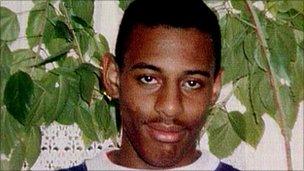

Stephen Lawrence: victim of a race attack

- Published

Stephen Lawrence was killed while waiting for a bus in south-east London

Two men have been found guilty of the murder of Stephen Lawrence, the black teenager stabbed to death by a gang of white youths at a London bus stop in 1993. The high-profile case has had a major impact on race relations in Britain. So who was he?

Stephen Lawrence was 18 when he died, and 18 years later his name is back on people's lips as Gary Dobson and David Norris are convicted at the Old Bailey.

His death in Eltham, south-east London, was a tragedy for his family but also became an event which led the nation to reflect on attitudes to race and justice.

A public inquiry into the unsolved murder - one of the most high-profile in Britain - accused the Metropolitan Police of "institutional racism" and incompetence.

The Macpherson Report's recommendations in 1999 also triggered a major reform of the justice system in England and Wales.

Film extra

Stephen was born on 13 September 1974 at Greenwich District Hospital in south-east London to Neville and Doreen Lawrence, who had emigrated from Jamaica in the 1960s.

He had two younger siblings - Stuart and Georgina - and the family grew up in Plumstead and attended Trinity Methodist Church in Woolwich, where Stephen was christened.

Stephen's character at home and school was shaped by an ethos of tolerance, religious faith and education.

His father Neville, now 69, was a carpenter, upholsterer, tailor and plasterer, while Doreen took a university course and became a special needs teacher.

As a young child, Stephen was good at most subjects at school, but loved to draw and paint and favoured art and maths.

By the age of seven he had resolved to become an architect - a career path he never deviated from.

At 16, his interest in design led him to set up a small business with a friend, designing and selling T-shirts, caps and jackets of well-known bands, rappers and politicians such as Malcolm X. He loved music, particularly soul and R&B.

Stephen planned to study architecture at university

As his confidence in himself and others grew, friends say he developed a good and trusting nature.

At one time he worked as a film extra alongside actor Denzel Washington in the film For Queen and Country.

Stephen also excelled out of the classroom. He was an active member of the Cambridge Harriers Athletic Club and once ran for Greenwich.

As a Cub, then Scout, he won badges for everything from cooking to sailing.

Like many teenage boys, he liked going out and girls.

At the time of his death, aged 18, he was studying A-levels in English, craft, design and technology, and physics at Blackheath Bluecoat Church of England School.

'Rebellious streak'

It was there that he met Duwayne Brooks, his close friend who witnessed the attack that led to Stephen's death.

Mr Brooks told the trial he met Stephen on the first day of school aged 11, and that by the time of his death, they were best friends.

He said he had begun a course at Lewisham College, while Stephen decided to stay on into the sixth form.

Stephen planned to study architecture at university and after his GCSEs, his family helped him find work experience with architect Arthur Timothy's practice.

The Royal Institute of British Architects later established an annual architectural award in his memory.

The Stephen Lawrence Prize is intended to encourage fresh, emerging talent working with smaller budgets.

Stephen's mother Doreen told Sir William Macpherson's judicial inquiry into the killing: "I would like Stephen to be remembered as a young man who had a future.

"He was well-loved and, had he been given the chance to survive, maybe he would have been the one to bridge the gap between black and white because he didn't distinguish between black or white. He saw people as people."

In 1998, Doreen set up the Stephen Lawrence Charitable Trust, which gives bursaries to young people who want to become architects.

Stephen had never been involved in crime, but the Reverend David Cruise - who led the church where the Lawrences worshipped - said it would be wrong to paint him as a saint.

Speaking after his death, he said: "Stephen was no goody-goody. He had his rebellious streak. Mrs Lawrence asked me to talk sense into him when he hadn't been behaving well.

"When I tried he just smiled his cheeky, knowing grin."

Stephen was a normal young man gifted with maturity and charm, he added.

"The irony is that the Lawrences behaved exactly how every black family is supposed to behave. They were law-abiding, close, stable, relaxed and upwardly mobile."

Marion Randall, the Lawrences' neighbour in Plumstead for 13 years, said after his death: "I feel like I have lost one of my own. But though my kids and Stephen's friends are now grown-up, just who Stephen would have been we will never know."

Stephen's father was 18 years old when he left his birthplace of Kingston, Jamaica, in 1960.

And it was the Caribbean that the family decided should be the final resting place for the teenager killed on a London street. Stephen's remains were buried 35 miles (56km) west of the capital in Jamaica's Clarendon parish. He lies beside his great grandmother.