What makes a good scientist?

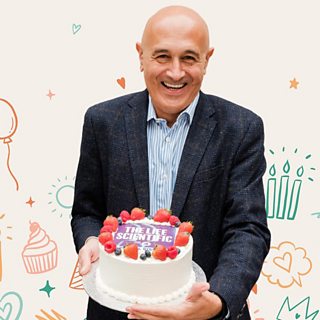

Over the last 10 years, physicist and broadcaster Jim Al-Khalili has interviewed nearly 250 people for The Life Scientific. To celebrate this milestone, Jim invited a panel of guests to get to grips with what makes a good scientist and what the pressing concerns of the scientific community are at the moment.

To dissect these issues and more, Jim spoke to: Professor Dame Ottoline Leyser, CEO of UK Research and Innovation; Nobel Prize-winning biologist and director of the Crick Institute, Professor Sir Paul Nurse; geologist and Royal Institution Christmas lecturer Professor Christopher Jackson; and forensic scientist and member of the House of Lords, Professor Sue Black. True to The Life Scientific’s track record, some answers may surprise you!

Is there a type?

Professor Dame Ottoline Leyser thinks that – potentially – anyone can be a scientist.

Science is really only about two questions, one of which is ‘how does it work?’ and the other is ‘how can I make it better?'Professor Dame Ottoline Leyser

“At its core, science is really only about two questions,” says Leyser, “one of which is ‘how does it work?’ and the other is ‘how can I make it better?’ You can ask those questions in either order, and some people prefer one to the other, but almost everybody asks themselves those questions at some point in their lives about something.”

Given that Jim’s guests over the years have included mountain climbers, dancers, activists, artists, a professional magician, a marketing executive and a linguist – all of whom have turned to science – it really does take all sorts.

You don’t necessarily need to be good at science

Drawing on his extensive interviews, Jim recalls Nobel prize-winning biologist John Gurdon came bottom of his year group in biology at school and was told it would be ridiculous for him to do A-level science, so he did classics!

Another example of someone who came to science later on in their studies is Professor of Earth Science, Sanjeev Gupta. Professor Gupta preferred history, describing science as not “particularly exciting” and that “there wasn't any mystery to it in the way that it was taught.”

Why getting things wrong is good for science

����ý Ideas explores why uncertainty makes scientific progress possible

A certain kind of observant

Science is a combination of being the artisan, doing something, watching something, observing something...and trying to make sense of it all.Paul Nurse

It goes without saying that a scientist should be observant. However, medical physiologist Frances Ashcroft, who discovered a highly effective treatment for a rare form of diabetes, pinpoints a particular kind of perception – the “ability to be able to pick the unusual thing out of the huge noise”.

Paul Nurse concurs: “Science is a combination of being the artisan, doing something, watching something, observing something, in addition to thinking and trying to make sense of it all.”

Ask why

Like being observant, curiosity is another given. Again, all of us start asking “why?” as children, but as Sue Black says, budding scientists “possibly get a little bit hooked.”

Giving an example of the common feature of “curiosity about the world”, Paul Nurse references biologist John Sulston who spent years cataloguing worm cells, an exercise that led to that mapped all of our genes!

There’s no need to be a nerd

Perseverance, tenacity and an unflappable attitude in the face of repetition also figure in the rundown of traits that a good scientist might have. What scientists don’t need to be, the panel agreed, are nerds.

“The kind of Big Bang Theory vision of what a scientist looks like probably could put science back decades,” says Christopher Jackson.

You don’t have to be Einstein either

Jackson has an equally forthright view about the idea that a scientist needs to be a “lone genius” as Einstein has been described (incorrectly so, some argue).

“The lone genius narrative makes me so cross because what it says is, unless you're the one considering the great big ideas and committing them to papers in certain journals, then your science isn't as valuable as the science of somebody else's. But we need a huge range of people to make science work.”

Be collaborative

The antithesis of the lone genius is the team, and the panellists all stressed the need for diversity of opinion and an interdisciplinary approach. Jim plays an excerpt from an interview with vaccinologist Dame Professor Sarah Gilbert, the driving force behind the Astra Zeneca vaccine, where she contrasts the two approaches:

I don't only want to study the world, I want to change the world.Peter Piot

“Discoveries are often made at the boundaries between disciplines, and, whereas there are some scientists who will happily work more or less on their own on one subject for a very long period of time and really do their own in-depth analysis of one thing, that's not the way I like to work. I like to try to take into account ideas with lots of different areas, technologies from different areas and bring it all together.”

Listen and engage

Interdisciplinary collaboration is crucial to discovery (Ottoline describes part of this as “the power of analogy, when a colleague can help crystallise what you’re thinking”), meanwhile communicating those discoveries means engaging with the wider public.

The nuances of scientific discoveries are sometimes buried in dense research papers, and there’s a popular belief that scientists tend to identify problems and not solutions. So, Jim asks if scientists should “get out more” – the general consensus is “yes”.

“There are very few people in the science professions who can't do something useful and valuable in a very broad box labelled ‘engagement’,” says Ottoline, “even if that's just going to the pub with their friends and listening to what they're saying.”

Speak truth to power

It’s not always the natural inclination of scientists to get involved in political decision-making. However, the Covid-19 pandemic brought the two worlds closer by necessity.

Many of those who have journeyed from the lab into the corridors of power are happy that they did.

One example is HIV epidemiologist Peter Piot, who took a sabbatical year with the World Health Organisation and went on to become executive director of UNAIDS: “Every year, there were millions more people who became infected, and I said, ‘how long can I study this unfolding disaster?’ I don't only want to study the world, I want to change the world.”

More science on Radio 4

-

![]()

The Life Scientific at 10: What makes a scientist?

Jim Al-Khalili and distinguished guests reflect on ten years of The Life Scientific.

-

![]()

The Patrick Vallance Interview

Jim Al-Khalili talks to the government's chief scientific advisor.

-

![]()

The Men in the White Coats

Prof Andrea Sella on the shifting image of the scientist in popular culture.

-

![]()

����ý Ideas: Day of the Scientist

Videos exploring the contribution of scientists to public life,