The real Van Gogh: A genius not driven by madness but crippled by it

14 July 2016

Vincent van Gogh is the original tortured artist. The famous severed ear, the suicide by gunshot, and the vast body of work 'discovered' after his death - all shorthand for a genius cruelly ignored and a mind that was tragically unsound. , a new exhibition at Amsterdam's Van Gogh Museum, tackles these preconceptions head on. As WILLIAM COOK finds out, the truth about Van Gogh's creativity and mental health is far more complex - and richer - than simple headlines.

Was Van Gogh really mad? Did his madness drive his art? And did he really ? These are the key questions in at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam. And the answers are: yes (sometimes); no (not really) and yes (well, almost).

did suffer from periods of insanity, but most of the time he was sane and lucid. He worked non-stop between his breakdowns, but when he was in the midst of madness he was unable to paint at all. He did indeed cut off his ear (his whole ear, not just the earlobe) and gave it to a woman in a brothel, but she wasn’t actually a prostitute – she only worked there as a maid.

Van Gogh’s insanity is central to his biography, but this is the first time the Van Gogh Museum has made it the focus of an entire show

These revelations are the result of seven years’ research by Bernadette Murphy, author of a new book called Van Gogh’s Ear – The True Story, but there’s more to this absorbing show than the tale of Vincent’s ear.

Van Gogh’s insanity is central to his biography, but this is the first time the Van Gogh Museum has made it the focus of an entire show. The result sheds fresh light on Vincent’s psyche, and its effect upon his art.

Vincent cursed the bouts of madness which stopped him painting, but he also wondered if these fits, though debilitating, might be linked in some way to his creativity. Gazing at these vivid pictures, you end up wondering the same thing.

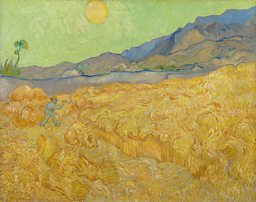

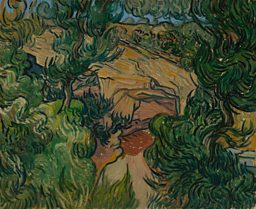

This show traces the final chapter of Vincent’s life, from his arrival in Arles in 1888 to his suicide two years later. This was his most troubled, and yet his most productive period. In Arles he painted a host of brilliant pictures, of electric intensity, but after came to live with him he went off the rails. On 23rd December 1888 he sliced through his left ear with a razor and delivered it to a local brothel, where he’d been a frequent customer.

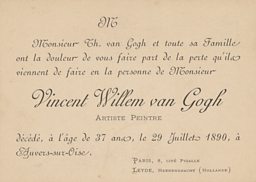

After a spell in hospital, he was confined to a lunatic asylum. For the next 18 months he was in and out of asylums, lurching between crippling mania and frantic productivity, until he shot himself, aged 37, in Auvers-sur-Oise.

On The Verge of Insanity guides us through these last two years, using documents and artefacts as well as paintings to tell the story. The pistol he (probably) used to kill himself is here, as is the petition which his French neighbours signed to complain about his increasingly erratic behaviour.

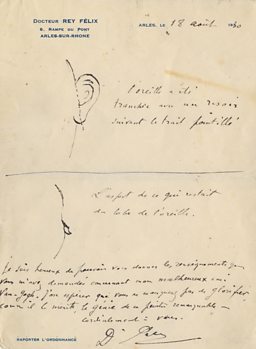

The most thrilling document is an illustrated memo from Felix Rey... It shows he’d severed his entire ear - rather than just the lobe

The most thrilling document is an illustrated memo from Felix Rey, the doctor who treated Vincent after he cut off his ear.

It shows he’d severed his entire ear - rather than just the lobe, as Vincent’s friends later claimed.

This memo was hidden away in the files of Irving Stone, the American author of Lust For Life, a novel about Van Gogh which inspired .

