Pakistan floods push food prices higher

- Published

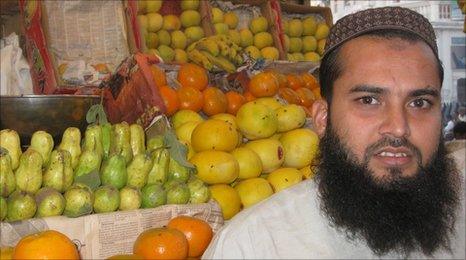

Business has plummeted for stallholders such as Shafiq-ur Rehman

The UN's agriculture body, the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), says food prices in Pakistan have risen 10% since floods hit the country in August and wiped out much of its produce. Jill McGivering visited Sukkur in Sindh province, one of the areas worst affected by the floods, to see how rapidly rising prices are affecting local shopkeepers and customers.

The main market in Sukkur is known by locals as Clock Market.

Its stalls run down a maze of alleyways which lead away from a central roundabout with an elaborate clock tower.

At the end of the afternoon, just before dusk, the whole area is hectic with traffic, from motorised rickshaws and motorbikes to donkey carts. It is also busy with shoppers.

Rotting food

Shafiq-ur Rehman is a young man wearing a round tribal hat. His fruit stall is well-positioned, close to the clock tower, and laden with produce: coconuts, pomegranates, several kinds of oranges, bananas and apples.

The distribution of food supplies after the floods has caused major problems for the authorities

But although the fruit looks delicious, no-one is buying.

He has had to put his prices up dramatically, he told me.

The roads into Sukkur have been badly damaged by the floods. His fruit comes by lorry from other parts of Pakistan, including Punjab, Baluchistan and Rawalpindi.

But now, since the floods, those journeys take four or five days. Some of the fruit rots before it even reaches him.

The extra petrol also makes the extended journeys very expensive. They are additional costs which he has to pass on to the shopper.

He gave me some examples. Oranges which normally cost 40 rupees (46 cents; 30p) a kilo are now 50 rupees.

Pomegranates have more than doubled in price, from 60 or 70 rupees a kilo to 150 rupees ($1.75; 拢1.13). Basically most people can't afford to buy fruit any more, he told me - business has plummeted.

Farther down, I met Hajji Yaqoob, a middle-aged man with a large stomach and long white beard.

He was sitting cross-legged behind his vast array of vegetables - cabbages, tomatoes, onions, okra, aubergines and many other kinds.

Washed away

As I arrived, a woman, dressed all in black and with her face covered, was buying a small bag of okra from him.

Many people have been hit twice by the flooding - loss of possessions and rising prices

As he weighed them out on old metal scales, she told me that the new prices made most items unaffordable.

Before the floods, she used to buy lots of different kinds of vegetables, she said.

Now she was buying a little of only one. Even her okra cost 80 rupees a kilo, compared with 50 rupees before the flood.

Hajji Yaqoob said that, before the floods, he sold vegetables which were grown around Sukkur.

But because the local crops had been washed away, he had to look farther afield, from other provinces. That was one of the main reasons for the high prices.

Agriculture is the backbone of Pakistan's economy.

The damage to crops caused by the floods is already having a serious effect on the cost of living.

Many families here are hit twice.

They have suffered because their own produce and possessions have been lost.

And now they are being hit a second time, by escalating prices which mean that the little money they still have in their pockets is buying significantly less.