The stolen childhoods of Kashmir in pencil and crayon

- Published

These are pictures of loss of childhood and innocence. They speak about a violent world outside shuttered homes. They reveal the terrors of the present and the fears for the future.

The colours are vivid. Red dominates, in blood and fire. Black is an ascendant colour, clouding the skies and scorching the earth. It's not dark yet, but it's getting there.

The artwork is by schoolchildren in Indian-administered Kashmir, home to one of the world's most protracted conflicts. These days, they mostly depict childhoods ruined by the violence of adults.

The meadows, streams, orchards and mountains that make their home "heaven on earth", as a Mughal emperor once exulted, is missing in much of their work. Stone-throwing protesters, gun-toting troops, burning schools, rubble-littered streets, gunfights and killings are some of the anxious, recurring themes on the canvas.

Last summer was one of the bloodiest in the region for years. Following the killing of influential militant Burhan Wani by Indian forces in July, more than 100 civilians died in clashes with security forces during a four-month-long lockdown in the Muslim dominated-valley.

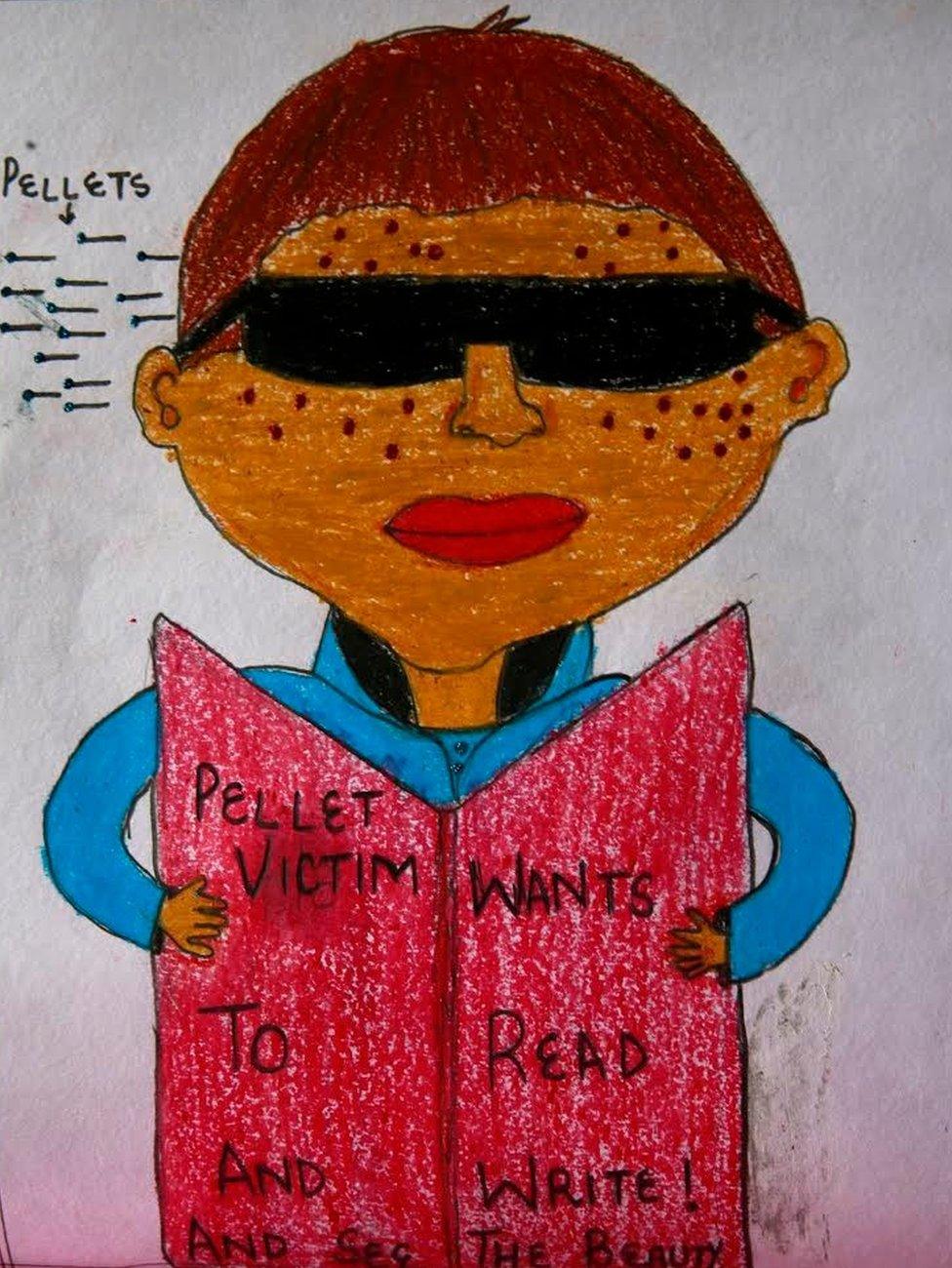

Security forces fired metal pellets from shotguns into protesting crowds, leaving many blinded. More than were among some 9,000 people injured in the protests. Most of them, according to reports, were "young, [and] were either blinded completely or lost their vision in one eye".

