'I run for the family I'm not allowed to see'

- Published

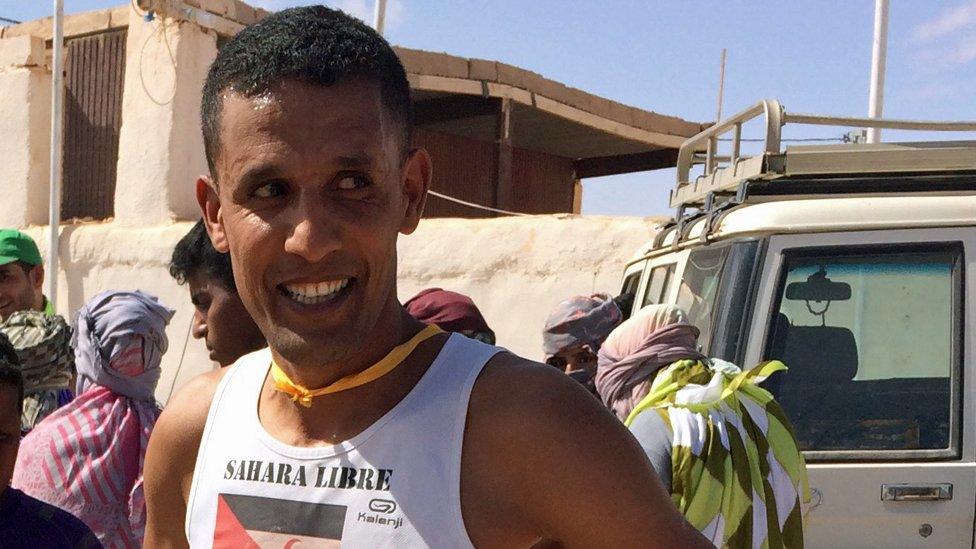

There is one event that long-distance runner Salah Ameidan takes part in every year - the gruelling Sahara Marathon in south-west Algeria. It's not only the thrill of the competition that attracts him, though - this is also the closest he can get to his family, who live behind a wall in the desert, in territory governed by Morocco.

We're deep in the desert in south-west Algeria looking out at parched, cracked flatlands. With minutes to go before the horn blows, I join Salah Ameidan on his gentle warm-up as he prepares his mind and his lithe limbs for the tough terrain ahead.

Around us, hundreds of athletes are gathering at the starting line dressed in neon yellow and orange Lycra, using the pointy edges of their neck scarves to rub sand out of their eyes.

The conditions for today's run are likely to be treacherous: burning breeze, wandering camels and shifting sand dunes.

But Ameidan's not concerned about that - his mind is elsewhere.

He's reflecting on previous long-distance runs in his homeland, Western Sahara, when his father was still there to cheer him on.

"My father passed away a year and a half ago but I wasn't allowed to go to his funeral," he says.

He hasn't seen his family since 2004, when, while racing in France, he raised the flag of the Saharawi people - the indigenous population of Western Sahara - and fled into exile in France rather than return to likely imprisonment in Morocco.

Women provide water, dates and oranges at a drinking station along the route

Ameidan was 12 years old when he was recruited to run for the national Moroccan athletics team. Within 10 years he had become one of the world's top long-distance runners - the Moroccan national champion and the Arab World Champion on two occasions.

But a race in 2000 altered the course of his life.

"I won, but I was forbidden from having the prize," he says. "At that point, I began to think about how to make my own way and to get myself out of this system."

Find out more

Listen to Western Sahara's Champion Athlete on Assignment, on the 大象传媒 World Service

Click here for transmission times or to catch up online

It was this that led ultimately to his act of protest in France, four years later.

On entering the stadium at the end of a 10km race, Ameidan took the Saharawi flag - illegal in Morocco - from a friend in the crowd, and raised it victoriously while crossing the finish line.

"I realised there had been something missing inside of me. I felt a sense of freedom holding the Saharawi flag - and, for the first time, a sense of responsibility," he tells me.

From this moment on, he hasn't been able to safely visit them, and his family can't go to France for fear that they wouldn't be allowed to return home.

"My mother and my sister are still in the occupied territories but I am banned from visiting them," he says.

Eleven members of his wider family have been arrested and interrogated because of his actions.

"I put myself and my family at serious risk."

A lone Saharawi competitor runs past the refugee camps

The closest Ameidan can get to his family is here on the Algerian border, 500km away from his home city of Laayoune in what Saharawis call the "occupied territories" of Western Sahara, close to the Atlantic coast.

Morocco has claimed those areas since 1975, when its troops moved in from the north, sparking a bitter, bloody war with the indigenous Saharawi people.

It was to be a temporary move but, a generation later, the territories remain divided by a heavily landmined wall snaking 2,700km through the desert. Land to the east of the wall is governed by the Polisario, the Saharawi independence movement. The Berm of Shame, as it's known to local Saharawis, continues to separate thousands of families like Ameidan's.

When the conflict broke out, those who could fled across the desert to neighbouring Algeria, seeking sanctuary. There, in Tindouf province, they set up six refugee camps, now home to tens of thousands of people. The Sahara Marathon is run through those camps - and some of those who live there are taking part in the race, which is another reason it's an unmissable event for Ameidan.

"I'm so happy to be back among my people," he shouts over to me while posing for selfies with enthusiastic fans. "Every year I get just one month's break and I choose to come here. That shows how important it is for me to participate in this race."

Most of the rest of the year he lives in France, where he works as a running coach.

But grateful as he is to have been offered sanctuary by the French authorities, he has declined citizenship.

"You only have one homeland," he says.

"I made my decision to be pure Saharawi - it's not good to make a lot of contradictions."

Salah Ameidan holding the Saharawi flag after the race

Since the fateful 2004 race, running has become more than a sport for Ameidan - it's a platform to highlight the plight of the Saharawi people.

"Running is a weapon that I can use to amplify my people's voices and it's a peaceful one," he says.

"You taste freedom when you run but it's an incomplete and unfinished freedom. As long as my land is occupied, I can't fully enjoy my freedom."

Saharawi women ululate and fly the flag

Being banned from Morocco, and separated from his family, is the price he has to pay for his political convictions. "And I will happily pay it," he says.

But, at least in the elation of a successful race - he came second in the 10km event, with a time of 36:03 - he is far from downhearted.

I battle through the hordes of fans at the finish line to speak to him. He mops beads of sweat from his brow, and gestures to the ululating crowd.

"We are so determined to reach our goal of independence," he says, "I consider this stage as a bridge before we go back to our country. Without hope, there is no life..."

Listen to Western Sahara's Champion Athlete on Assignment on 大象传媒 World Service

Nicola Kelly is on Twitter

You may also like:

When former Olympic pentathlete Mauro Prosperi took part in the 1994 Marathon des Sables, he got caught in a sandstorm and was lost in the desert for 10 days.

Join the conversation - find us on , , and .