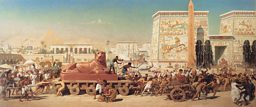

Handel's 'Israel in Egypt'

As Radio 3 broadcasts Handel's early oratorio Israel in Egypt, recorded in May 2019 by the ����ý Singers and the Academy of Ancient Music conducted by Gergely Madaras, we explore this dramatic retelling of the Israelites’ exodus from Egypt.

Handel was at the height of his fame when he composed his oratorio Israel in Egypt in 1737–8. But, with this being one of his earliest works in the form (his breakthrough Messiah came three years later in 1741) and with audiences used to the greater opportunities for solo vocal display offered by his earlier Italian operas, the initial reaction was lukewarm.

The many, not the few

More than most of Handel’s oratorios, Israel in Egypt focuses on the choir, not the vocal soloists. This neatly conveys the nature the story – that of the suffering of the Israelites in captivity in Egypt and of Moses leading them to freedom. Rather than adding commentary as bystanders, the chorus is key to the action, representing entire nations and peoples. Handel threw all his ingenuity into the choral writing, working in an array of devices and textures that create endless variety. No wonder Israel in Egypt became a popular staple in the British choral society boom of the 19th century.

A drama of biblical proportions

The action falls in two parts (at least in the later, two-part version performed here: the original version was in three parts). Central to the narrative in Part 1 are the 10 plagues unleashed upon the Egyptians. A master of word-painting in music, Handel introduced leaping violin lines for ‘Their land brought forth frogs’, scurrying strings for ‘all manner of flies and lice’, robust choral singing with thundering timpani and brass for ‘He gave them hailstones for rain’, and stabbing chords at ‘He smote all the first-born of Egypt’. Perhaps most effective of all is the ‘thick darkness over the land’, expressed with slow, expansive harmonies that truly convey ‘even darkness which might be felt’.

Joyful liberation

Rather than continuing the narrative, Part 2 is an extended celebration after the Israelites’ escape via the miraculously parted waters of the Red Sea. Most of Israel in Egypt’s relatively small sprinkling of arias and duets fall into this part, offering quieter contrasts to the choruses.

Handel at a crossroads

It was in 1738, the year he completed Israel in Egypt, that a life-size marble statue of Handel was erected in London’s Vauxhall Gardens, an honour normally reserved for monarchs and the nobility. Despite his fame, the composer was at a crossroads in his career, moving away from Italian-style opera, whose star was waning with London audiences, and turning to the English oratorio. Handel wrote almost 30 oratorios in all – including Semele, Judas Maccabaeus, Theodora and Alexander’s Feast but, of the biblical works, only Israel in Egypt and Messiah take their texts directly from the scriptures rather than featuring rewritten prose or verse. For many years too – before the Handel revival of recent decades – Israel in Egypt was second only to Messiah in popularity.