Facing the storm: Filming the chameleon鈥檚 journey of a life-time

To film the story of the chameleon’s journey to find a mate, and ultimately lay her eggs, the Big Little Journeys team travelled to the most remote filming location of the series – Kirindy Forest, in western Madagascar. Here, Producer Valeria Fabbri-Kennedy reveals what it took to film the chameleon's journey.

The chameleon’s journey is extremely short from a human perspective and their lives are only a few months long, programmed to expire before the dry season arrives. So, we only had a short filming window to capture the whole story. This included travelling, and filming, in the middle of cyclone season.

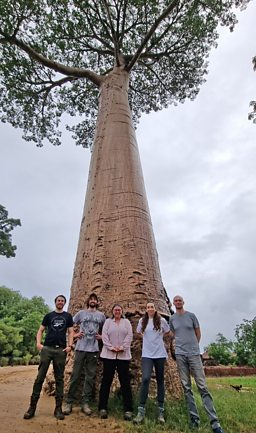

Upon arriving in Madagascar, at the tail end of Tropical Storm Cheneso, we found the high winds and torrential rains had destroyed roads and bridges. During the two-day drive to Kirindy, a blown down tree blocked our way and had to be cut into pieces with a hand axe, and dirt tracks had become muddy rivers, as high as the bonnets of the trucks. It took 13 hours to reach camp, only to find that the electricity wasn’t working. But, after a few days, the storm finally passed and we were able to begin filming the chameleon’s journey.

In order to tell the full story, we had to film several individuals at different life stages and, to find them, we needed the help of a team of local scientists. This included Ludo Mitchel Raoelina, a PhD student from the University of Mahajanga working alongside Dr Christopher Raxworthy, from the American Museum of Natural History, who has been monitoring these chameleons for decades.

During the shoot, we faced constant electricity outages, meaning that we couldn’t charge our batteries or download footage, and flooded roads stopped supplies coming in, resulting in only chips for lunch, every day! Frequent flash floods sent ants, rats, and various exotic insects into our sleeping quarters and we scrambled to keep the equipment safe and dry during sudden downpours, whilst getting drenched to the skin. Most of us also suffered bad sickness. Despite the challenges, we successfully managed to capture many never-before-filmed elements of the chameleon’s behaviour.

These reptiles are tiny, but every step of their journey is full of herculean challenges. They climb trees - the equivalent of a human scaling the empire state building! They face giant snakes large enough to swallow them whole, and the females must defend a territory within which they can display their colours and attract a mate, before time runs out. Every obstacle wastes precious time and could prevent them from laying their eggs before they die, and one of the biggest impacts on their world is caused by humans. In the film, we show how our hero’s efforts come to nothing, when she finds that she has climbed a stump and is at the very edge of the forest – where once there were trees all the way to the horizon, now there is nothing - her only chance is to turn around and go back the way she came. Over half of Madagascar’s forests have been cut down but as Chris Raxworthy says, “the great news now is that there is a lot more forest that is protected within reserves” and Kirindy is one such area.

Every year a generation of female chameleons complete journeys, to find a mate, and ultimately to lay their eggs, just in time before they all die en-masse, along with the males. For six months of the year, through the harsh dry season, all that remains of this ephemeral species, are thousands of eggs beneath the soil. Time capsules that are specially evolved to wait until the rains return before they hatch, and a whole new generation emerges. However, “it seems like a very risky strategy to put all of your eggs in one basket, they have no back up generations to keep the population going” says Chris Raxworthy, because with their lives so intimately in-sync with the seasons, a shift in the climate, and the timing of the seasons, could be devastating. What makes this more poignant, is that we managed to capture something that no-one has ever seen before. Chris recognised the signs of a female beginning to die, and so our camera operators set up timelapse cameras to film it.

Spending time filming these amazing tiny reptiles, it鈥檚 impossible not to fall in love with them.Producer, Valeria Fabbri-Kennedy

When we returned several hours later, the scientists were amazed – the sped-up footage revealed that as the chameleon dies, colours cascade across its skin like fireworks erupting all over it’s body. As chameleons change colour for communication, it can be described as being like the female’s last words. Spending time filming these amazing tiny reptiles, it’s impossible not to fall in love with them. None of us were prepared for what we witnessed, when we filmed the female dying. Watching her life fade away like that, in such a stunningly beautiful way, was really emotional. I don’t mind admitting it moved me to tears and affected me for quite some time.

Just as we were filming the final pieces of the story, we received news that a Category 5 Tropical Cyclone, named Freddy, was about to hit the east coast – on course for Kirindy. With winds of 160 mph, it was too dangerous to continue and so we scrambled to get the final shots, before evacuating. Freddy became the longest-lived and most energetic tropical cyclone ever recorded. It crossed the entire southern Indian Ocean, from Australia to Mozambique, and lasted over 5 weeks. Not only is the chameleon's life-cycle at risk from climate change but destructive cyclones like this could also become more common, as it's believed they are increasing in intensity and slowing down.