Stone happily admitted his book was fictionalised, so even though it did a great deal to popularise Van Gogh, it’s never been taken seriously as a historical source. However Stone had been to France to research the book, and he’d tracked down Dr Rey. It took Bernadette Murphy, a first time author, to find this document, and realise its significance.

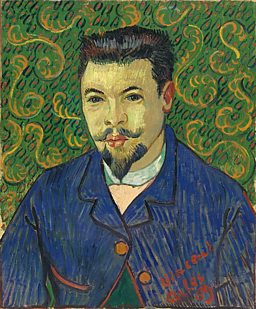

Murphy’s scoops are intriguing, but the greatest treasures are the paintings. Most are from the Van Gogh Museum’s permanent collection (the biggest Van Gogh collection in the world) but there are loans from other galleries, most notably his portrait of Dr Rey, now in Moscow’s Pushkin Museum (Van Gogh gave this portrait to Rey - ‘a really good fellow’ – as a thank you present. After he died Rey sold it, for a relatively modest fee).

So what does this show tell us about Van Gogh’s mental health?

There are no conclusive answers - opinion has shifted with the fashion of the times. At the time he was diagnosed as epileptic, put in solitary confinement, and treated with a succession of hot and cold baths.

Since then he’s been called bipolar, psychotic, even schizophrenic. Today, manic depressive seems closest to the mark. In all likelihood, Van Gogh’s insanity was the result of several factors: there was some history of madness in the family; he’d been unstable from an early age; syphilis may have played a part (his brother Theo died of syphilis six months later) and his heavy drinking didn’t help…

The exhibition refutes some stubborn myths: no, Gauguin didn’t cut off Van Gogh’s ear (although Van Gogh may well have threatened to kill Gauguin); no, Van Gogh wasn’t murdered by a bunch of local schoolboys - as he said on his deathbed, if this suicide attempt had failed he simply would have tried again.

He crammed more into a decade than most artists manage in a lifetime, including 75 paintings in his last 70 days

This dying testimony answers the biggest riddle of Van Gogh’s truncated life: was his suicide inevitable? Sadly, the answer, it seems, is yes. And yet a few weeks before his death he told Theo, ‘I still love art and life very much indeed.’

Inevitably, it’s tempting to wonder what more he might have achieved. He’d only sold a handful of paintings, but the word about him was spreading. Imagine what masterpieces he could have painted if he’d lived another 37 years?

Yet he crammed more into a decade than most artists manage in a lifetime, including 75 paintings in his last 70 days. Rather than rueing what might have been, we should be thankful he achieved so much in such a short time.

‘A lot of people think his art was a product of his illness,’ says the show’s curator, Nienke Bakker. ‘He painted in spite of his illness.’

Of course she’s quite right. Vincent’s illness wasn’t the cause of his artistic genius, any more than George Best’s boozing caused his balletic genius with a football.

And yet, like Best, or any number of self-destructive virtuosos, it’s impossible to imagine the man without his demons. Madness was no help at all (in fact, it was an awful hindrance) but this fine exhibition merely reconfirms, despite its best efforts to the contrary, that Van Gogh’s insanity was inseparable from his art.

is at the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam from 15 July to 25 September 2016.

More van Gogh on the ����ý

-

![]()

6 August | ����ý Two

-

![]()

Book of the Week | ����ý Radio 4

-

![]()

����ý News

-

![]()

����ý Archives

Impressionism on ����ý Arts

More from ����ý Arts

-

![]()

Picasso’s ex-factor

Who are the six women who shaped his life and work?

-

![]()

Quiz: Picasso or pixel?

Can you separate the AI fakes from genuine paintings by Pablo Picasso?

-

![]()

Frida: Fiery, fierce and passionate

The extraordinary life of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, in her own words

-

![]()

Proms 2023: The best bits

From Yuja Wang to Northern Soul, handpicked stand-out moments from this year's Proms