LHC finds 'interesting effects'

- Published

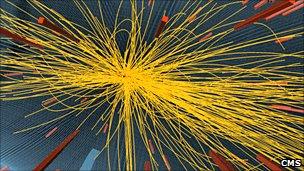

Scientists have tracked particle paths in billions of collisions at the LHC

Scientists at the Large Hadron Collider say they are getting some fascinating early results as they get set to probe new areas of physics.

The giant machine on the Franco-Swiss border is studying the fundamental nature of matter by smashing together proton particles at near light-speed.

Its CMS detector is reported to have seen "new and interesting effects".

These effects concern the particular paths taken by the debris particles as they move away from the impacts.

These angular correlations emerged in the statistical study of particle movements in billions of collisions.

"In some sense, it's like the particles talk to each other and they decide which way to go," explained CMS Spokesperson Guido Tonelli.

"There should be a dynamic mechanism there somehow giving them a preferred direction, which is not down to the trivial explanation of momentum and energy conservation. It is something which is so far not fully understood," he told ҙуПуҙ«ГҪ News.

Mr Tonelli said the effects were small and had prompted much debate; although he said they probably did not indicate any new physics.

"We claim only that we have seen something unusual and we want the scientific community to criticise us, to understand if we did things correctly or if we did something wrong," he added.

The results are said to be interesting because they mirror similar observations at the US Brookhaven National Laboratory, which has been employing a lower energy machine but using more massive atomic nuclei as the impactors.

Such investigations are part of the quest to understand the hot dense state in which matter is thought to have existed just fractions of a second after the Big Bang.

Researchers want to see evidence of this state, known as a quark-gluon plasma, so they can explain how it transitioned into the ordinary nuclear material that makes up the Universe today.

The LHC will begin to probe this domain itself in November when it starts colliding the nuclei of lead atoms.

The ВЈ6bn ($10bn) machine is operated by Cern (the European Organization for Nuclear Research), based near Geneva.

Opened in 2008, it already works at energies that exceed those of previous colliders and is still some way short of its maximum design performance.

Currently, much of what the collider is doing is proofing its own operation by re-measuring known physics.

This will give researchers a baseline from which to understand better the results thrown up by future, more ambitious experiments.

- Published23 July 2010

- Published22 July 2010