Art as power tool: How Charles II overruled austerity

6 December 2017

The 'Merry Monarch' presided over a hedonistic court and fathered 12 illegitimate children. But, after the years of Cromwellian austerity, science and the arts flourished under Charles II. At a new Royal Collection exhibition, WILLIAM COOK discovers how Charles projected power through art.

Here at Buckingham Palace, the Queen’s Gallery is a hive of frantic industry, as the Royal Collection’s curators prepare for the most important show of the year. The floor is strewn with bubble wrap. Precious prints and paintings are stacked against the walls.

Art was a useful tool in reasserting the restoration of the monarchyLauren Porter, curator

One of the curators, Lauren Porter, guides me through the maze. As she explains, this exhibition sheds fresh light on an era most of us hardly know about – the reign of Britain’s ‘Merry Monarch,’ Charles II.

"What’s particularly exciting about this exhibition is that it’s the first time that the is focusing on Charles II as a collector of art – showing how he used art to express his power," says Lauren. "Art was a useful tool in reasserting the restoration of the monarchy."

Like most British monarchs, Charles II remains familiar, if at all, through a few folkloric clichés: he hid in an oak tree to escape from Cromwell’s soldiers (hence all the British pubs called The Royal Oak); he had an eye for the ladies (especially ‘pretty, witty’ actress Nell Gwyn).

However his 25 year reign was also an era of lively creativity - not only in the arts, but in science too. "He had a wide range of interests," says Lauren. "It’s not all fun and games."

Exiled on the Continent, Charles II returned to Britain in 1660 after the death of Oliver Cromwell, the puritanical Lord Protector who’d executed his father, Charles I.

After the austerity of the Commonwealth, he ushered in an age of lavish display, reopening the theatres, which Cromwell had shut down.

Like a 17th Century rock star, Charles II liked to have a good time... all the time ("the King do mind nothing but pleasures, and hates the very sight or thought of business," wrote Samuel Pepys) but he also enabled more serious men to prosper.

Highlights include The Massacre of the Innocents by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, drawings by Hans Holbein and Leonardo da Vinci, and some splendid tapestries

He was the first patron of the , which led the world in science and numbered Isaac Newton among its members. He supported Christopher Wren, who rebuilt the capital after the , transforming it into a modern metropolis, with at its centre. John Dryden, the first Poet Laureate, called him "a great encourager of the arts."

Charles I had assembled an amazing art collection, including Renaissance masterpieces by Raphael and Titian, and contemporary paintings by Rubens and Van Dyck. Cromwell sold off this collection - Charles II did his best to get it back. Many works remained abroad (they form the basis of a new exhibition at London’s Royal Academy in January) but Charles II regained a good many, including Van Dyck’s magnificent equestrian portrait of Charles I.

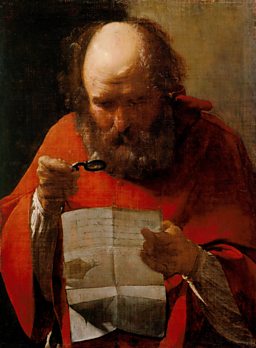

Charles II also built up a decent art collection of his own. It’s this collection that makes up the backbone of this intriguing exhibition. Highlights include The Massacre of the Innocents by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, drawings by Hans Holbein and Leonardo da Vinci, and some splendid tapestries. He also patronised contemporary painters, like the Dutch portraitist Peter Lely.

All Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2017

The painting in the middle (c.1662–64), by Jacob Huysmans, shows Catherine of Braganza, the Queen of England, Scotland and Ireland by her marriage to Charles II. it is flanked by two portraits by Sir Peter Lely, from a series of ten 'Windsor Beauties' - so-called because the collection was housed in the Queen's bedchamber in Windsor Castle. On the left, Barbara Villiers, Duchess of Cleveland, c.1665 is Lely's portrait of one of Charles II's many mistresses; she bore five of his children. Elizabeth Hamilton, Countess of Gramont, c.1663, on the right, depicts an Irish-born courtier.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder - The Massacre of the Innocents, 1565-7 | Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2017

Yet the thing that brings this show alive isn’t fine art but gutter journalism. There are engravings of the King’s mistresses ("illustrious strumpets as have debauched great Princes, and contributed more perhaps to the ruin of the Kingdom than all the wars, fires, plagues and plots").

The in-fighting between these women would have delighted a modern tabloid editor. Nell Gwyn once spiked a rival’s food with laxatives, so she couldn’t "serve" the King.

The most lurid piece of tabloidese is the reporting of the Popish Plot - a Jesuit conspiracy to murder Charles II and replace him with his younger brother, James, a devout and unrepentant Catholic. The plot was exposed by a failed clergyman and sometime sailor called Titus Oates, and 35 conspirators were executed on his say-so.

Only then was it revealed that Oates had made the whole thing up. He was merely flogged and imprisoned for this fake news (there was no death sentence for perjury). Freed and pardoned after a decade in prison, he was granted a generous pension and lived to the (relatively) ripe old age of 57.

In a contemporary news sheet (the precursors of today’s newspapers) the scandal is depicted like a modern comic strip, complete with speech bubbles. I particularly enjoyed the graphic depiction of the conspirators saying their last words on the gallows, and Oates being thrashed across the bare buttocks.

Charles II died in 1685, of natural causes, and was succeeded by his brother, James. Unlike his elder brother, James was a useless monarch, and was usurped by William III in the ‘Glorious Revolution’ of 1689. This exhibition ends with James II’s brief reign, which provides a vivid contrast to Charles II’s far longer, and far more successful, tenure. It’s a contrast that suggests the ‘Merry Monarch’ was actually a lot smarter than he liked to make out.

- is at The Queen's Gallery, Buckingham Palace, London SW1, from 8 December to 13 May.

- Read about the , beginning January 2017.

More from 大象传媒 Arts

-

![]()

Picasso鈥檚 ex-factor

Who are the six women who shaped his life and work?

-

![]()

Quiz: Picasso or pixel?

Can you separate the AI fakes from genuine paintings by Pablo Picasso?

-

![]()

Frida: Fiery, fierce and passionate

The extraordinary life of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, in her own words

-

![]()

Proms 2023: The best bits

From Yuja Wang to Northern Soul, handpicked stand-out moments from this year's Proms