Eurozone debt crisis: Greece's wild card

- Published

- comments

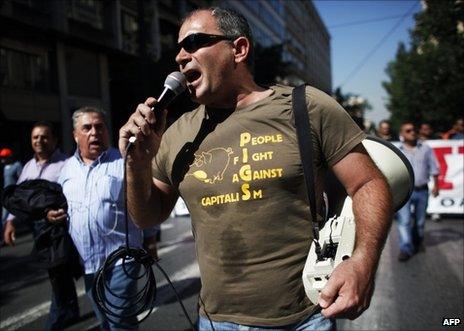

Popular discontent in Greece may disrupt the economic rescue

When the G20 finance ministers gather in Paris they face a stark fact: that nearly a year and a half since Greece received its first bailout, the crisis remains unresolved. Europe's leaders will be asked yet again what they are going to do with Greece.

Sure, the country now looks certain to receive another tranche of bailout money next month. A cool 8bn euros (ВЈ7bn; $11bn). But it is a band aid and everyone knows it. For since May 2010 the Greek economy has shrunk and its debt mountain has grown. Next year the debt-to-GDP ratio could reach 172%.

Most economists and bankers believe Greece is insolvent. So, increasingly, do officials and politicians in Berlin. Senior economists are examining what would happen if Greece were forgiven some of its debts, if it did not have to pay back a chunk of its debt to the banks.

Built into the second Greek bailout, negotiated on 21 July, was a write-down by banks. They would take a 21% hit. But self-evidently that is not enough. There is widespread agreement that half of Greece's debts need to be written off if it is to have a realistic chance to find stability again. So banks and other financial institutions may have to take a 50% hit on their investments.

That is why there is now great attention being given to the health of Europe's banks. A couple of stress tests have not convinced. No one is sure what the impact of a Greek default would be on the banking system. So there is a rush to strengthen balance sheets. And that is the aim: to limit the shock waves from a Greek default.

But as with almost every step in the crisis a possible solution brings new risks. For if banks need to build up their capital it might well cause banks to slow down their lending. And that risks freezing up the financial system. That was the warning from one of the biggest figures in global banking - Josef Ackermann, chief executive of the huge Deutsche Bank.

All of this has to be weighed and argued over in the days ahead. As one official put it to me, "you can't have a convincing plan without reducing Greek debt".

But there is another factor in all this, a wild card: the Greek people.

Saying 'no'

It is just possible that the Greek people will have their say, that they will simply refuse to go along with austerity plans demanded by outsiders, their creditors.

What happens if a people simply says "no"? What happens if, through many small and not-so-small actions, they sabotage the plan?

One of the new austerity measures involves using the electricity bills to raise funds from a property tax. Yet protesters have occupied the printing offices of a Greek power company. If there are no bills, no-one need pay.

Arguably the key ministry in this crisis is the finance ministry. Yet finance ministry officials have called a 10-day strike from from 17 October.

The country is crucially dependent on tourist income. Yet yesterday protesters were blockading the Acropolis. There are plans next week for the seamen who operate the ferries to the islands to strike. Garbage piles high in the streets as municipal workers blockade the landfill sites.

And my eye was caught by this paragraph in a Reuters despatch: "Lawyers refused to appear in court, doctors were due to rally outside the health ministry, while a group of patients suffering from kidney cancer rallied outside the finance ministry which was occupied by striking officials."

It is easy sometimes to exaggerate the impact of street protests. There is often a silent majority. But with Greece I am no longer so sure.

The impressive Finance Minister, Evangelos Venizelos, has warned of a vicious cycle, that the strikes are leading Greece's creditors to doubt the country can meet its promises and so more austerity measures might be needed.

He tells it to the people how he sees it - that there is no alternative to going along with a plan drawn up the troika of the EU, the IMF and the ECB.

There are summits and then there are the streets. In the days ahead there will be much negotiating over how to save the eurozone but the Greek people - not just public sector unions - may simply upset the plan.