Should we stop having children?

The stats make for sobering reading: global population is set to hit 10 billion by the year 2050. Given the ever-increasing pressure on resources and the natural world, is it time to consider our personal responsibility when it comes to slowing the spread of humanity?

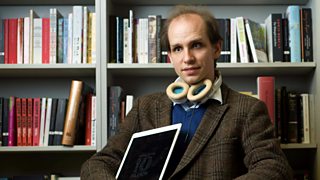

As prepares to debate the uncomfortable issues surrounding the fabled ‘population bomb’, moral philosopher Simon Beard considers both sides of this emotive debate.

My name is Simon and I’m a moral philosopher with a problem.

I’m a 32-year-old white male. I work in a university and live in the suburbs with a wife and two children. I choose not to eat meat or travel by aeroplane. I obey the law, pay my taxes, give money to charity and buy fair trade and organic where I can, and when I can afford it.

But by far the most significant of all of these things – from a moral perspective, at least – are my children.

I may try to reduce my ecological footprint, but my children will approximately double it. I may pride myself on being a conscientious citizen who contributes to the good of society, but by having children I impose obligations on other people to protect, educate and care for them. Having children has even altered my moral character and psychology – focusing my attention on the welfare of those closest to me and robbing me of the time and resources to help others who may be needier.

I love my children dearly, but are they the biggest moral mistake I ever made?

There’s no shortage of people who would argue that they are. Concern about overpopulation (both in the UK and globally) is widespread, with many people believing that remaining “childfree” is the most ethical thing to do.

Published in 1968, The Population Bomb predicted that population growth would inevitably produce social and ecological disasters, including world-wide famine and global war

Influential works like Paul R Ehrlich’s The Population Bomb, though written 50 years ago, still loom large in the public consciousness. A best-seller when it was published in 1968, The Population Bomb predicted that population growth would inevitably produce social and ecological disasters, including world-wide famine and global war.

It’s difficult to know whether predictions like these were ever seriously intended, but . Yes, the world’s population is twice what it was when The Population Bomb was written – but life expectancy is rising, and extreme poverty is in decline around the world. Some take this as proof that there isn’t a problem with population growth, or that it’s easily solved.

Others go further and argue that it would be better if there were even more people. The philosopher Toby Ord, for instance, argues not only that children’s lives are intrinsically valuable, but that , not just contribute to them.

In one sense, this is obviously correct. Overpopulation isn’t a problem because there are “too many people” – it’s a problem because there is “not enough planet”. If we had the resources to ensure a decent quality of life for all, then I think most people would agree that the more humans there are, the better. We are social creatures, after all.

Yet despite the progress we are making in dealing with global poverty and improving people’s quality of life, it is undeniable that the earth’s resources are finite. Moreover, humanity continues to store up ecological disasters – from climate change to plastic in our seas – that will haunt us for centuries. If we survive that long.

The future of our oceans

Sir David Attenborough gives his closing message for the Blue Planet II series.

Human beings are simply incredible at problem solving. And so far, we have managed to deal with the difficulties that living with a growing population throws at us (more or less). But do we have to make things so hard for ourselves? , our problems would surely be easier to solve if the world’s population was growing more slowly.

Personally, I am convinced that the truth lies somewhere between the poles of this divisive debate. Decisions about having children simply cannot be reduced to a simple mathematical calculation about population numbers: they also depend, crucially, on what we are willing to do to help future generations continue to flourish.

Deciding whether or not to have children will always be a deeply personal and private matter, but it raises important ethical questions for all of us.

What impact do our children have on others, and ourselves? How much should society support individuals who choose to have children? And will we ever conclude – as Paul R Ehrlich did in 1968 – that enough is enough?

Simon Beard is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Cambridge's and a member of .

-

![]()

The Population Bomb

Experts debate the bestselling book whose predictions influenced public policy... and didn't come true.

-

![]()

Radio 3 New Generation Thinker Simon Beard explores the existential risk and meanings of death.

-

![]()

Should we stop worrying about our growing global population and look forward to an age of abundance and prosperity?

-

![]()

Browse all the fascinating debates, talks and features from this year's festival.