Navajo Nation: The people battling America's worst coronavirus outbreak

- Published

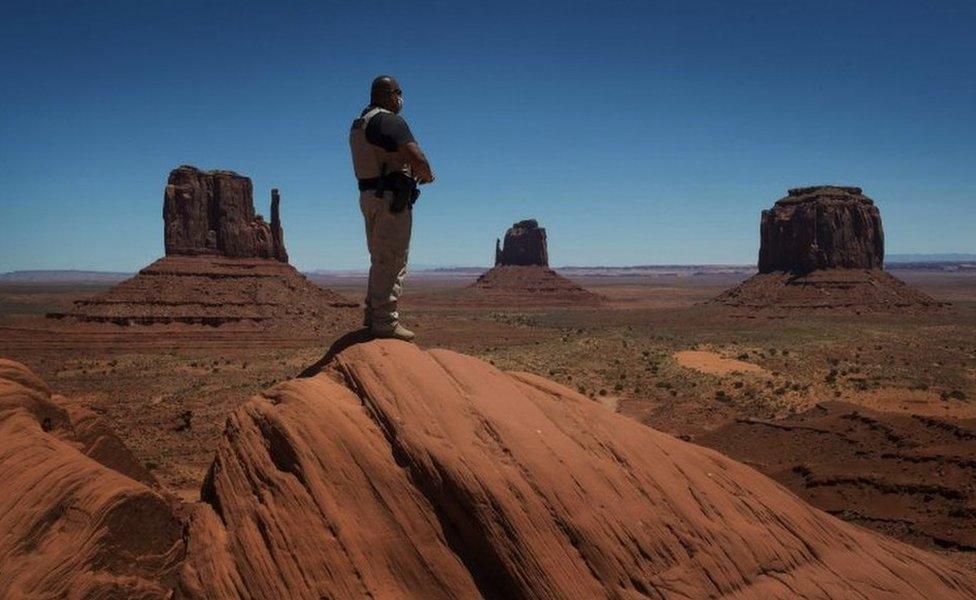

The Navajo Nation, a Native American reservation, spans three states

When Valentina Blackhorse tested positive for coronavirus, she texted her sister and told her not to worry.

A former pageant queen, Valentina was known for her love of her Native American Navajo heritage, her passion for helping others and her playful sense of humour. She doted on her one-year-old daughter, Poet, and worked as a government administrator, with dreams of leading her people some day as Navajo president.

When coronavirus reached the reservation on which she lived, Valentina warned her family to stay indoors and take precautions. Weeks later her boyfriend Bobby fell ill and she tended to him at their home in Kayenta, a small town near the sandstone buttes of Arizona's Monument Valley.

She'd lived with rheumatoid arthritis her whole life, but soon her joint pain started to feel different, and breathing wasn't so easy. She took herself for a test and the results came back a week later, confirming her fears. The next day, when Valentina's breathing got worse, Bobby rushed her to a health clinic. She died hours later, aged 28.

"She overcame a lot of things in her life," said her sister, Vanielle. "I thought she was strong enough to pull through."

"If we had better resources, maybe Valentina would still be alive"

Valentina was one of the youngest victims of coronavirus in the Navajo Nation, a Native American reservation grappling with what is America's worst outbreak.

Since Covid-19 was first reported in the Nation on 15 March, infection rates per capita have become the highest in the country when compared with any individual state.

As of 14 June, 6,611 cases have been confirmed. More than 300 people have died after contracting the virus as well - a toll higher than 15 states.

The Navajo Nation is the largest reservation of its kind, in both size and population. More than 173,000 people live within its borders, in pockets of communities spread across the deserts and canyons of Utah, Arizona and New Mexico. If it were a state, the Nation would be larger than 10 others.

The Navajo - or DinƩ, as they call themselves - have lived in the region for centuries, but the Navajo Nation is an American construct. After US expansion forced thousands of Navajo to leave their homes, America carved out a stretch of land where they could maintain some sovereignty. In return, the federal government pledged to support its people with funding for education, healthcare and other services. The Navajo have contributed much to America's development. Perhaps most famously, Navajo soldiers invented a military code, based on their language, that kept American communications secure during World War Two.

But as coronavirus has swept through the reservation, it has underscored many of the social and economic inequalities that continue to affect the tribe - all contributing to one another, and all making the outbreak worse.

"If we had better resources, maybe [Valentina] would still be alive," said Vanielle.

The Navajo Nation's vast scale has made it difficult for residents to access resources during the outbreak

Many residents struggle with money. The reservation's unemployment rate is approximately 40%, and a similar number live below the poverty line, earning less than $12,760 (Ā£10,191) a year.

These factors exacerbate health problems among the Navajo and a third of the population suffers from diabetes, heart conditions and lung disease. In some cases, people have fallen ill after years of radiation exposure from hundreds of abandoned uranium mines dotted around the desert.

