Comet's water 'like that of Earth's oceans'

- Published

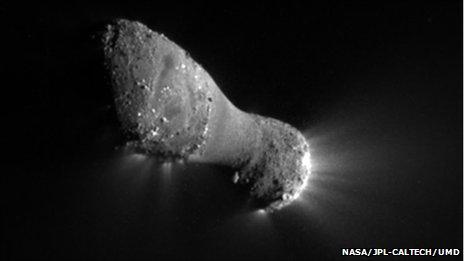

Comet Hartley 2 was also the subject of the Deep Impact probe study

Comet Hartley 2 contains water more like that found on Earth than all the comets we know about, researchers say.

A study using the Herschel space telescope aimed to measure the fraction of deuterium, a rare type of hydrogen, present in the comet's water.

Like our oceans, it had half the amount of deuterium seen from other comets.

The result, , hints at the idea that much of the Earth's water could have initially come from cometary impacts.

Just a few million years after its formation, the early Earth was rocky and dry; most likely, something brought the water that covers most of the planet today.

Water has something of a molecular fingerprint in the amount of deuterium it contains, and only about half a dozen comets have been measured in this way - and all of them have exhibited a deuterium fraction twice as high as the oceans.

Asteroids, by contrast, give rise to the meteors and meteorites that arrive on Earth, making their deuterium fraction more well-established.

Meteoritic material has roughly the same proportion of deuterium that the Earth's oceans contain, and so the assumption has been that if water arrived from elsewhere, it came from asteroids.

Clouded measure

Until now, all of the comets that have been measured have been so-called Oort Cloud objects, believed to have been formed early in the Solar System's history in the region of the giant planets Neptune and Uranus and kicked out to a great distance as they bumped into the planets and each other.

Comet Hartley 2 is the first "Kuiper Belt" object to undergo the deuterium analysis. Kuiper belt objects formed not far outside our Solar System, and comets that originate there have much shorter orbits than those from the Oort Cloud.

Comets carry much more water than asteroids, but it may or may not be like the water found on Earth

An international team using the Herschel telescope to peer at the comet, they found it had a deuterium fraction much closer to that of our oceans.

Report co-author Ted Bergin of the University of Michigan said that opened up the possibility that comets at least contributed to our water supply.

"The reservoir of Earth ocean-like material is much larger than we thought, and it encompasses cometary material, which we hadn't recognised," he told 大象传媒 News.

"We have to think really hard and try to get a better understanding of what is going in our Solar System, and whether you can really rule out comets as the source of Earth's water."

They might not be ruled out, but they are not the definitive answer either; much of what we believe happened in the early Solar System is based on computer models.

James Greenwood of Wesleyan University in the US said such models may need adjusting in light of the new evidence - and that more such studies are needed to assess whether many Kuiper Belt objects are like Hartley 2.

"If the short-period comets are all like this one comet, then this could be a significant source of our early water," he told 大象传媒 News.

"It opens up a new can of worms for us."

Alessandro Morbidelli of the Observatory of Cote d'Azur argues that the result shows that the distinction between the potential water sources may need to be called into question.

"In the past, scientists thought that these asteroids and comets were completely different classes of bodies. Now, several new results show that primitive asteroids and comets are brothers and sisters," he told 大象传媒 News.

"This new view changes at least the semantics of the question on the origin of the Earth's water. The question becomes more technical: 'from which region of the disc and by which dynamical mechanism came the (objects) that delivered the water to the Earth?'"

Herschel has some time left to address the question, but what all the researchers agree is that the Atacama Large Millimeter Array of telescopes in Chile - which has just shown off its first results - will soon be able to resolve these questions with never-before-seen sensitivity.

- Published4 November 2010

- Published16 February 2011