Why is a space camera taking super close-ups of broccoli?

- Published

- comments

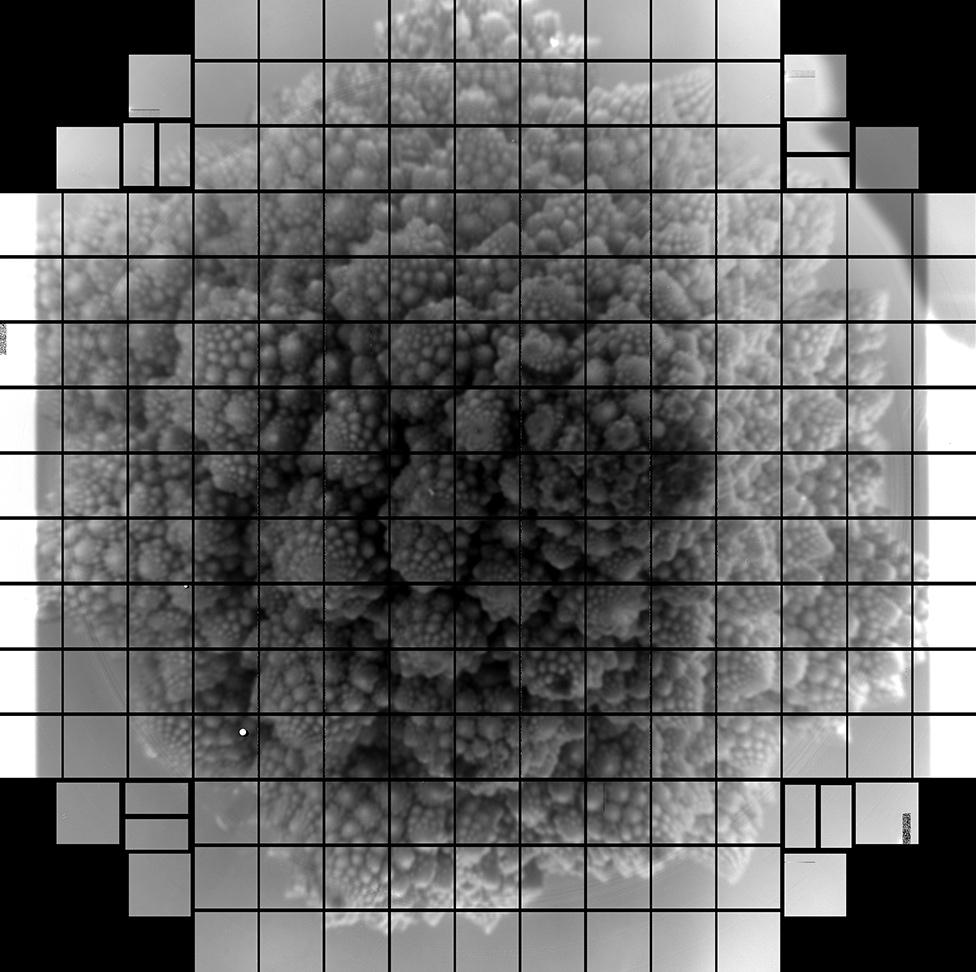

A head of broccoli was used to test the super camera

A camera designed to photograph 20 billion galaxies over the next decade has been tested by taking a photo of, er, broccoli.

The camera which - once fully built - will be the size of large car, can take photos that are 3.2 billion pixels, which is the highest resolution ever.

That means that a photo of a golf ball could be taken from 15 miles away and images taken by the camera would need 378 4K ultra-high-definition TVs to be shown.

The focal plane on the camera, which is the distance between the camera lens and the perfect point of focus in an image, is 64cm wide and has 189 individual sensors. That's a lot!

OK - so why broccoli?

Ok - it might sound strange that a camera that's so powerful has been used to take a photo of broccoli, but the complex shapes found on the vegetable are a good way to check the camera sensors are capturing lots of detail.

Although cool photos of food might do well on Instagram, this camera has a different purpose as it will be fitted to the Vera Rubin Observatory in Chile in South America.

While there, the camera will be used to take large photographs of the sky for ten years, in doing so it will keep track of the positions of billions of stars and galaxies, but it will also catch anything that moves or flashes.

"If we're to complete this survey of the sky, we're going to need a big telescope and a big camera," explained observatory director Steve Kahn.

"We'll get very deep images of the whole sky. But almost more importantly, we'll get a time sequence. We'll see which stars have changed in brightness, and anything that has moved through the sky like asteroids and comets."

However, there could be a problem as satellites might streak through the camera's field of view and ruin its images.

Earlier this year, Elon Musk's Space X company launched a chain of satellites which will form part of a massive network of 12,000 low-orbiting space craft.

Prof Kahn says the observatory has reached out to Elon Musk and are working to find a solution, meanwhile he hopes other satellite companies, including the British-Indian-owned OneWeb will do the same.

It's expected that the observatory's camera will start taking images of the sky - instead of heads of broccoli - in late 2022.

- Published10 September 2020

- Published8 September 2020

- Published21 August 2020