Dwarf planet Pluto's dark and light terrains

- Published

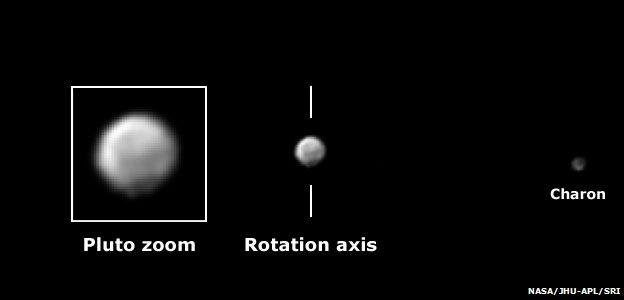

Pluto seen by LORRI on 28 May at a distance of 56 million km

Pluto continues to get bigger in the viewfinder of New Horizons' cameras.

The Nasa spacecraft is now less than 40 million km from making its historic flyby of the dwarf planet on 14 July.

The latest pictures, acquired by the probe's Long Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI), show distinct surface regions - some bright, some dark.

Quite what they represent is anyone's guess just at the moment, but as New Horizons bears down on Pluto, these features will only get clearer.

Scientists have to do quite a bit of processing to produce these views, and it is always possible that they have introduced some artefacts. But the impression that the body has some really quite diverse terrain seems quite solid now.

"Even though the latest images were made from more than 30 million miles away, they show an increasingly complex surface with clear evidence of discrete equatorial bright and dark regions - some that may also have variations in brightness," said New Horizons principal investigator Alan Stern, of the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado.

"We can also see that every face of Pluto is different and that Pluto's northern hemisphere displays substantial dark terrains, though both Pluto's darkest and its brightest known terrain units are just south of, or on, its equator. Why this is so is an emerging puzzle."

New Horizons is now about 4.7 billion km (2.9 billion miles) from Earth and just 39 million km (24 million miles) from Pluto itself.

When it arrives at the dwarf, - far too fast to go into orbit.

Instead, it will execute an automated, pre-planned reconnaissance, grabbing as many pictures and other data as it can as it barrels past the 3,200km-wide planet and its five known moons - Charon, Styx, Nix, Kerberos and Hydra.

Last week, researchers working on the Hubble space telescope revealed how the smaller satellites behaved in a chaotic manner as they circled the more tightly bound Pluto and Charon.

Hubble showed the little moons to be wobbling end over end as they moved through the bigger pair's lumpy gravity field.

LORRI sees the different faces of Pluto rotate into view over six days

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter:

- Published4 June 2015

- Published13 May 2015

- Published30 April 2015

- Published15 April 2015

- Published5 February 2015

- Published25 January 2015