Space: Proxima b confirmed by scientists as orbiting our nearest star

- Published

- comments

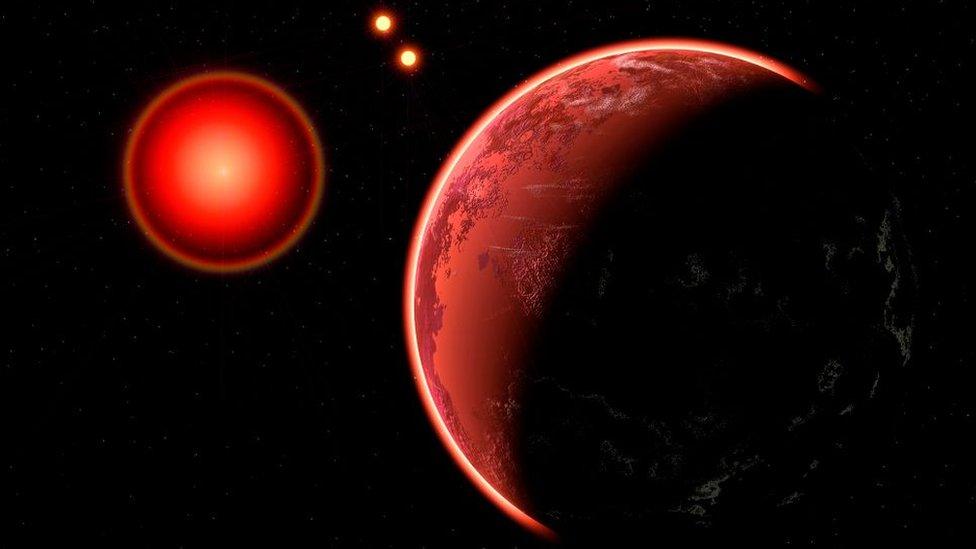

Proxima Centauri is the closest planet to our solar system

A team of international researchers have confirmed that the closest star to our solar system is currently being orbited by an Earth-sized planet.

Proxima Centauri is the star nearest to the Earth's solar system.

It's being orbited by a planet known as Proxima b, which was actually discovered back in 2016 using the High Accuracy Radial velocity Planet Searcher, or HARPS for short. It's a piece of equipment, called a spectograph, used to find new planets and it has played an important role in the world of astronomy.

What is a spectrograph?

Spectrographs are instruments used by astronomers. These devices are able to break up light collected by a telescope into its various colours, or wavelength. This is be used to work out the chemical make-up of space objects like stars or planets.

However, a special piece of equipment which is three times as accurate as HARPS has been used to confirm the planet's existence. The ESPRESSO spectrograph - which is currently installed on a huge telescope in Chile.

"We were already very happy with the performance of HARPS, which has been responsible for discovering hundreds of exoplanets over the last 17 years," said professor Francesco Pepe who is based in the Astronomy Department at UNIGE's Faculty of Science. "We're really pleased that ESPRESSO can produce even better measurements, and it's gratifying and just reward for the teamwork lasting nearly 10 years."

So what do we know about the planet? Well, it's thought to be 1.17 times the mass of Earth which is a little smaller than scientists' previous estimate. It's found in something known as the habitable zone of its star Proxima Centauri which it orbits every 11.2 days.

Brian Cox's The Planets: Everything you need to know

Proxima b is roughly 20 times closer to Proxima Centauri than the Earth is to the Sun, but it gets similar levels of energy from its star. It's thought its surface temperature could mean that any water on the surface may contain life.

However, the Proxima star is an active red dwarf which blasts its planet with around 400 times as many X-rays than the Sun hits the Earth with, so whether life can actually develop on its surface is something scientists are unable to answer at the moment.

"Is there an atmosphere that protects the planet from these deadly rays?" said Christophe Lovis who is a researcher in UNIGE's Astronomy Department. "And if this atmosphere exists, does it contain the chemical elements that promote the development of life (oxygen, for example)? How long have these favourable conditions existed?"

The researchers are looking to find answers to some of these big questions and they'll also be making use of more cool scientific instruments to help them out.

- Published4 June 2019

- Published7 February 2020

- Published9 March 2020