Snakebites: The search for a new treatment

- Published

- comments

New drugs are urgently needed to treat snakebites say scientists.

A multi-million pound fund has been set up to find a new treatment for snakebites which kill up to 138,000 people each year.

Two major health organisations - the World Health Organisation (WHO) and the UK's Wellcome Trust - are giving money to solve the problem.

How serious is the problem?

The WHO calls snakebites "the world's biggest hidden health crisis".

It says one person dies from a bite every four minutes. Hundreds of thousands of others are left seriously injured.

Snakebites in the UK are rare and when they do happen, they are usually not serious. They mainly affect people living in some of the poorest areas of Africa, Asia and Latin America where more dangerous snakes live.

What treatment is used now?

The treatment used now, anti-venom, has been used for more than a 100 years.

Venom from a snake is injected into a horse. Antibodies form in the horse's blood to protect it and these are taken out to make the anti-venom.

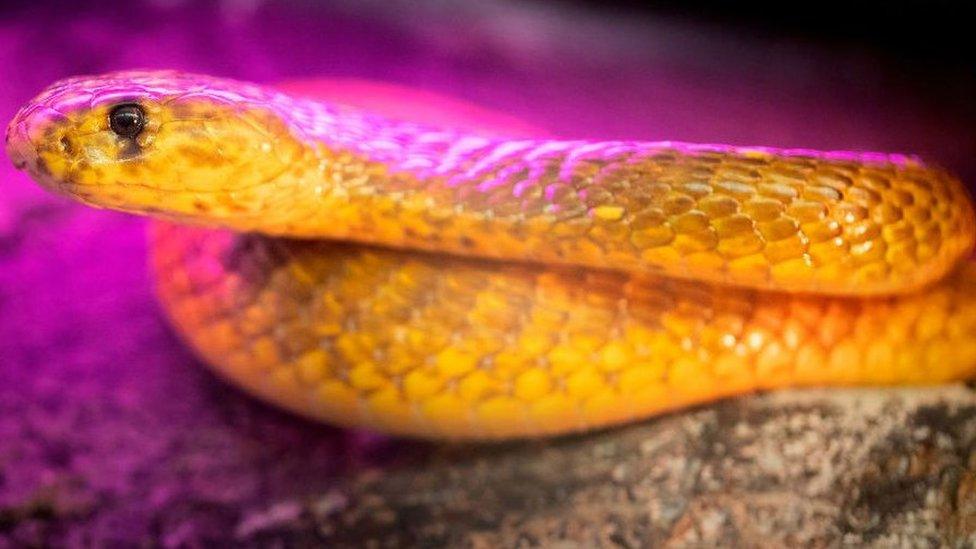

Venom being extracted from a snake.

The problem is that this method can be very expensive, may not work and can cause lethal allergic reactions.

It will work for bites from the same type of snake but not necessarily any others. Anti-venom exists for only about 60% of all the snakes in the world.

What can be done?

The Wellcome Trust is giving 拢80m to invest in new treatments and better access to effective anti-venoms.

Venomous snake

The WHO wants a plan to halve the number of deaths and disabilities caused by snakebites by 2030.

Dr Williams, an expert on snakebites at the World Health Organization says:

"It's about having safe, effective anti-venoms, trained health workers and people being taught how to prevent snakebite, and what to do when someone is bitten."

- Published21 October 2015

- Published27 September 2012

- Published25 April 2019