As violence spread on the street, schools shut. Children stayed indoors for months, drowning in the noise of TV news. At other times, they read and drew. They missed their friends and cricket games. Teachers gave lessons at home, and parents invigilated during home exams. One school even held an exam in a small indoor stadium.

"I would hide in a corner of my house' (Video production: Shalu Yadav and Neha Sharma)

When the schools reopened in the winter, teachers found many of the students irate, nervous and uncertain. They were children of government workers, businessmen, doctors, engineers, bankers and farmers.

They came looking "pale, like zombies", the principal of a leading school told me.

They cried and hugged each other. Having spent months cooped up in their homes in near-captivity, they asked their teachers why they had closed the school. Some of them behaved strangely. They screamed without any reason, banged the tables and broke furniture. Counsellors were called in to calm them down.

"There was anger, a lot of anger," the principal said.

Then, some 300 of them went to a school hall and sat down with paper and pastels. And they drew furiously.

"That's all they did on the first day. They drew what they wanted. They didn't utter a word. It was all very cathartic."

'I cannot see the world again'

The children drew mostly in pastel and pencil. Many wrote over their pictures, using speech bubbles, headlines and sentences.

In many of their pictures, the valley is on fire, and streets are littered with the black detritus of rioting against an incongruent backdrop of a blazing sun and birds in the skies.

Then there are young faces scarred and eyes blinded by pellets. It is a recurring, heart-wrenching theme.

"I cannot see the world again and cannot see my friends again. I am blind," says the subject of one such haunting image.

Childhood is the kingdom where nobody dies, as a poet wrote, but in Kashmir, children have lived in the shadow of death for as long as one can remember. There are bodies lying on the street, and there are people on fire in the paintings.

"These are the mountains of Kashmir. And here's a school for kids. On the left are army men and opposite them are stone-throwing protesters who are demanding freedom," said a schoolboy in Anantnag, explaining his drawing.

"When protesters throw stones at the army, the army opens fire at them. In the crossfire, a school kid dies and his friend is left alone."

The other recurring theme - and nightmare - is the burning down of schools. There's a powerful picture of children trapped in a school on fire, screaming, "help us, help us. Save our school, save us, save our future".

Others are angrier and more political.

There are drawings with pro-freedom graffiti, and signposts which say Save our Kashmir in pastels. Others extol Burhan Wani, and resonate with anti-India slogans. There are maps of Kashmir oozing red.

In another village in southern Kashmir, a prominent artist found children drawing Indian flags fluttering on top of their houses.

Rival neighbours

A scowling face of a man split into two is a metaphor for the bitter and festering rivalry between India and Pakistan, and the tragedy of a land sandwiched between the rival neighbours.

There's a heart-breaking pencil drawing of a mother waiting for her son. The children also vent their frustration over the during the protests.

Five years ago, Australian art therapist Dena Lawrence conducted some art lessons with young people in the valley. She found black was the predominant colour in their paintings, and most of them reflected

Kashmiri artist Masood Hussain, who has been judging art competitions for children aged four to 16 for the past four decades, says their subjects have changed.

"They have gone from the serene to the violent," he tells me. "They draw red skies, red mountains, lakes, flowers and houses on fire. They draw guns and tanks, fire-fights and people dying on the street."

Arshad Husain, a Srinagar-based psychiatrist, says the artwork of the children in the valley betrays their collective trauma.

"We think children are too young to understand. That's not true. They absorb and assimilate everything around them. They express it in their own way," he says.

"Mind you, most of this artwork is coming from children who stayed at home. Imagine the children on the streets who are closer to the violence."

It is all reminiscent of : weeping children, the twin towers on fire and being yanked off the ground by Osama Bin Laden against a blood-red skyline, a scarred girl wearing an I Love New York T-shirt.

In Kashmir, where fairy tales quickly turn into nightmares, hope is not extinguished yet.

Let our future be bright, make us educated, don't make this crisis a reason for darkness, pleads a girl in a drawing. It's never too late.

Illustrations gathered from children in Indian-administered Kashmir