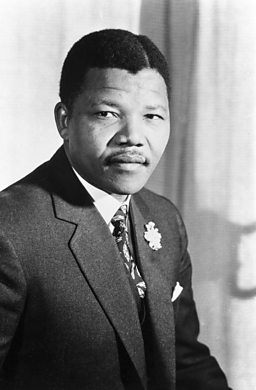

The early years of Nelson Mandela

In 大象传媒 Radio 4’s podcast, History’s Youngest Heroes, Nicola Coughlan shines a light on extraordinary stories of rebellion, risk, and the radical power of youth, looking at young people throughout history who have changed the world.

One episode focuses on Nelson Mandela, the South African leader who many today remember as the dignified elder statesman who was imprisoned for 27 years by the country’s apartheid regime. After his release in 1990, Mandela negotiated an end to racial segregation. He became its first Black president – and a revered figure on the global stage.

Yet his political career started when he was a much younger man. History’s Youngest Heroes looks at the early development of Mandela’s political identity through the Defiance Campaign in the 1950s.

Who was Nelson Mandela?

He was born Rolihlala Mandela in 1918 in the countryside of the Eastern Cape. When he was eight years old, his primary school teacher gave him the English name Nelson. Though his family were Thembu aristocrats, his parents lived in a simple hut with no electricity or running water. His father died when he was 12, and he was sent as a foster child to the regent of the Thembu Kingdom, Jongintaba Dalindyebo. He was sent to boarding school, then enrolled at Fort Hare, a university for Black Africans. He intended to become a court interpreter – a prestigious role that would place him in the high echelons of the Black elite.

Why did he leave this comfortable life?

At Fort Hare, a student protest broke out over the quality of the food and the treatment of a canteen worker. Mandela was elected to the students’ representative council: the rest of the representatives capitulated, but he backed the protesters and was suspended. Jongintaba was furious with him, and arranged a marriage for him as well as for his own son, Justice. Neither Mandela nor Justice wanted this – so they sold some of Jongintaba’s cattle and used the money to flee to Johannesburg. There, a cousin introduced him to a powerful Black activist, Walter Sisulu: a socialist-leaning member of the African National Congress (ANC), which advocated for the rights of Black South Africans.

What was life like for Mandela in Johannesburg?

Mandela lost interest in the idea of working at court and instead hoped to train as a lawyer. Sisulu found him a placement in a small White Jewish law firm. Mandela had rarely encountered any White people. His life among the Black elite had insulated him from the racism and segregation common in South Africa. Now, all his colleagues were White, and they expected him to use separate teacups: even junior secretaries would send him on errands to buy their shampoo. He became the only Black student in the law school at the University of the Witwatersrand, and was not allowed to use the swimming pool, join a club, or go to dances.

How did he enter politics?

Mandela attended some ANC meetings during the early 1940s, but felt the organisation was rather too gentlemanly in its demands and out of touch with younger Black people who were arriving in Johannesburg to help in the efforts to fight the Second World War. More radical organisations, including trades unions and the mostly White and Indian-led Communist Party, were growing among these young people. Mandela decided to work within the ANC and helped build a new ANC Youth League.

From the Defiance Campaign onward, going to prison became a badge of honour among Africans.Nelson Mandela

What was apartheid?

There had been racial segregation in South Africa for a long time, but by 1948 the incumbent government held vague notions of integration. That year, though, the South African National Party unexpectedly won the election, pledging a strict policy of apartheid – meaning “separateness” – which would enshrine racial segregation in law. The system privileged those defined as White, and instituted political and economic discrimination against those defined as Indian, Coloured – meaning mixed race – or Black.

What was the Defiance Campaign?

In the spring of 1951, Mandela was 32 and president of the ANC Youth League. He persuaded the ANC to adopt a programme of non-violent mass action called the Defiance Campaign: breaking segregation laws, ignoring curfews, standing on the White side of the platform at the train station, and so on. Walter Sisulu argued they should draw on the support of Indian and Coloured people, but Mandela had set himself up as an Africanist – arguing that Black people should fight alone. However, at the ANC meeting in December 1951, he switched to supporting multi-racial action. The ANC made him volunteer-in-chief of the Defiance Campaign. At a rally in Durban on 22 June 1952, Mandela addressed a crowd of 10,000 people and set the campaign in motion.

What happened to the Defiance Campaign?

It was unusually successful in recruiting volunteers beyond the usual youth and student activists: more than 8000 Black people were arrested, including respectable figures such as doctors and lawyers. Though the campaign was non-violent, there were incidents of violence – and a violent response from the authorities. In Port Elizabeth, when some Black protesters threw stones at police trying to break up their gathering, police opened fire and killed a number of them. In a separate incident in East London, a White Catholic nun was killed by a mob. Though Mandela stated that violent incidents were not connected to the Defiance Campaign, the government linked them, arrested him, and barred him from further public appearances.

The Defiance Campaign did not overturn apartheid, but ANC membership grew and Mandela was impressed that many more South Africans proved themselves ready to resist. “From the Defiance Campaign onward, going to prison became a badge of honour among Africans,” he wrote. It took more than 40 years to overturn apartheid – and he would do it.