Severely limited access to healthy food also plays a role. The Navajo Nation spans 71,000 sq km (27,413 sq miles) but has only 13 grocery stores, forcing many residents to drive for hours to towns outside the reservation with better facilities. It is common for people from different households to travel in one vehicle during these excursions because they are unable to afford petrol, further heightening their risk of catching coronavirus.

Relief efforts have been hampered by limited healthcare resources, too. The reservation's dozen medical facilities hold just 200 hospital beds - approximately one bed for every 900 residents, and a third the national rate. As a result, some coronavirus patients have been moved to makeshift quarantine facilities, while others have been transferred to hospitals outside the reservation.

Many homes are multi-generational as well, making it easier for the virus to spread to elderly and vulnerable residents. A third of households have no access to running water or electricity either, making it hard for thousands of people to wash their hands regularly and to stave off infection.

"This is something that is year-round, it's been going on since we were put on reservations," says Emma Robbins, head of DigDeep, a charity that's delivering bottled water and improving access to running water in the Nation.

Miss Navajo Nation Shaandiin P. Parrish is one of the volunteers who have helped distribute food and water

Ms Robbins was born on the reservation. She now lives nearly 600km (373 miles) away in Los Angeles, California, but is unable to return due to travel restrictions.

"I fear for my family and I fear for my friends," she told the “óĻó“«Ć½, tearfully. "Hearing these stories and not being able to go home is really hard and I feel so hopeless."

But despite their hardship, Ms Robbins says she feels frustrated by the tone of victimhood that often colours discussions about her tribe.

"It's really trendy to do things surrounding the Navajo Nation in terms of 'Oh look how bad it is here,' but I don't think people highlight enough of the amazing efforts on the ground and the positivity," she adds.

About a third of households on the reservation have no running water

In response to the outbreak, the federal Bureau of Indian Affairs told the “óĻó“«Ć½ it had taken "unprecedented actions to support Indian Country," providing the Navajo with protective equipment, contamination trailers, and other technical assistance.

The Navajo Nation has also received $600m under the CARES Act, a $2tn economic stimulus package to shore up local economies and communities during the pandemic. But local authorities only received the money a month after the bill was signed into law. In the meantime, the Navajo and 10 other tribes successfully sued the US Treasury over funding disparities in the CARES Act for Native American groups.

In the midst of federal funding delays, the Navajo Nation had to rely on donations and its own resources in the crucial early weeks of the outbreak. Navajo President Jonathan Nez has co-ordinated the distribution of food and medical supplies to local residents, and introduced some of the strictest lockdown measures in the US - imposing a series of 57-hour weekend curfew.

Locals are stepping in to help as well. More than $5.1m has been raised for the 'Navajo & Hopi Families Covid-19 Relief Fund' - a crowdfunding campaign started by former Navajo attorney general Ethel Branch. In an unusual twist, thousands of dollars have come from donors in Ireland - many paying respect to Choctaw Indians who, in 1847, donated $170 towards relief efforts in Ireland during the Great Hunger. With help from volunteers, Ms Branch has used the donations to deliver food, water and hand sanitiser to thousands of residents. But poor infrastructure has presented a challenge at times.

"There's one community that's really isolated and we're trying to figure out how to get food there," she told the “óĻó“«Ć½. "The easiest way would be to go directly, but it's all dirt road, and if we stick to the pavement, that adds on another hour and a half."

Navajo President Jonathan Nez (L): "There's still much uncertainty right now, but I'm hopeful."

Language barriers have also been a deciding factor in the Navajo Nation's response to the outbreak.

As with all public communications, it shares coronavirus updates in the Navajo language as well as English. This is driven by desires to maintain cultural heritage, but is a practical step as well because some residents speak only Navajo, or have limited English skills. In Navajo, coronavirus is translated as Dikos NtsaaĆgĆĆ-19, or Big Cough-19. But several residents have told the “óĻó“«Ć½ they believe this translation downplays the severity of coronavirus.

Among them is Agnes Attakai, a Navajo Nation native and a director at the University of Arizona's School of Public Health. She said a renaming should be explored in consultation with traditional Navajo healers.

"You have to be respectful of using the language and not invite the negativity of that particular illness," said Ms Attakai. "Once you start respecting and addressing it appropriatelyā¦ people will be engaged more to change their behaviours rather than linking it up with cough and pneumonia."

But Navajo President Jonathan Nez said it was "unfair" to suggest the translation did not adequately convey the dangers.

"That's an excuse being played out there," he told the “óĻó“«Ć½. "We're respecting our elders and our traditional teaching by avoiding utilising the word death and anything that would bring negativity or hardship on our people."

Looking ahead, as surrounding states begin easing lockdown measures, many residents are concerned about a possible second wave of infections hitting the reservation.

"There's still much uncertainty right now, but I'm hopeful," said President Nez. "You've got to be hopeful to be the leader of the Navajo people."