Signal may be from first 'exomoon'

- Published

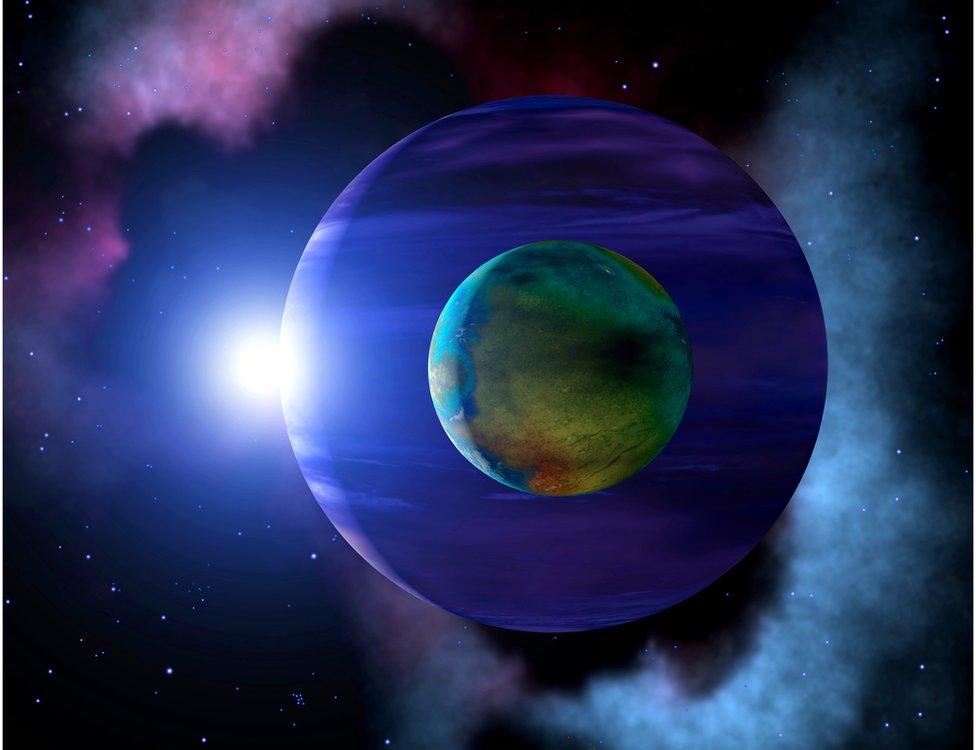

Artist's impression: Where there are exoplanets, there are probably exomoons

A team of astronomers has potentially discovered the first known moon beyond the Solar System.

If confirmed, the "exomoon" is likely to be about the size and mass of Neptune, and circles a planet the size of Jupiter but with 10 times the mass.

The signal was detected by Nasa's Kepler Space Telescope; astronomers now plan to carry out follow-up observations with Hubble in October.

A paper about the candidate moon is .

To date, astronomers have discovered more than 3,000 exoplanets - worlds orbiting stars other than the Sun.

A hunt for exomoons - objects in orbit around those distant planets - has proceeded in parallel. But so far, these extrasolar satellites have lingered at the limits of detection with current techniques.

Dr David Kipping, assistant professor of astronomy at Columbia University in New York, says he has spent "most of his adult life" looking for exomoons.

For the time being, however, he urged caution, saying: "We would merely describe it at this point as something consistent with a moon, but, who knows, it could be something else."

The Kepler telescope hunts for planets by looking for tiny dips in the brightness of a star when a planet crosses in front - known as a transit. To search for exomoons, researchers are looking for a dimming of starlight before and after the planet causes its dip in light.

The promising signal was observed during three transits - fewer than the astronomers would like to have in order to confidently announce a discovery.

The researchers will conduct follow-up observations with Hubble in October

The work by Dr Kipping, his Columbia colleague Alex Teachey and citizen scientist Allan R Schmitt, assigns a confidence level of four sigma to the signal from the distant planetary system. The confidence level describes how unlikely it is that an experimental result is simply down to chance. If you express it in terms of tossing a coin, it's equivalent to tossing 15 heads in row.

But Dr Kipping said this is not the best way to gauge the potential detection.

He told “óĻó“«Ć½ News: "We're excited about it... statistically, formally, it's a very high probability. But do we really trust the statistics? That's something unquantifiable. Until we get the measurements from Hubble, it may as well be 50-50 in my mind."

The candidate moon is known as Kepler-1625b I and is observed around a star that lies some 4,000 light-years from Earth. On account of its large size, team members have dubbed it a "Nept-moon".

A current theory of planetary formation suggests such an object is unlikely to have formed in place with its Jupiter-mass planet, but would instead be an object captured by the gravity of the planet later on in the evolution of this planetary system.

The researchers could find no predictions of a Neptune-sized moon in the literature, but Dr Kipping notes that nothing in physics prevents one.

A handful of possible candidates have come to light in the past, but none as yet has been confirmed.

"I'd say it's the best [candidate] we've had," Dr Kipping told me.

"Almost every time we hit a candidate, and it passes our tests, we invent more tests until it finally dies - until it fails one of the tests... in this case we've applied everything we've ever done and it's passed all of those tests. On the other hand, we only have three events."

The work by Dr Kipping and colleagues forms part of the collaboration.

Follow Paul