the sense of neutrality - they used to.

Given the proximity of UN bases to the counter-terrorism units, their heavily armed appearance and a mandate to open fire, the lines are blurring.

That’s why Mali is now the most dangerous UN peacekeeping mission in the world.

The “who’s who” map of most wanted men, and their groups across the Sahel, is a bewildering family tree of alliances and allegiances, old photographs, and long French or English acronyms.

Extremist groups have grown and divided, splintered and reformed, as those backed by al-Qaeda and the Islamic State group battle for power and influence.

Boko Haram, and its offshoot, the Islamic State in West Africa Province, have displaced and terrorised hundreds of thousands of people in north-eastern Nigeria and the bordering countries of Niger, Chad and Cameroon.

Splits in the leadership and a concerted effort by the Nigerian army has eaten into their influence, but the kidnap of schoolchildren and the use of young suicide bombers continues.

But it’s further west - mainly in Mali and the border regions of Burkina Faso and Niger - where attacks are increasing in frequency and sophistication.

Currently, the most powerful group is known as JNIM, which was formed in March 2017 when four al-Qaeda-backed factions merged, overcoming years of splits and divisions over strategy and ideology:

- al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM)

- al-Mourabitoun

- Ansar Dine

- Macina Liberation Front

The coalition’s leaders include former Tuareg rebel leader Iyad Ag Ghaly and veteran jihadist Mokhtar Belmokhtar - whose death has been reported on a number of occasions

JNIM's leaders include the former Tuareg rebel, Iyad Ag Ghaly (left), and jihadist Mokhtar Belmokhtar (right)

JNIM carried out the recent attack on the military base at Timbuktu airport and regularly targets UN and other military convoys with bombs or ambushes.

Its militants have also bombed popular hotels and restaurants in regional capitals in West Africa and attacked civilians in remote villages.

United, the four groups are a much more effective force, each with their own area of influence, sharing intelligence and bomb-making technology.

But there are even more groups to add to this complex picture.

Al-Qaeda and the Islamic State group are unlikely to merge because of ideological differences but there are signs they could collaborate in some fashion here.

With the collapse of the IS “caliphate” in Iraq and Syria, there is a fear some fighters may move through chaotic Libya and on to the Sahel, bringing more sophisticated tactics and bomb technology.

“If just 30 or 40 fighters make it from Syria, it could be a game changer,” says an intelligence operative who doesn’t want to be named.

“The worst case scenario for us is these violent extremist organisations being able to link up,” says Col Maj Barmou.

“You have seen how they have overtaken most of Mali back in 2012, so if nothing is done they would keep on expanding and actually join forces across the continent.”

In some respects it is already too late for Mali.

The country is at the heart of the Islamist threat and attacks have spread from the sparsely populated northern desert into the central and southern parts of the country.

The lack of a government presence is key but a failing economy is allowing the influence of Islamist groups to spread among the young as life grows harder.

You can see the problems in the historical Malian town of Mopti. There, the River Niger is particularly low for this time of year.

The boats that were once packed with tourists are tied up on a beach strewn with plastic rubbish and waste.

Drought is just another blow to the central part of this country that once welcomed tens of thousands of visitors every year wanting to explore its rich past.

The UN says five million people across the Sahel are in need of food aid. More than 1.5 million children are at risk of malnutrition.

Climate change is bringing more extreme weather. There are now few fish and no tourists - the violent extremist groups are close by. Attacks are increasing and young people are being radicalised.

“The government has abandoned this corner of the country. In the last five years, the state has not been present here,” says Djougal Goro, leader of a youth group in Mopti.

“Whoever knows Mopti, knows that Mopti only lives off tourism. The unemployment rate is very, very high here.

“If you’ve nothing else to do but hang around, you will eventually be swayed by negative influences and you will be forced to be radicalised. You will be forced to go to their side. That’s what causes the insecurity here,” he says.

Islamists offer young men hard cash to fight. With no courts to settle land disputes and complex historical, ethnic-based disagreements, their harsh form of justice is becoming the law.

It’s a short, but dangerous drive from the small UN base in Mopti to Kontza - a village about 100km (60 miles) along the River Niger.

Most is tarred road but the last few kilometres is dirt track and UN convoys have been attacked here before.

The vehicles are armoured, the troops heavily armed and an advance party of Senegalese soldiers has been sent ahead a day earlier to secure the route.

