Tech Tent: Was it a Facebook election?

- Published

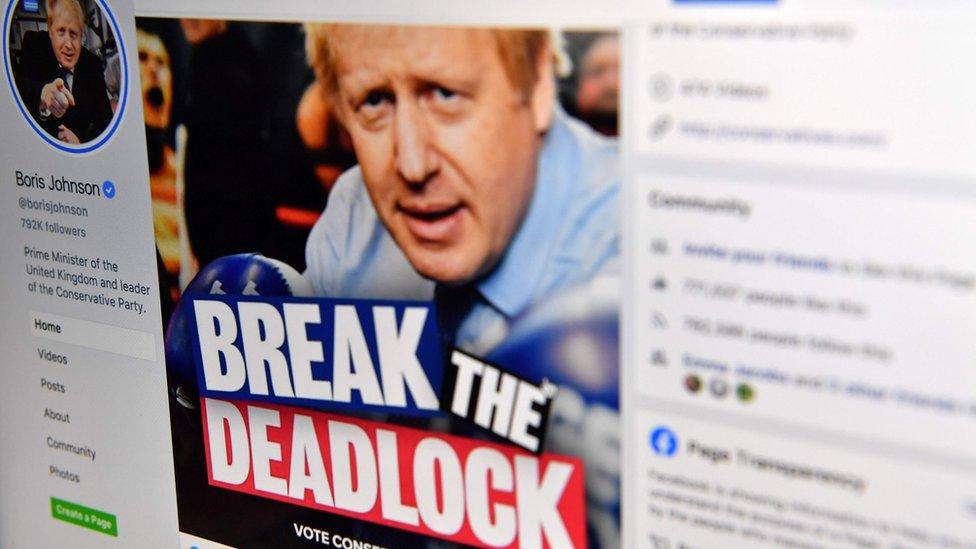

The Conservatives placed thousands of ads on Facebook - but so did their rivals

It was an election in which tens of thousands of targeted adverts from all sorts of organisations reached voters via social media.

On this week's Tech Tent podcast, we explore the role played by Facebook and other platforms in the UK election, and ask whether there are lessons to be learned for global regulators.

Lisa-Maria Neudert of the Oxford Internet Institute has been researching online propaganda and media manipulation.

So, do targeted adverts work? "Yes and no," she tells us.

Do voters simply see an ad and then vote for that party?

"That is definitely something that is not happening. But we do know that ads really help with visibility, setting the agenda, bringing a particular topic more into the conversation," she says.

This year, Facebook - undoubtedly the biggest player in this kind of targeted advertising - has introduced a measure of transparency into how the whole business works. Adverts have to say who paid for them, and are listed in an online archive.

It may surprise you to know the Ad Library has details on how much the parties spent. Labour and the Liberal Democrats, the big losers in this election, outspent the victorious Conservatives by quite a margin.

But the election also saw lots of obscure non-party groups, many formed just before the campaign, buying adverts on Facebook.

In the shadows

The organisation Who Targets Me, which collects examples of targeted ads via a browser extension, looked at the ads people saw on polling day.

They found that adverts from seven non-party organisations had been seen more than ads from the Conservatives, Labour and the Liberal Democrats.

Those ads were from three groups encouraging those wanting to remain in the European Union to vote tactically, and four groups campaigning against Jeremy Corbyn's Labour Party.

Now it is clear that the tactical voting ads were a waste of money, and it is hard to know whether voters were really swayed by the anti-Corbyn messages.

But the organisation still thinks there is cause for concern.

"We're deeply worried about the emergence of new, opaque and seemingly disposable Facebook pages being used solely for the purpose of running large quantities of political ads, deep in election campaigns," says Sam Jeffers of Who Targets Me.

"The law on this type of activity needs urgent improvement."

Many people were calling for tighter regulation before the election, and there is growing pressure in the United States and elsewhere for more transparency about who is behind online political ads.

Lisa-Maria Neudert says we do have a little more clarity about what is happening on Facebook and elsewhere, but it "shouldn't be just up to the social media platforms, the big technology firms, to release information about political advertising, but also the ones that are using it."

She says a whole lot of questions need answers.

"What are parties doing, what are political actors doing, what are they purchasing? Where are they purchasing it? We do know offline advertising is being archived. So what about digital content?"

For all the hype about the power of targeted ads sending thousands of individually crafted messages to each voter, it was one slogan, relentlessly pressed home in new and old media, that seemed to punch through: "Get Brexit Done".

Now the spotlight moves to the United States and the 2020 Presidential election, where far greater sums will be spent in an attempt to find the magic elixir of social media messages that will win over undecided voters.

- Published1 November 2019

- Published29 November 2019

- Published6 December 2019