Everyone is wearing flak jackets. The troops are on high alert and the UN civilians who have come to meet community leaders have an armed escort through the mud-walled corridors between the family compounds that make up the village.

In one dark room, the men sit cross-legged on the floor as the UN visitors ask about security, development, stabilisation, and women’s rights.

It’s an awkward conversation. The message is that security isn’t good but there’s no further explanation.

“We don’t know who is who,” says Gabriel Branglidor, chief of civil affairs for the UN’s mission in Mali.

He believes the elders are not being completely open in their answers, perhaps because they are fearful of jihadists or their sympathisers.

“We can understand - sometimes you have the perpetrators among those people so they were not allowed to express themselves very freely,” Mr Branglidor says.

The jihadists may well be in the area - not just watching this UN visit from afar, but perhaps among the crowds, watching and listening. The lack of any government presence and only infrequent visits by UN peacekeepers have allowed Islamist groups to wield great influence.

“It is quite obvious that insecurity is in the area. There are some forces here that would prefer Koranic school over secular teaching,” Mr Branglidor says.

The schools here always taught a range of subjects but with growing Islamist influence, the education has been limited to the learning by rote of scripture.

From the gates of the beautiful old Sufi mosque, it’s a short drive to the other side of the village.

Kontza is split along ethnic lines between the Peul and the Dogon. Relations are so bad they have now become completely separate villages.

They are both Muslim but there are big ethnic issues here, which sometimes go back centuries and often involve land disputes between farmers who plant crops and nomadic pastoralists driving their cattle to pasture.

Climate change is driving the Sahara south and reducing the fertile land, while population growth is increasing the competition for dwindling resources.

The Swedish UN force commander for Sector West, Brig Gen Stefan Andersson, is also on the trip - assessing how the civilians work and what he can do to help.

“With the lack of Malian defence and security forces - you have no law and order,” he says. A lack of governance is allowing extremist groups to fill the vacuum.

“They can provide something and they will punish people if they steal motorcycles or cattle. So in many cases the villagers are welcoming them,” Brig Gen Andersson says.

He says the jihadists talk to both sides.

“They are standing in the middle and also provide some kind of security,” he adds.

Towering over a second meeting is a new white and green mosque, which smells of fresh paint.

The UN says Qatari money paid for the building - like Saudi Arabia, here and in other parts of Africa they have a programme that provides new mosques and preachers to teach a very conservative form of Islam.

The children here on this side of the village don’t play football any more. Radios have fallen silent and schools that teach subjects other than religion have closed - the teachers have been intimidated.

It’s happening on a vast scale across the Sahel - from here in Mali to Agadez in Niger. Moderate forms of Islam are giving way to far more conservative Salafist and Wahhabist ways.

Koranic schools are growing stronger, students getting younger, and the teaching is becoming more conservative.

And Africa’s population is growing fast - in Mali and Niger it doubles every 20 years - creating a huge youth bulge.

The lack of education, work and opportunities makes this a prime recruiting ground, creating a new generation of Islamist foot soldiers.

European countries afraid of increasing numbers of migrants, and the Islamists they worry could be hiding among them, are investing heavily in the Sahel to counter the threat.

France has committed thousands of soldiers to Mali and it pushed for the regional G5 force to be formed. That’s still a work in progress.

Three British Chinook helicopters will soon be supporting the French counter-terrorism operation.

Despite a fluid and increasingly dangerous mission, Mali would undoubtedly be worse off if the UN pulled out more than 14,000 people.

And America’s presence in Africa is growing, although its drone strikes and special forces missions are governed by secrecy.

“Right now these threats in Africa are clear, immediate threats to our African partners. But they’re also threats to Western presence in Africa and they aspire to be threats to the West directly,” says Maj Gen Hicks.

He worries Islamic State fighters fleeing Syria and Iraq will come to the Sahel and “that could be devastating to the security situation across North Africa”.

It’s an obvious place to come, where weak governance, corruption, ethnic division, drought, poverty, unemployment, population growth and climate change all combine to give Islamists a unique opportunity.

It’s the new, desert front line in the global war on terror.

Authors: Firle Davies & Alastair Leithead

Stills photographs: Firle Davies

Drone footage: Olivier Salgado

Graphics: Tom Housden & Nick Davey

Additional photographs:

Getty Images

Reuters

EPA

Alamy

Google Earth

All images subject to copyright

Online production: Ben Milne

Editor: Finlo Rohrer

Published: 21 June 2018